Note: This installment of Tough Guys, Gangsters, and Delinquents in Asian Pop Culture is a continuation of sorts of the post on Rookies and the trope of teachers redeeming delinquents. Huge spoilers below, and also, the manga pages below are read from right to left in the civilized manner. Great Teacher Onizuka and Gokusen scanlations thanks to Mangakakalot.

We all know about the Reformed Gangster, the individual who has washed their hands of the criminal life and more often than not, has also embraced spirituality and goes around teaching kids not to follow their path.

Redemption stories like these are really appealing, especially if they’re coupled with some kind of community service. First, it feels like justice: this person spent years terrorizing the community and causing destruction, now they can pay it back by preventing others from doing the same. It also smooths over the dangerous allure of the delinquent or gangster with the knowledge that they’re safe or “reformed”, kind of like a Goldilocks scenario: not too dangerous, not too safe, just right.

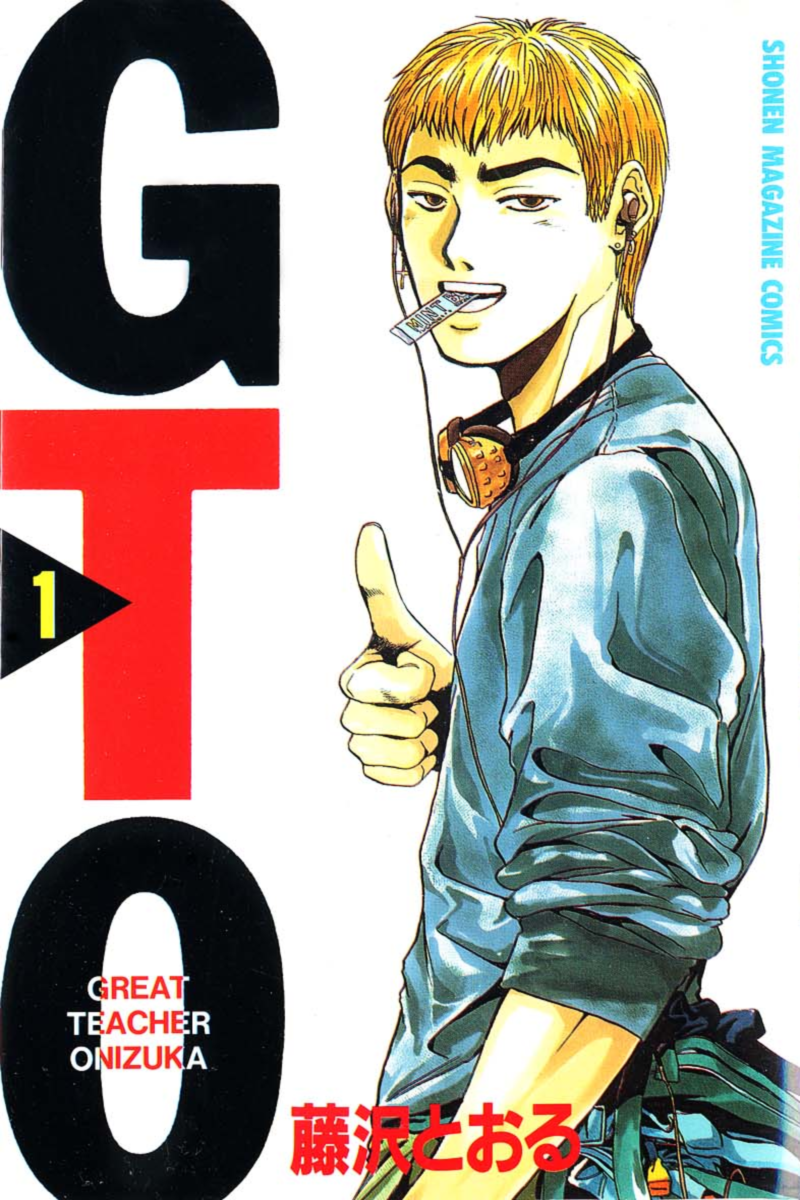

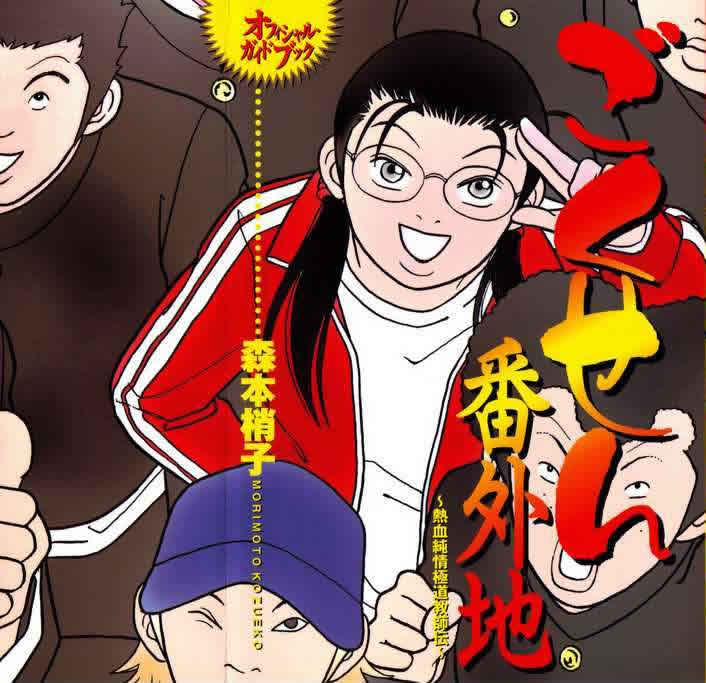

Great Teacher Onizuka (GTO) by Fujisawa Tohru is vaguely based on the Reformed Gangster trope in that Onizuka Eikichi (he’s rarely called Eikichi, so I’ll call him Onizuka) in GTO is a former biker gang leader with a rap sheet (some readers may remember him from the original bosozoku manga Shōnan Jun’ai Gumi! that Tohru wrote featuring Onizuka and his bike gang buddies. Yamaguchi Kumiko (to whom I’ll refer by her nickname, Yankumi) in Gokusen by Morimoto Kozueko, on the other hand is a yakuza heiress raised by her grandfather after the deaths of her parents at a young age.

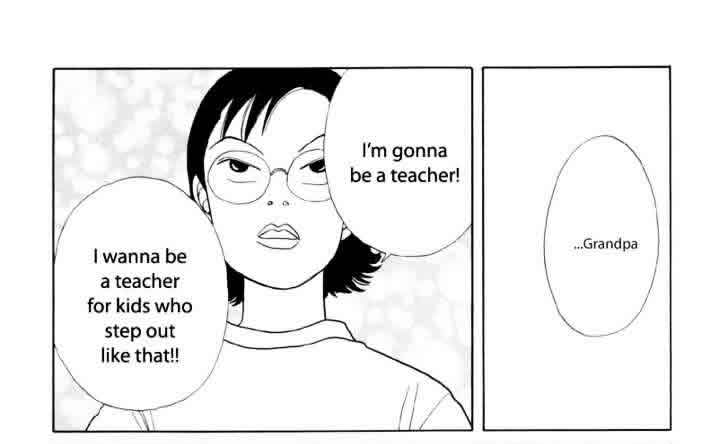

While Yankumi does have elements of the Noble Teacher like Rookies‘ Teacher Kawato and has always dreamed of becoming a teacher, Onizuka stumbles on teaching originally so that he could date high school girls (although the running gag of the manga is that he remains a virgin throughout, defusing his horniness and making him not only less creepy and gross but also more relatable to boys who are sexually frustrated themselves).

Although Yankumi and Onizuka are like the Reformed Gangster in their backgrounds and experiences, they diverge from this trope in a really important way: neither of them have renounced being a yakuza or delinquent. It’s a choice that not only adds to the comedy factor, but also addresses a minor paradox in the whole concept of Reformed Gangsters, who get their authority and wisdom from their past experiences as an outlaw but they go around telling people not to be like them.

Instead of being good teachers because they’ve learned from their past mistakes, Yankumi and Onizuka are excellent teachers exactly because they have found the positive side of being a yakuza or a delinquent, and it’s their acceptance of their true selves that get them the respect of their students.

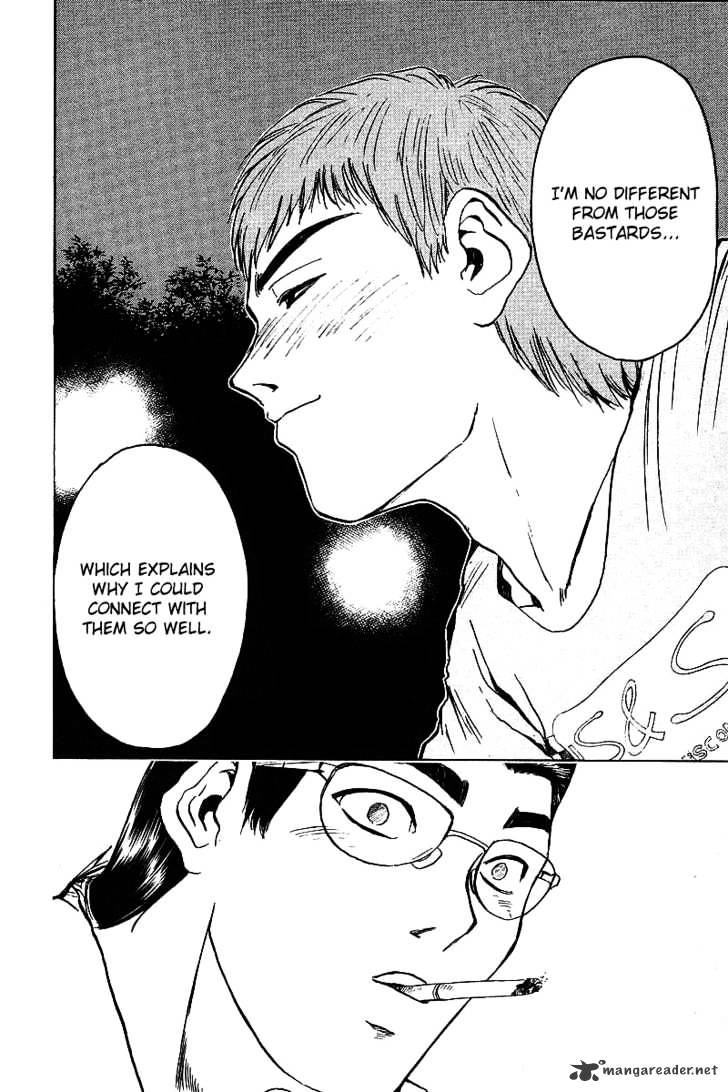

Also, by having the teachers be delinquents or yakuza themselves, Gokusen and GTO parody the Noble Teacher trope, but not just for comedy purposes but also as a way to provide social commentary. Although both Yankumi and Onizuka have the same belief in their students and the sense of honour that Noble Teachers have, it’s actually their own delinquent lifestyles that give them real insight into their students, kind of a “real recognize real” scenario.

Yankumi and Onizuka often battle symbols of the system like police, politicians, and school administrators, standing as a critique of how society treats children and how the education system (and the system in general) fails them. Their presence exposes the hypocrisy of the so-called upstanding adults around them: in GTO, Onizuka may be a horndog who loves porn, but he’s much less disgusting and perverted than adults who pretend that they’re morally superior to everyone else, like the principal Uchiyamada, who molests women on the train, and his fellow teacher Sugiwara, who is a pedophilic peeping tom. At the very least, he’s not a hypocrite.

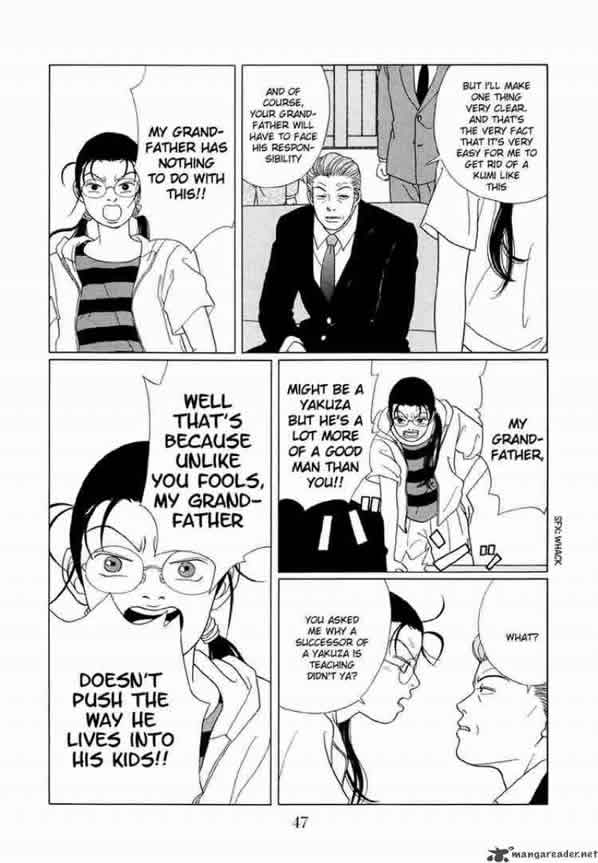

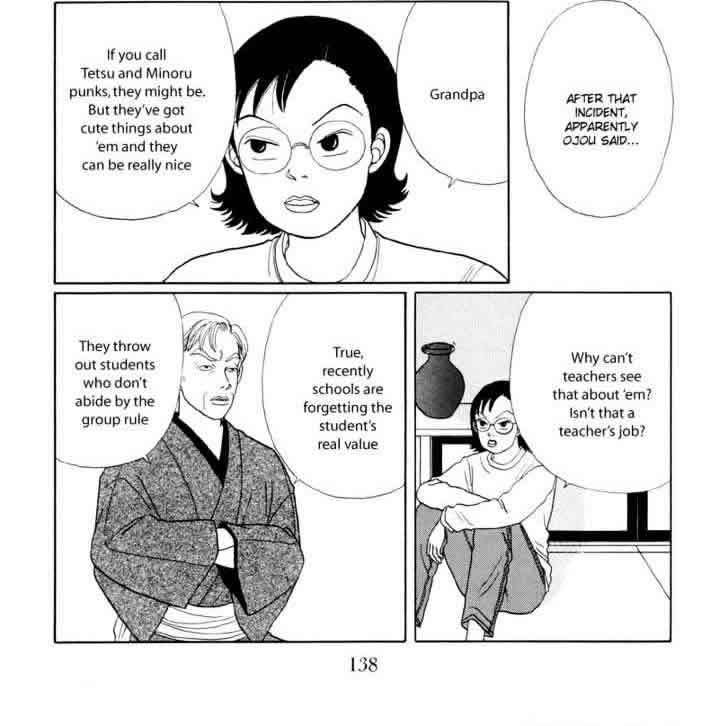

In Gokusen, Yankumi is rough and kind of violent, but she is extremely kind and honourable in contrast to “respectable” adults. Her “brothers” Tetsu and Minoru are abandoned by their parents and treated terribly by their schoolteacher. Her student Sawada Shin’s father is the head of the police and cares mostly about how his reputation and status. Her family, despite their liminal status in Japanese society as yakuza, behaves with more integrity and compassion.

Her family is also beloved by the community and only deals with vice, racketeering, and gambling. (I should mention here that as lovable and hilarious as Yankumi’s family is, after writing about Election, it’s a little odd to see the yakuza portrayed so benignly.) It’s also worth noting that these are Onizuka’s “sins”, too. For those who aren’t too familiar with East Asian cultures, this may be a good time to let you know that it’s considered less shady to be involved with vice, racketeering, and gambling compared to drugs and gun violence.

The big stigma against drugs in Asia can possibly be traced to three major wars that created a Western-backed drug trade: the Opium War, the Korean War, and the Vietnam War. The Opium War is probably one of the reasons that East Asian cultures are so anti-drugs; they saw how addiction crippled China, weakening it to the point of helplessness and leaving it vulnerable to plunder and invasion. The modern equivalent would be the opioid crisis in the US affecting the country so much that the entire infrastructure and government and military just falls apart so much that even Canada could march in and take away stuff like the Statue of Liberty (not that Canadians would want it, it’s not like it’s the Stanley Cup or something important).

As for Southeast Asian nations, in 1949, generals from the Kuomintang, who lost against the Communists in China, retreated to Burma and became opium farmers and warlords. When China joined the Korean War, the CIA and US government stepped in to support and arm the warlords in exchange for intelligence against China. This was the seeds of the Golden Triangle, and the eventual spread of drugs throughout Southeast Asia. The drug trade and the gangsters and warlords who terrorized local populations continued to be supported by the CIA and the US government through the Vietnam War, and is still probably supported by the CIA to this day.

The destructive effects of the Golden Triangle can’t be emphasized enough: the drug trade fuels corruption, human trafficking, homicides, and all types of crime, contributing to the continuing Third Worldism of developing countries. This is why people in Southeast Asia will support draconian government measures against drug addiction, even though quite frequently, these measures are kind of pointless and are often just covers for corruption and abuse of power.

While it’s true that triads and yakuza are a big part of the drug trade, to keep protagonists sympathetic, writers will often make them anti-drug, unless the stories are meant to be as close to real as possible like Election.

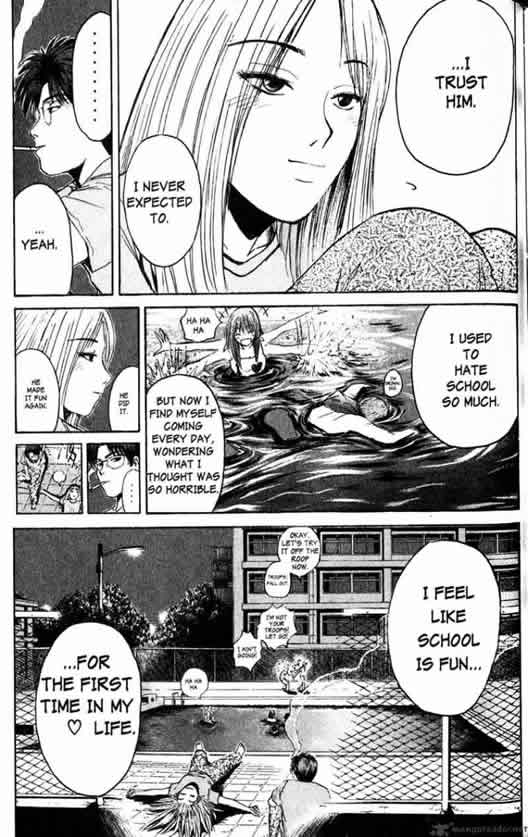

To go back to Gokusen and GTO, Yankumi and Onizuka are sillier and less realistic than noble Teacher Kawato in Rookies; they have almost superhuman strength, fighting ability, and healing power. However, like Teacher Kawato, Yankumi and Onizuka are the ultimate cool teachers who listen to the students, understand what is important to them, have a sense of humour and adventure, and most importantly, value the students as people.

They don’t expect their students to conform to society in order to succeed–why would they, when they themselves don’t? Instead, they believe in the students being their best selves simply by being true to who they are.

These manga naturally end up presenting the education system as a reflection of mainstream society, which prioritizes materialism and status over family and friendships. Both manga imply that the reason kids become delinquents is that adults have chosen their own selfish pursuits over their students and children, who are abandoned, disappointed, abused, and betrayed.

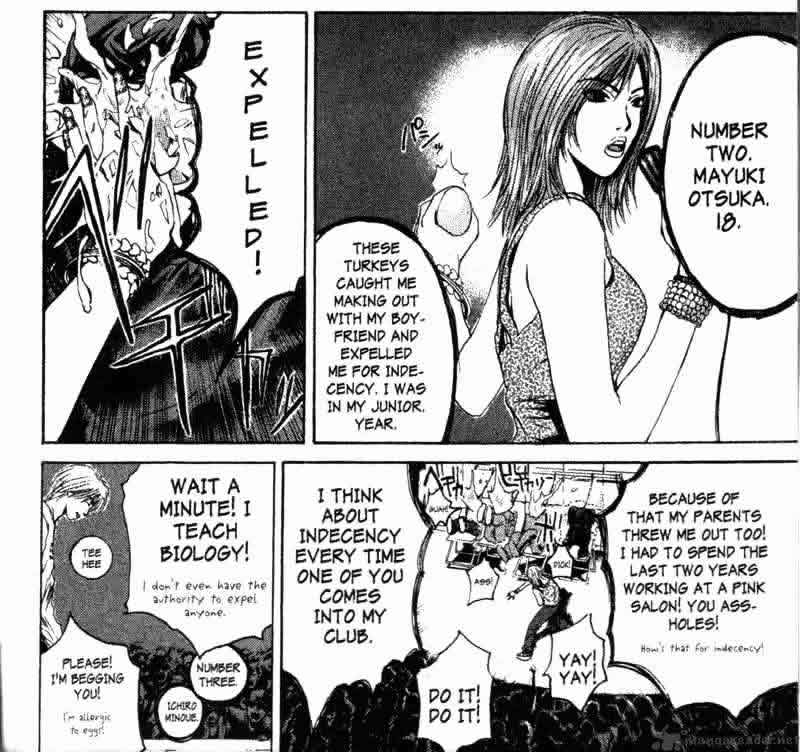

GTO in particular confirms everything that kids believe about adults, especially their unbearable (to a teenager) hypocrisy. There’s a chapter where a bunch of teachers have been tricked into attending a party where they have to face the wrath of the students they expelled for things that the adults are themselves guilty of.

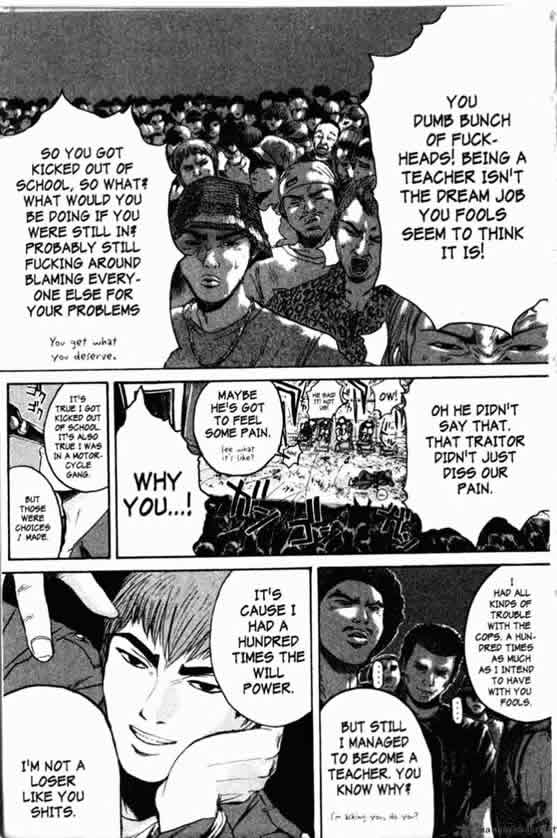

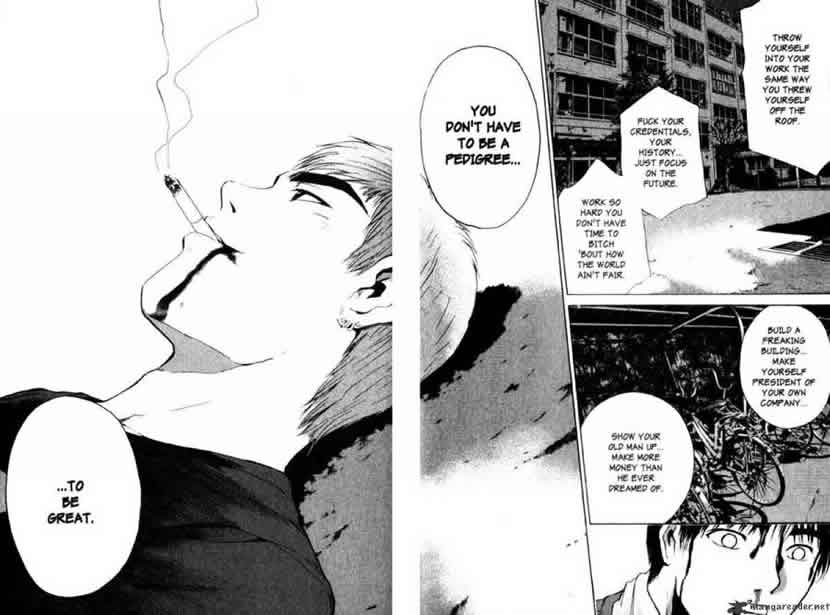

It’s a melodramatic “adults are phoneys” Catcher in the Rye situation that teenagers love, but at the same time, GTO never lets anyone off the hook for what’s happened to them in the past. As horrible and terrible your past may be, GTO doesn’t encourage the feeling of victimization. You may have been victimized, but you’re not a victim. You’re not forever tarnished by what’s happened to you, nor is it an excuse to be an asshole. As Gavin de Becker wrote in Gift of Fear, a terrible childhood may be an explanation, but it’s not an excuse.

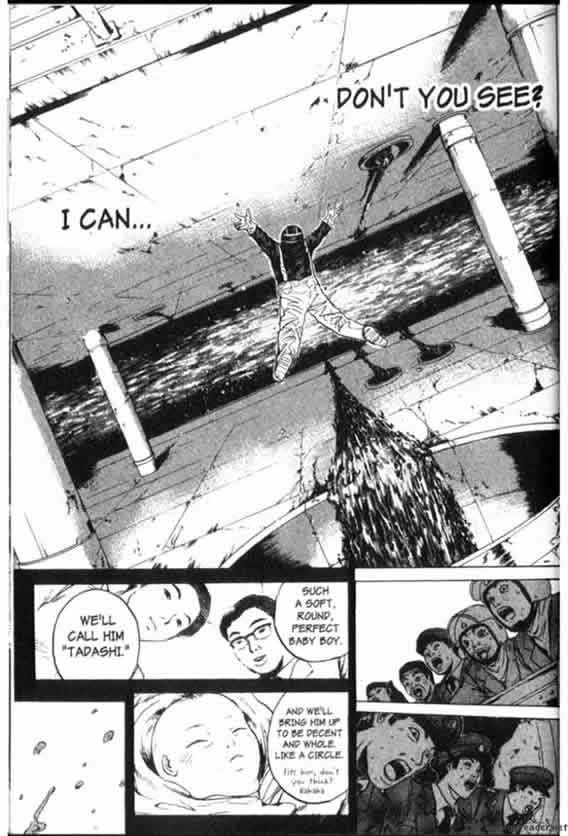

Conversely, even the worst adults were all once innocent babies and children full of hope, and although neither Gokusen nor GTO spends too much time on that, they do obliquely bring up questions about how society corrupts innocents and enables depravity. I must say, as a parent, this particular panel really affected me.

As I’ve discussed over and over, there are a lot of social and class critique in delinquent stories, and in Gokusen and GTO, the same themes appear: wealth, status, and power don’t make you happy. Nor does all the striving for top grades, top jobs, and top status make you a decent person. In fact, the biggest failures in the stories are the most superficially successful ones.

The questions about masculinity and what it means to be a man appear that permeate delinquent stories also appear in Gokusen and GTO, which leads me to wonder: why do boys need to learn how to be a man? Not just “why” as in “why do they need to” but also “why” as in: does that mean being a man isn’t biologically determined? Is it just a choice to be a man, then? What does it say about learning to be a woman?

It’s fascinating to think of that, especially in light of Yankumi’s character. She’s very butch but everyone just kind of shrugs and accepts she’s basically a man in all but physical body. Yankumi never really goes through a makeover, unless it’s to look like a stereotypical yakuza ane-san.

Throughout, she stays the same honourable Yankumi, with the same combination of toughness and naivete that we usually see in male characters like Monkey D. Luffy in One Piece or Oga Tatsumi in Beelzebub. And this doesn’t stop Shin (and at least a couple of other men) from falling in love with her. Although Gokusen is still mostly focussed on stories with boys, as Yankumi teaches at an all-boys’ school, it’s still anchored by her strength and her fearlessness, and the story never condescends to her, even when she’s a child.

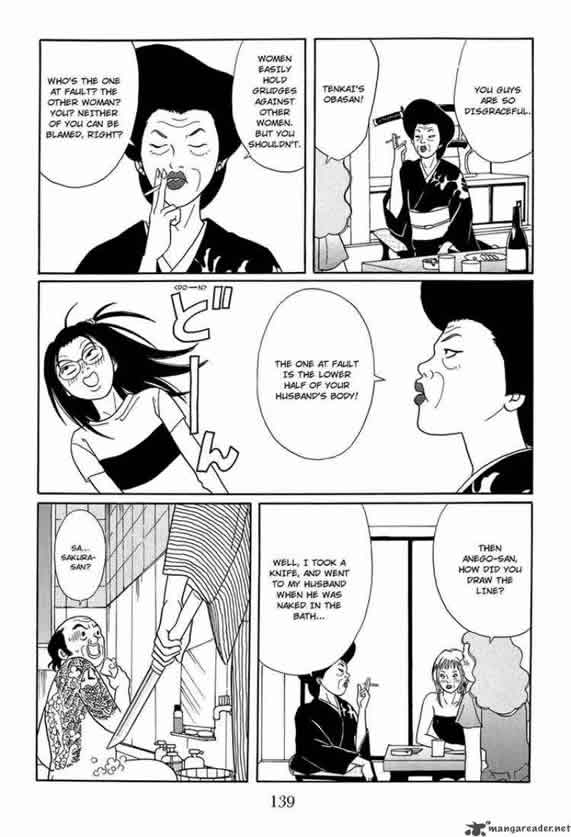

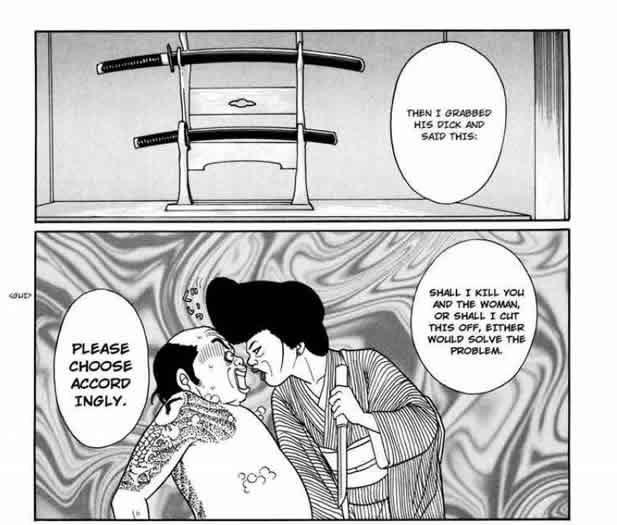

The women who live in the yakuza world also get a chance to tell their stories, which we hardly ever see or hear about in gangster stories, and it’s easy to sympathize with these characters even as you laugh.

GTO, on the other hand, is set in a co-ed school, and in contrast to almost every other delinquent story out there, many of the main student delinquents are girls. I’m very ambivalent about the depiction of girls and women in GTO. I understand that shounen manga practically requires panty shots and cleavage to draw in and titillate a young male audience. In fact, I can’t think of a single shounen manga that doesn’t feature at least one panty shot (Gokusen has them, too, in case you were wondering). But GTO uses it in such excess that it almost feels as though the manga is mocking it. If that’s the case, though, it’s a “trying to have their cake and eat it too” situation.

And yet, at the same time, the girls and women in GTO are characters who have as much humanity, intelligence, courage, and value as the boys and men, and it’s their stories in GTO that are the most compelling. It’s so rare to get stories of female delinquents, and in a lot of ways, GTO doesn’t disappoint. They fight back against perverts and rapists; they protect each other; and they are resourceful villains and heroines on their own. I get that teenaged girls (and even older women) act out sexually for a variety of reasons, so I’m not saying that it is unrealistic to see it in GTO, but it’s only the girls that are sexualized and objectified like that, and it cheapens their otherwise great characterization.

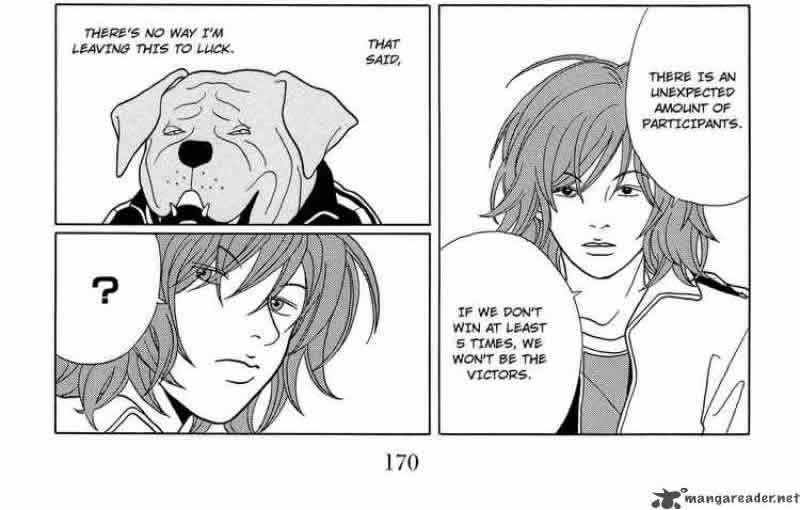

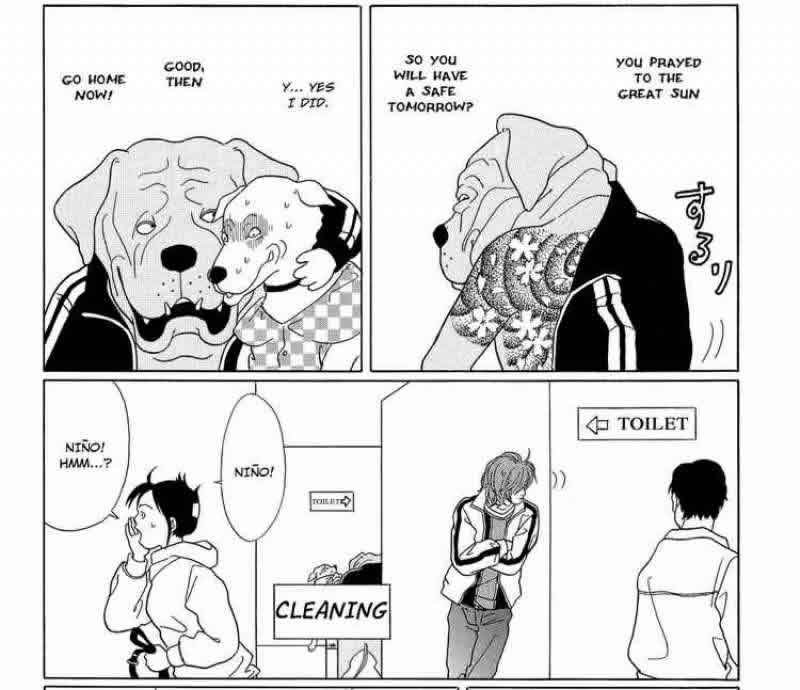

Gokusen is a lot simpler than GTO because it is basically a gag manga. There are entire sections devoted to Yankumi’s adidas-wearing dog, Fuji, and his attempts to corral Shin into doing shady stuff with him, like trying to win a dog competition by using yakuza intimidation tactics, and they are just hilarious.

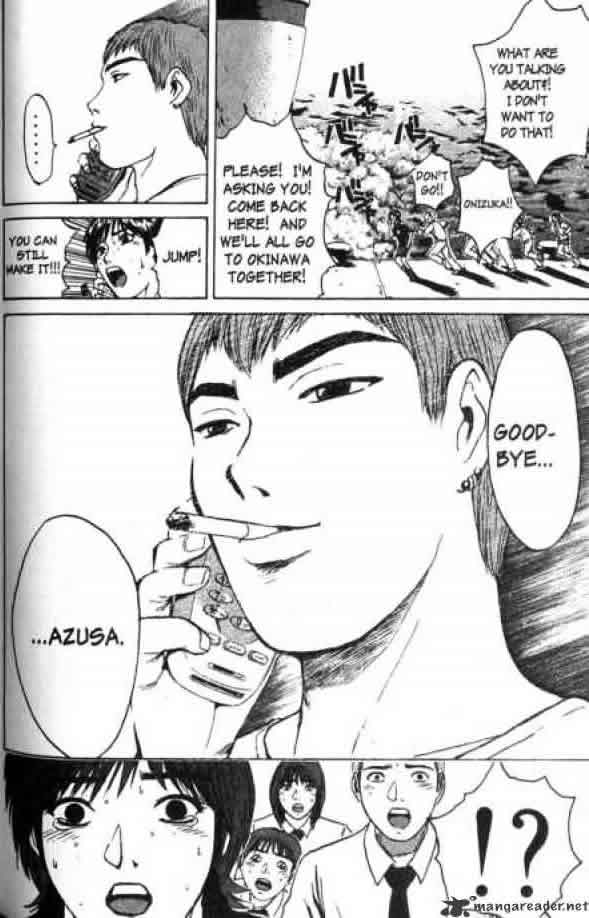

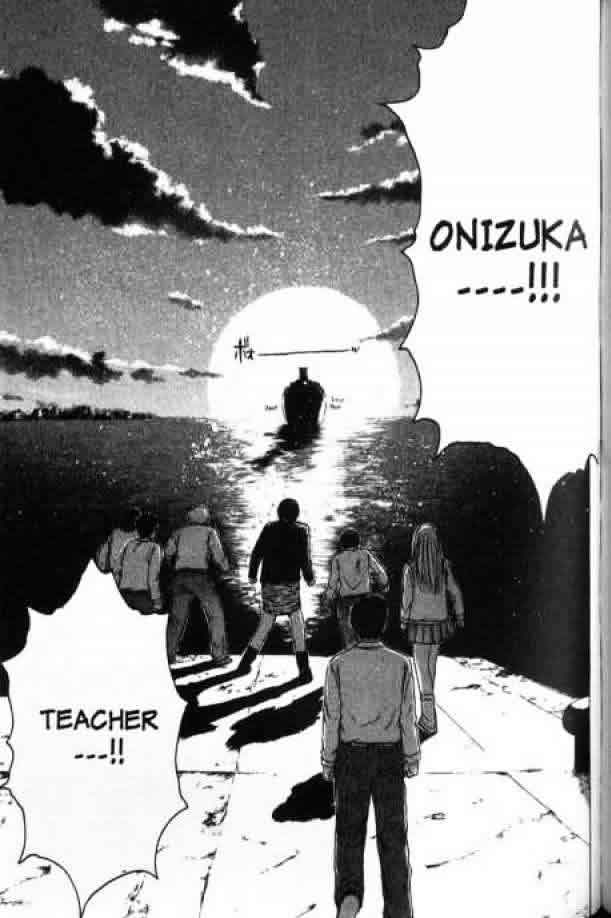

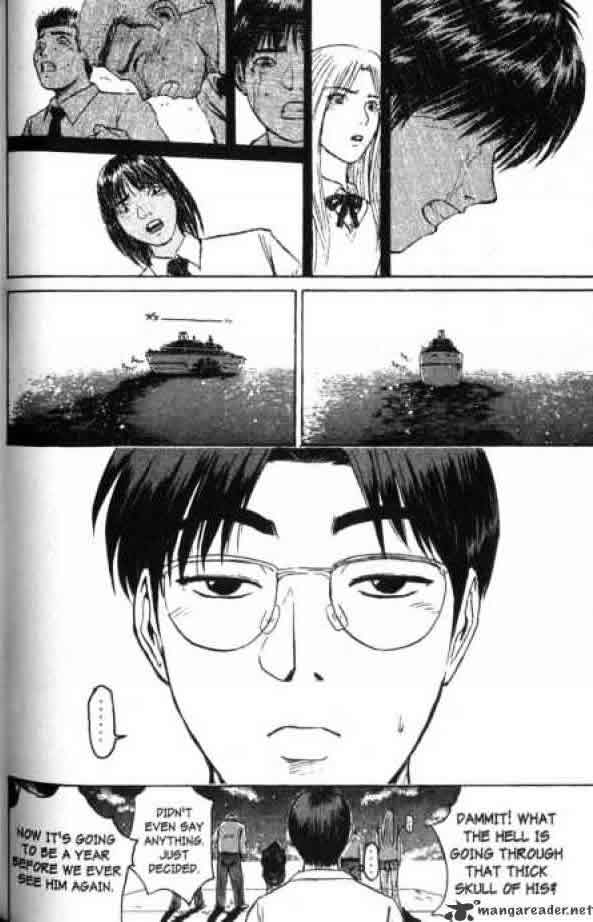

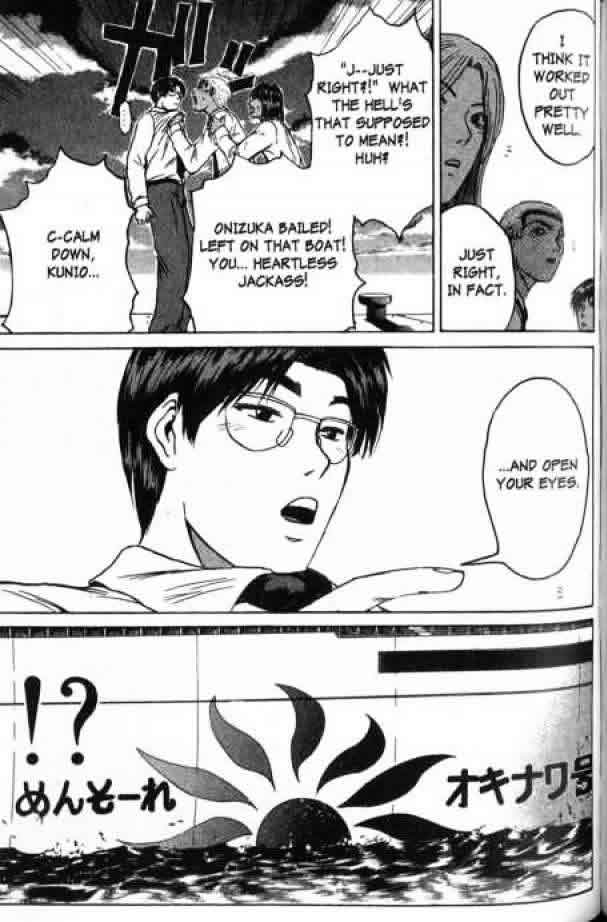

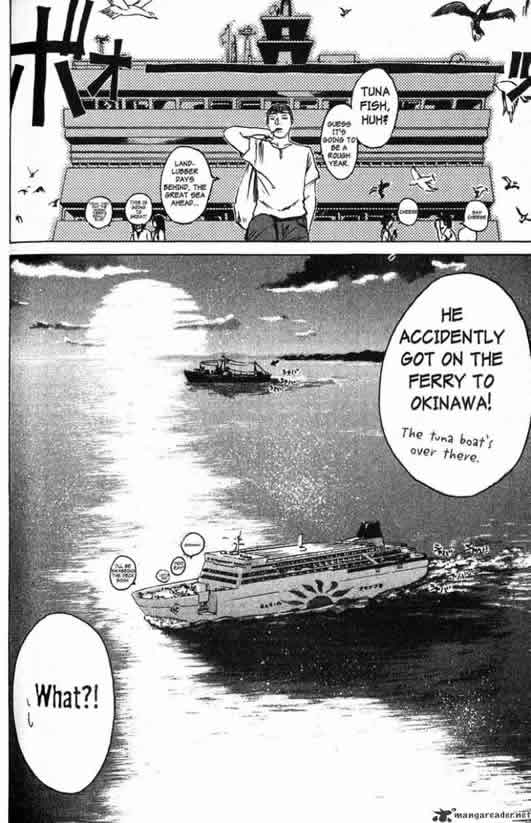

That’s not to say GTO isn’t fun either; dramatic and tense scenes are often undercut with a hilarious sense of self-deprecation, and no one is allowed to become too heroic or superior, like in this scene where Onizuka has made a huge sacrifice in quitting his job, giving all his money so that his students can go to Okinawa on a field trip, and going off himself to work on a tuna boat for a year, only for his students to realize that dumbass Onizuka got on the wrong boat.

I’m going to end by saying that I think that the main reason that delinquent stories are so popular is that they have a core of compassion that no amount of gags and panty-flashing can hide. They are all about acknowledging the value and beauty of people whom society deems as trash, and they tell us that each one of us is worthy of love and respect.

For any sad, bullied, or insecure kid out there–and most of us have been at least one of those–it’s a comforting thought to have.

If you liked this post, you might like my fiction too! I am writing a fun neo-wuxia trilogy about an alternate-reality Hong Kong where there are martial arts societies who haven’t modernized and live side-by-side with contemporary Chinese cities. You can sign up for my mailing list to get a preview when it’s done.

I’m also halfway through my Ming dynasty X-Files book, and I’m pretty sure I’ll be done by February 2021. So if you want to get a preview of a jinyiwei (imperial military police) with a kill list teaming up with a pretty-boy aristocrat to track down UFOs, ghosts, monsters, and other supernatural phenomena in your inbox, sign up below too!