Note: For this Tough Guys, Gangsters, and Delinquents in Asian Pop Culture entry, I’m looking at Morita Masanori’s manga Rookies as part of an exploration into the “redeemed by teacher” trope in delinquent stories. As usual, spoilers everywhere.

Scanlations by Losers at Mangakakalot

Scanlations by Losers at Mangakakalot

The appeal of delinquent and gangster stories is mostly founded in wish fulfillment. Delinquents and gangsters have the freedom to do whatever they want without having to worry about petty daily concerns, they aren’t beholden to laws and can just fight or kill people who get in their way. There’s something about that simplicity that probably triggers some kind of residual attachment we have to honour culture.

When you consider that most delinquent stories are about glorying in the life of a delinquent–a life that is freer and more exciting (and violent, but that’s part of the fun) than the life of a miserable cog in the capitalist machine–it may be a little strange when you consider how popular the theme of teachers redeeming delinquents is.

If it’s so great to be a delinquent, there should be no need for To Sir, with Love stories, where a teacher comes in to make the delinquents’ lives better and reform them. But the popularity of this trope reveals something really important lurking under each delinquent story: being a delinquent is an unsustainable lifestyle that must eventually bow to mainstream culture and values.

All of the stories I’ve looked at for this series tackle the idea of fitting in with mainstream society with the conclusion that delinquents and gangsters will be marginalized whether or not they try to fit in. High-spirited delinquent teenagers grow up to either become gangsters who have to resign themselves to a violent death or people who compromise their spirit for a life as a working class drone (with the exception of a few lucky ones). Gangsters who seek to redeem themselves and reintegrate in mainstream society are either driven back to a criminal lifestyle or unable to feel redemption. It’s all pretty grim for everyone except for tough guys of justice like Ting in Ong Bak.

Thus, redemption via teacher is a way to still be able to tell a delinquent story but have a less depressing ending (or, like in Crows, an ambivalent ending). Besides, the delinquent redeemed by a teacher stories are also a type of wish fulfillment narrative: that these scary and mean delinquents are really softies at heart who just need someone to believe in them.

The misunderstood anti-hero who can be redeemed by love is a hugely attractive type, with fans either relating to the hero because they see themselves as misunderstood too or wanting to redeem the heroes because they have a tendency to fall for codependent relationships. (No judgment here, by the way. I too have been on both sides.) But underneath it all is a kind of drive to normalize and assimilate those who don’t quite fit in.

I’ve always found it fascinating that we love delinquents and gangsters for being wild rule-breakers, but then we also love redeeming them and thus negating everything that made them so cool to us in the first place. It’s strange, isn’t it?

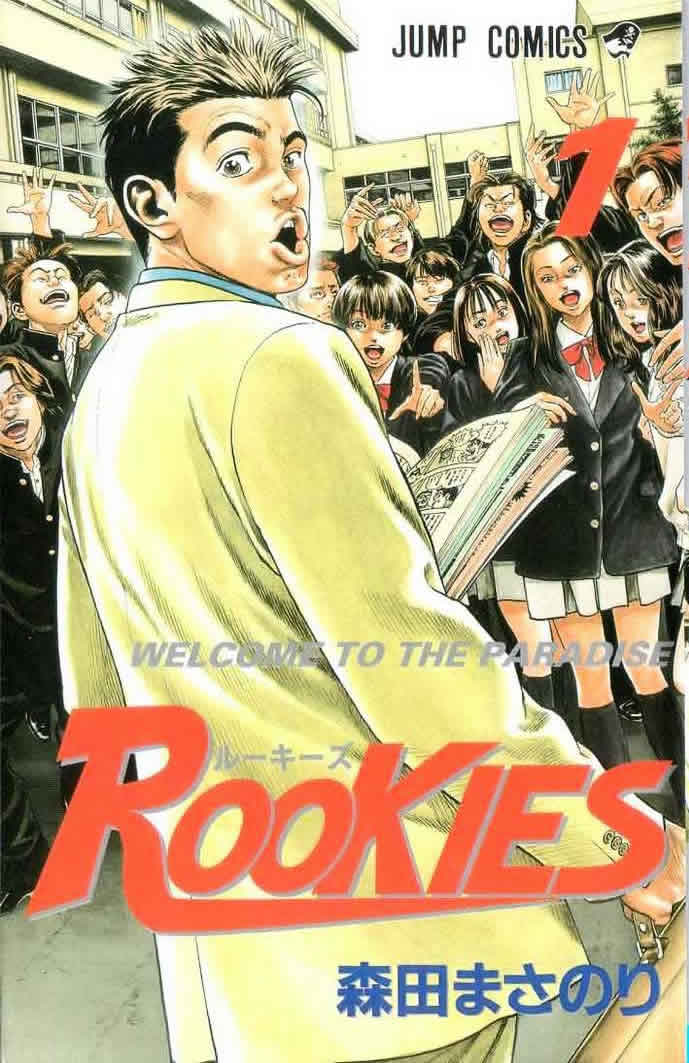

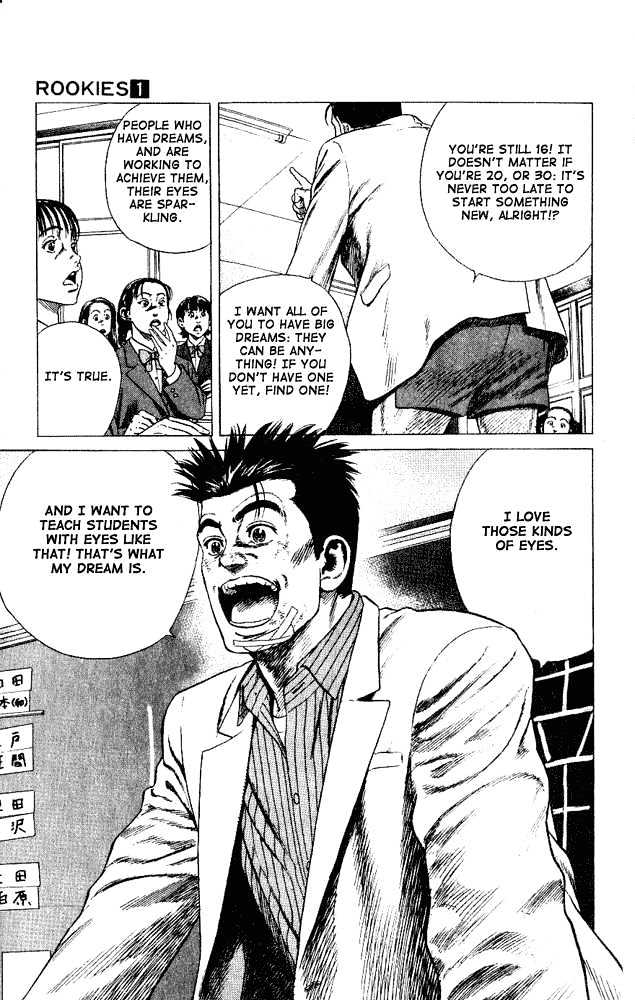

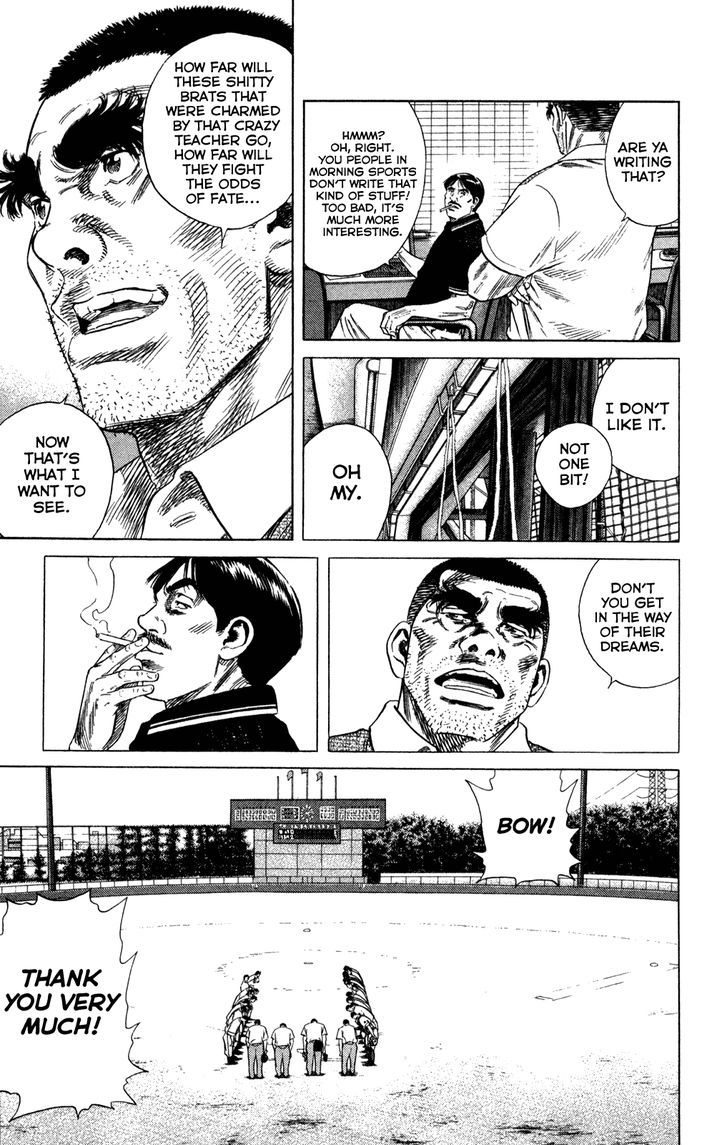

This tension is most evident in the stories that focus more on the delinquent students than their teachers, like Morita Masanori’s Rookies, in which an earnest, compassionate, and optimistic teacher, Kawato Koichi, takes a job at delinquent school Futakotamagawa and ends up being the baseball coach. Unfortunately, the baseball team, Nikogaku, is filled mostly with delinquents, and the team has been suspended from official competitions after turning a match into a fight.

These delinquents–the most powerful (or popular) group in school–are only in the baseball team because of the club room, which they use for gambling, having sex, and just general up-to-no-good-ness.

Rookies was published from 1998 to 2003, and fellow Gen-Xers will recognize themselves and people they know in the various delinquents, who are jaded and/or apathetic. Unlike Crows, which was a look back at Takahashi Hiroshi’s youth in the 1980s, Rookies is a portrait of the early to mid-1990s, much like Battle Royale. The characters are clearly members of a generation that were deeply affected by the 1991 Japanese economic crisis (and the general global recession). These teens have no faith in adults and have grown up expecting only disappointment.

So enter the noble teacher, Teacher Kawato, whose optimism and faith in others’ goodness is a direct contrast to the teens’ cynicism. It’s not a coincidence that Teacher Kawato always talks about the importance of having a dream and respecting people’s dreams, as well. Rookies is a direct response, a call to action by someone who clearly felt that a generation (or more) of Japanese teenagers needed encouragement and support. I’m a little surprised that it came from mangaka Morita because his Shiba Inu series is one of the most depressing things I’ve read, full of tragic stories of people who never managed to make it, but I suppose it makes sense because he’s interested in how people deal with their dreams and goals.

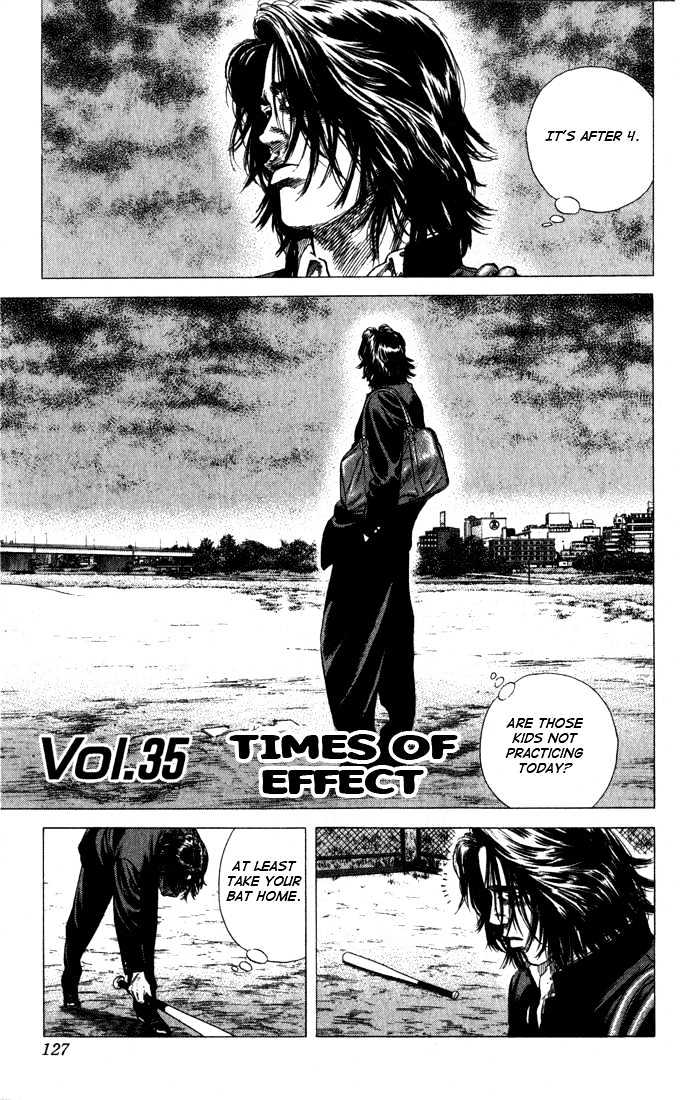

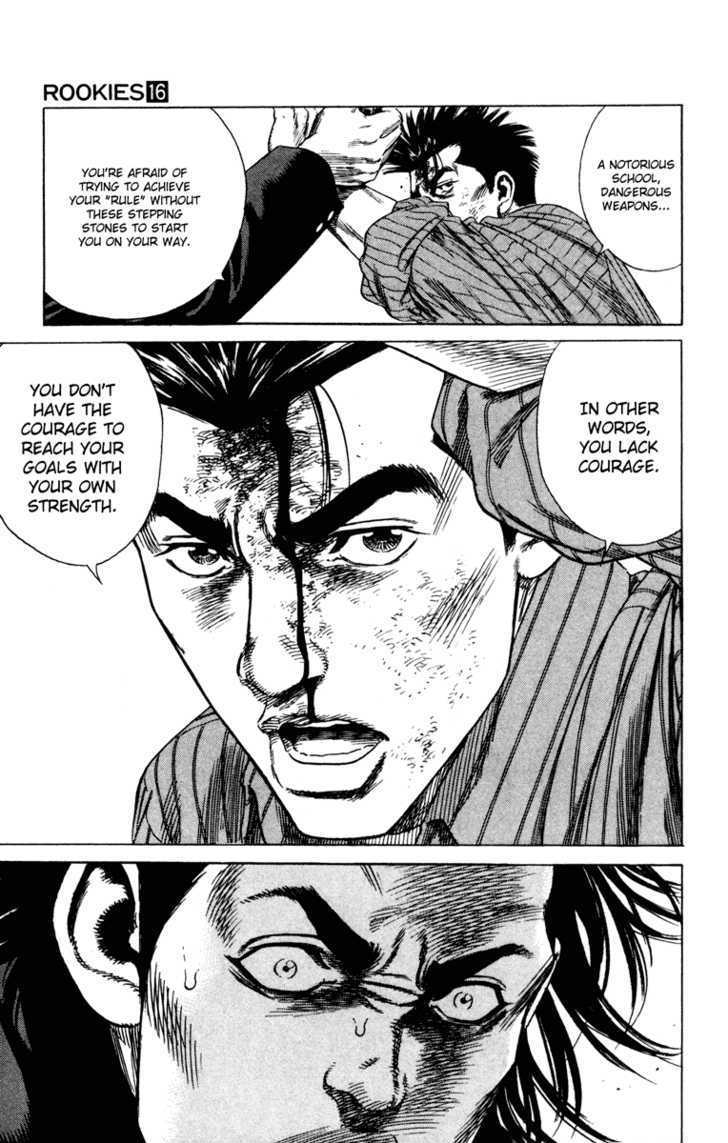

From the start, the delinquents expect that Teacher Kawato is too good to be true and are just waiting for him to disappoint them, and we get to see how each character handles Teacher Kawato’s attempt to reform them. The delinquents are led by Aniya Keiichi, who is basically a Chan Ho-nam type: same hairstyle, cool, handsome, beloved by girls, and admired by boys. Keiichi is also really cynical, having been a fantastic and talented baseball player in middle school only to realize that his talent may not be enough to get him to the national secondary school tournament in Koshien. Not wanting to face the prospect of failure, Keiichi decides to just give up and focus on stuff that doesn’t really matter.

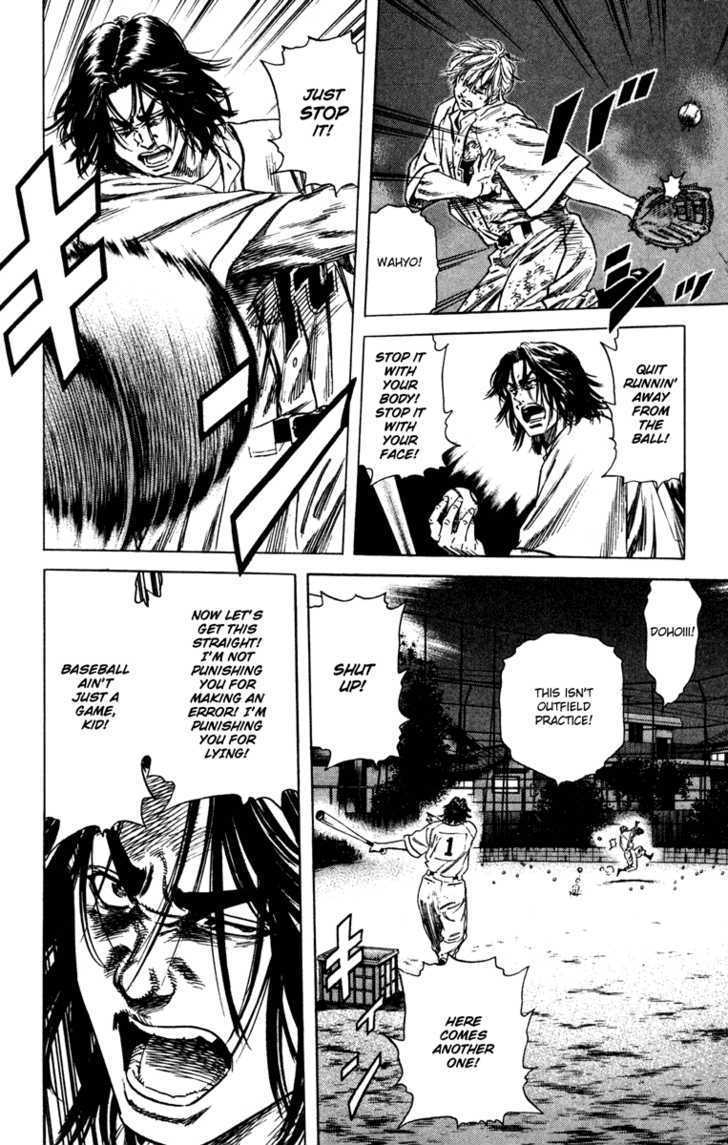

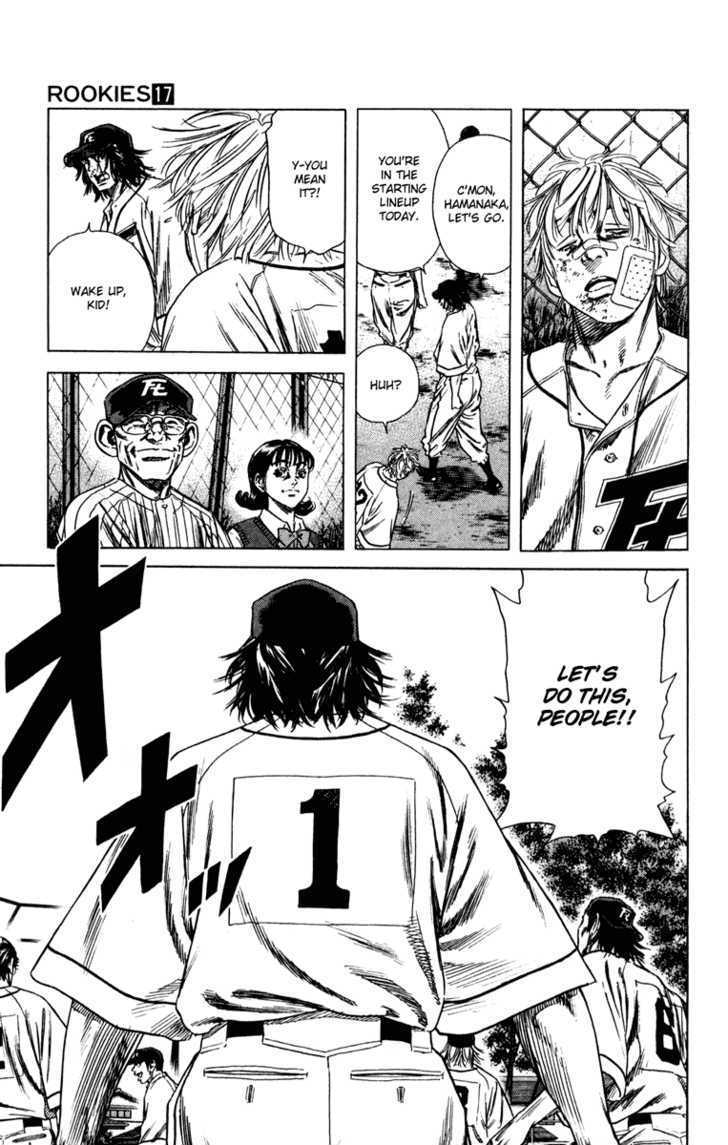

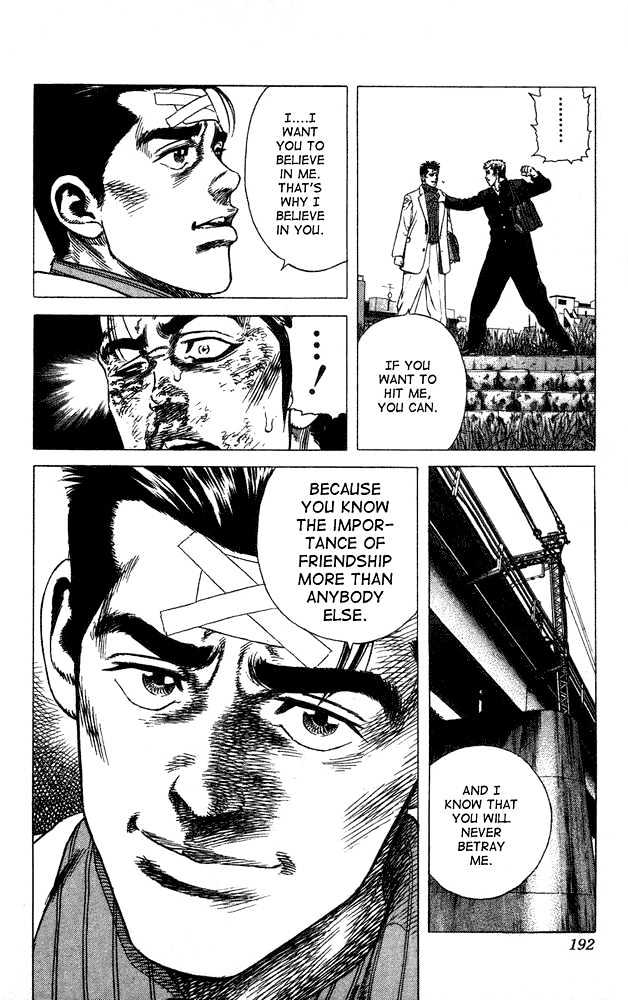

Hoo boy, do I know that feeling. Keiichi is given the star treatment in the series, since he’s not only hot but incredibly talented at baseball. Initially, Keiichi is dismissive of people that he believes aren’t talented enough (including himself), but thanks to Teacher Kawato’s influence, he realizes that raw talent isn’t as important as having a dream and pushing yourself towards it. Even though he’s quite gruff to his teammates, he learns to care about them and care about their dreams, as well. He goes so far as to help train a new recruit himself, and he gives the kid a chance, even though the kid is terrible at baseball.

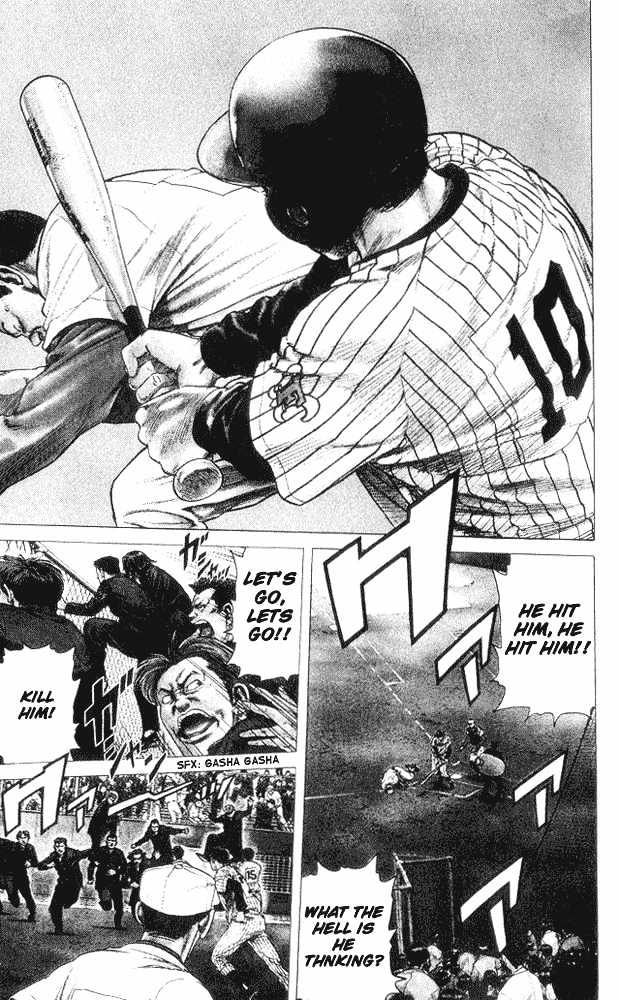

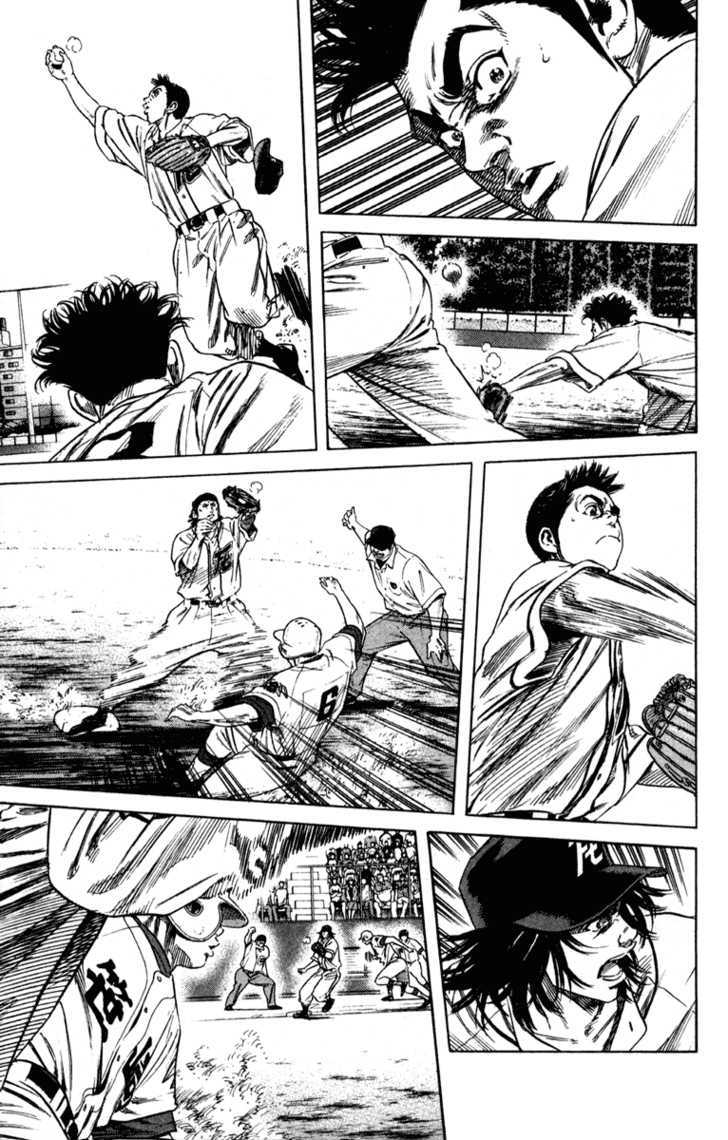

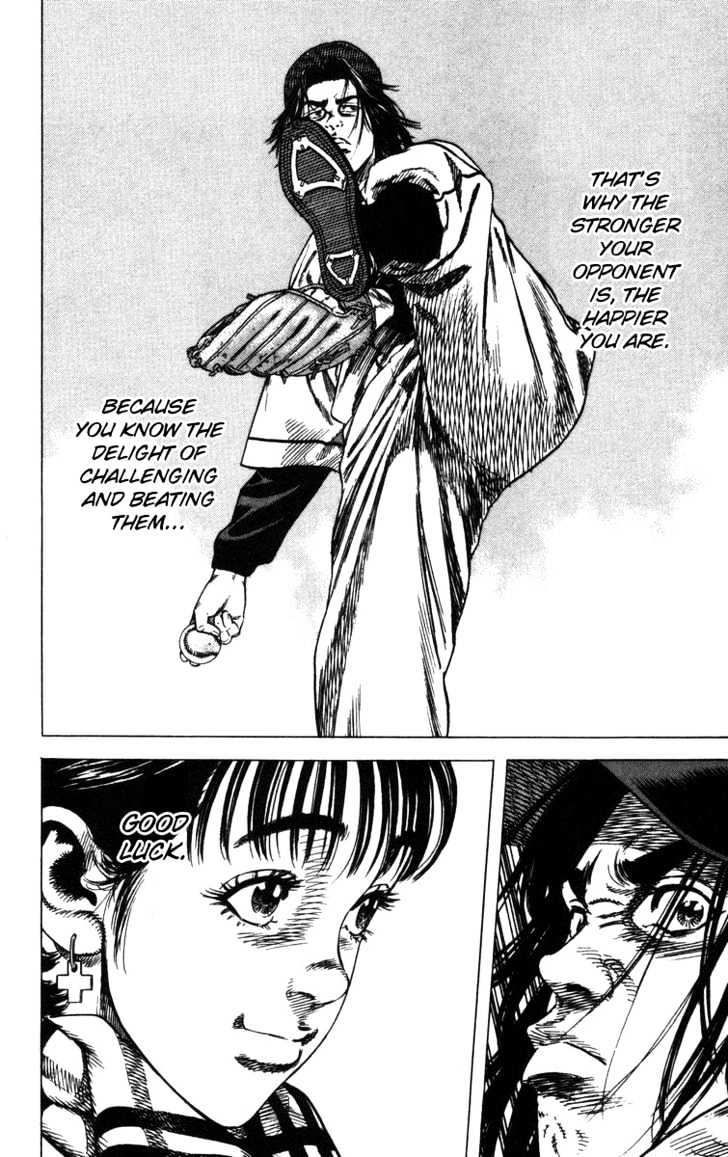

Incidentally, I want to pause here for a second to say that if you’re not sure about reading a sports manga, I think that Rookies is a lot like Slam Dunk in that you don’t need to know a lot about the sport to enjoy it. Mangaka Morita is fantastic at telling stories and the artwork is superb and well-integrated into the text. Just look at this page, where mangaka Morita has deliberately excluded sound and text to represent the kind of focus and concentration that makes everything around you disappear. Just look at the intensity of the expressions, the way the lines bring out an explosive energy.

That kind of attention to detail does a lot in bringing out the personalities of the characters. Even though we don’t really see the backstories of the characters, we get a good idea of who they are. For example, poor, bullied Mikoshiba Toru, the one member of the baseball team who isn’t a jerk and who really wants to play baseball, learns that Teacher Kawato has memorized all the names and faces of his students as a sign of respect for them. Toru starts weeping and from that tiny scene–the clearly drawn expression of regret and surprise, we realize just how worthless he’s felt all along and how much it means to him that someone thinks his feelings are important.

The manga makes it a point to contrast Teacher Kawato’s treatment of his students as individuals who each have their own unique talents and contributions with how adults tend to stereotype them as lazy or delinquent. It’s an indictment particularly of the education system, which treats students as nameless bodies who don’t deserve respect and need to be crushed into obedience.

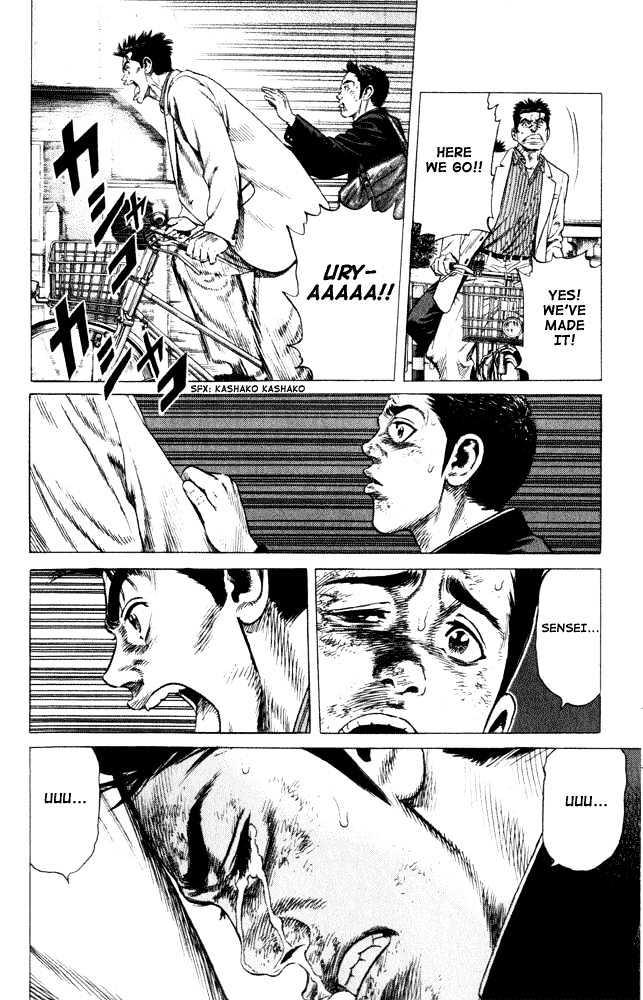

Teacher Kawato not only extends his respect and help to bullying victims but also to the scarier delinquents, in whom he recognizes the same yearning to dream, to be respected, to have friends. Shinjo Kei, the scariest delinquent in the group, ends up attacking and hurting his own friends when they begin to take playing baseball seriously. But he’s not doing it to be an asshole (well, not entirely), it’s because he’s terrified of losing his friends and of changing a situation where he feels comfortable, so he lashes out the only way he knows, which is with violence.

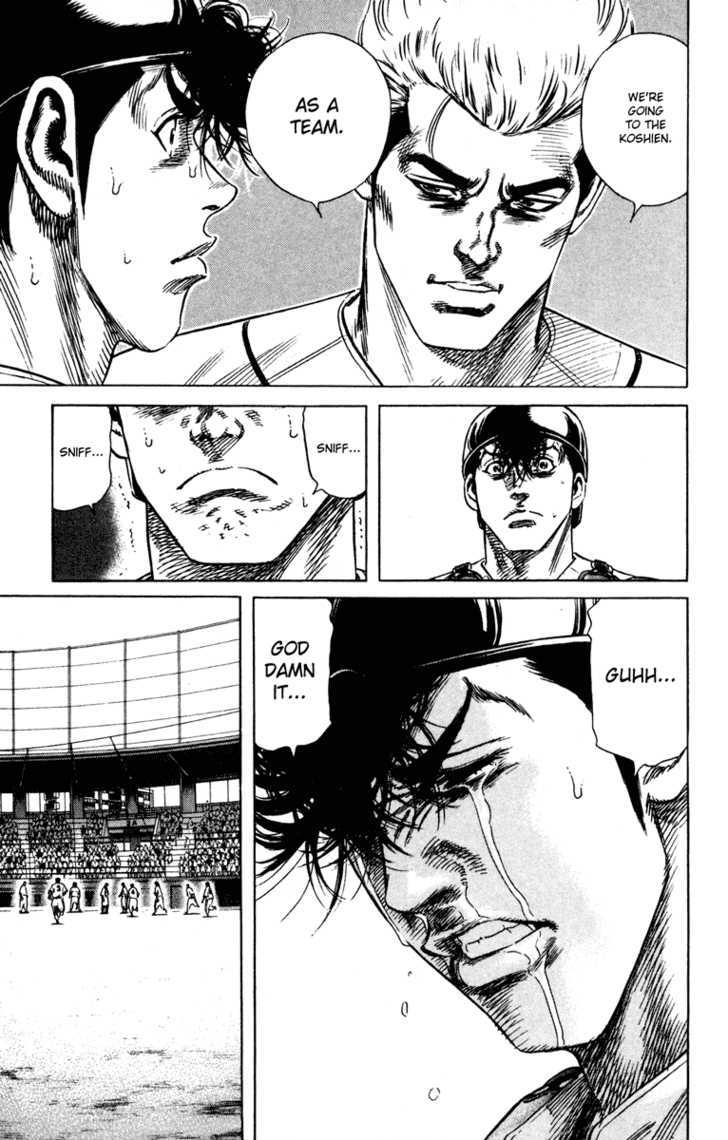

We also see the flipside of this loyalty and love for his friends when Kei steps in to join the team later when they need him the most. Again, it’s Teacher Kawato who sees that love in Kei and encourages him not to run away from it and to show his true self. And Kei doesn’t disappoint: out of everyone, he is the one who understands the most what it means to be a team. In one of the major challenges to the Nikogoku team on their way to the Koshien finals, Wakana Tomochika’s finger is broken by a baseball, but he hides his injury and continues to play because he doesn’t want to let the team down, and he’s also afraid of being left behind as they go on their Koshien journey.

Of course, because of his injury, Tomochika’s playing gets worse, but it’s only Kei, the person who values friendships the most, who understands Tomochika’s reluctance to speak up about his injury. He tells Tomochika that a Koshien victory will still include him. That two-tone hair also reminds me of my family’s old Nissan Sentra that had two colours after being sent in for post-accident repairs because the second colour was on sale, and they didn’t care if it matched the original colour.

This is where regular delinquent stories and teacher-redeeming-delinquent stories tend to diverge: the former assume that delinquents are being their truest, happiest selves as delinquents, while the latter assume that delinquents are lashing out because they’re afraid or unhappy and being a delinquent isn’t really who they are. They have real dreams that they simply don’t know how to express properly because no one has given them the right guidance, and they’re afraid that these dreams are out of their grasp, making them either apathetic like Keiichi or violent like Kamisaka below.

In Rookies, thanks to Teacher Kawato’s guidance, the delinquents learn to embrace challenges and fear, and that is what gives them their strength and ability to win.

Through the delinquents’ stories, Rookies is suggesting that the biggest cynics are usually the most sensitive and idealistic people who become embittered because the world doesn’t live up to what they imagine it could be. Delinquents are orchid children, who “are highly sensitive to their environment, especially to the quality of parenting they receive. If neglected, orchid children promptly wither–but if they are nurtured, they not only survive but flourish. In the authors’ poetic language, an orchid child becomes ‘a flower of unusual delicacy and beauty.’”

I doubt mangaka Morita knew about the orchid children study before writing Rookies, but it’s a testament to his powers of observation that he was able to instinctively see it. In Rookies, orchid children need to be nurtured by dandelions like Teacher Kawato, who “seem to have the capacity to survive–even thrive–in whatever circumstances they encounter. They are psychologically resilient.” He makes these students believe in themselves and their teammates enough to dream about reaching the Koshien, and along the way, he not just redeems the delinquents, but everyone else around them, including adults like the principal and vice-principal who hadn’t believed in the delinquents.

In fact, when it comes down to it, it often seems like stories where teachers redeem delinquents isn’t really about redeeming the delinquents so much as it’s about redeeming other people, especially adults. The delinquents are only reacting to the stress that’s placed on them, and their struggle to help themselves is something that can also heal other people. It’s also a reminder–or a wish-fulfillment fantasy–that not all adults are greedy, power-hungry, or ruthless, and there are those who genuinely care about helping those who are struggling.

This is not to say that Rookies is about the delinquents achieving success like suddenly becoming model students and upright citizens and getting great jobs at a bank or some other prison. Rookies is about the process of trying and failing and learning as you go after your dream, but most importantly, it’s about caring about yourself enough to have a dream in the first place.