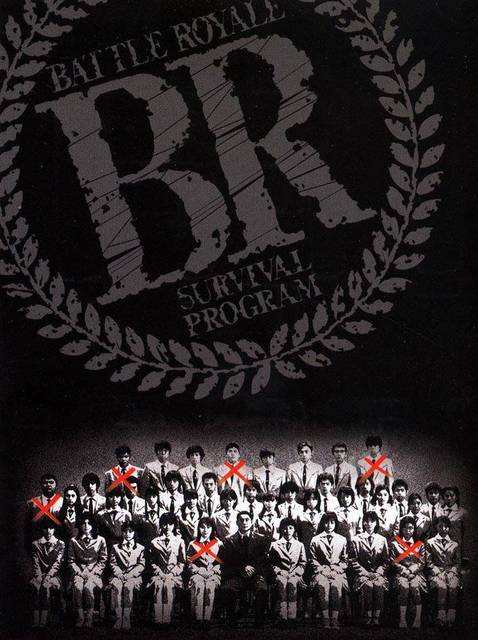

Note: Part 5 of our Tough Guys, Gangsters, and Delinquents in Asian Pop Culture series. If you haven’t yet, check out the other entries in this series to get a complete picture of what the 1990s was like as we move on to the 2000s with controversial child murder movie Battle Royale! Again, everything is spoiled to death here so if you haven’t seen Battle Royale and wish to remain untouched, please be warned!

Let’s get the basic stuff out of the way first: out of all the films, manga, and TV shows I’ll be covering for this series, none of them has ever reached the peaks of controversy that Battle Royale has.

It’s a film that has been never been officially screened in many countries, either because of an outright ban or because no distributor dared pick it up. And despite all of that, Battle Royale has a hugely influential pop culture presence.

The controversy around Battle Royale is often focused on the violence of the film, not necessarily because it’s unusually bloody (at least, anyone who reads shounen manga won’t think so) but because it involves children and is done with the approval of the adults in the movie. The movie’s plot centres around the Japanese government’s effort to control delinquency by forcing randomly chosen classes to compete in the Battle Royale game on a remote island, where the kids have to kill each other and only the last one standing gets to leave.

Of course there’s always a lot of handwringing whenever adults think that kids are becoming delinquents and doing sociopathic shit, but the film added fuel to the fire by basically accusing adults of being complicit with this behaviour. The actions of the adults in Battle Royale are just an extreme form of how they already force kids to compete with each other in order to succeed in real life.

Director Fukasaku Kinji (who did a lot of yakuza films as a younger director) also tapped into the fear adults had that the ruthless and exploitative system they’d supported for so long was failing them, and because of that, their own kids would turn against them. Fukasaku suggested that a lot of the anxieties and misbehaviour that kids had during that time came from their disappointment in adults, who’d emerged from the 1990s recession with a lot less confidence and authority. And without this authority, they couldn’t command any respect, leaving them to resort to terrifying and intimidating kids, who could see through their bullshit.

Battle Royale emphasizes that no matter how wild delinquents can get, at the end of the day, they’re still at the mercy of adults and mainstream society. Teacher Kitano (Takeshi “Beat” Kitano) can’t get any respect from his students or even his own daughter, but he gets his revenge when his class is sent off to the island where they’re expected to kill each other–not to mention that he actually kills a couple of the students, too.

The past films and manga that I’ve looked at for this series are usually set in the worlds in which the gangsters and delinquents operate. We see them in their element and see how they thrive or fail within the rules of their own world. Battle Royale is unique in that it takes delinquents and puts them in a situation where they have very little control over anything. And they’re barred from forming the friendship bonds that characterize delinquent life, making them completely powerless.

While in most delinquent stories, adults don’t really show up unless there’s an occasional need for a mean authority figure or a kind mentor, the presence of adults looms over the entire film. While the power that adults have over the survival of kids in real life is taken to the extreme here, Fukasaku makes sure to portray the adults as failures themselves: the main protagonist, gentle Nanahara Shuya (Fujiwara Tatsuya, who looks exactly the same in 2017, good Lord) is abandoned first by his mother and then later by his unemployed father through suicide. Souma Mitsuko’s (Shibasaki Ko) mother pimps her off to a pedophile. And there’s Teacher Kitano, of course.

Although the kids aren’t exactly angels–with the exception of Shuya and Nakagawa Noriko (Maeda Aki)–the movie is very sympathetic to them. We see some kids letting their worst impulses run free, like Mitsuko, but we also see why they’re lashing out. Also, most importantly, despite the fact that the system is rigged to prevent bonds from forming, quite a few kids form alliances to protect each other and figure out a way to survive.

In Asian pop culture, the world of delinquents and gangsters is often contrasted against the mainstream world as a place where government and laws don’t need to exist because its inhabitants are bound to a code of honour and friendship or brotherhood. What’s funny about this is that it basically says that the violent world of delinquents has more decent people in it than mainstream society, which needs the threat of laws and penal systems to make people behave decently to each other. And to go further, there’s also the implication that in mainstream society, greed and selfishness are more important than friendship and honour.

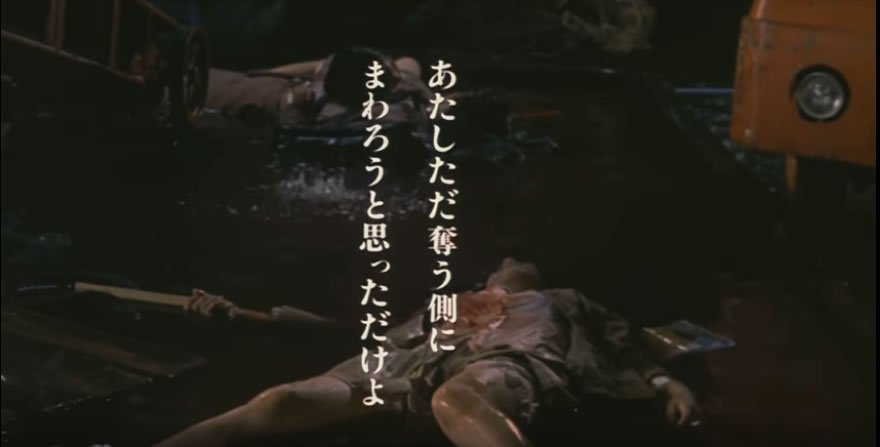

As I mentioned earlier, the Battle Royale game itself is a metaphor for modern capitalist society, where you need to be selfish and manipulate and/or reject friendships in order to survive. Mitsuko is a perfect example of this kind of attitude, which is why she ends up having such a high body count. The film does not glorify this sociopathic behaviour, though, and it explicitly shows us that Mitsuko is like this because adults have failed her. We also find out as Mitsuko dies that she was lonely and unhappy the entire time.

It’s delinquents, the kids who defy the game’s (and society’s) expectations, who triumph in the end because they adhere to the code of honour and friendship. Of course, it’s not easy because you have to trust the people around you, and without that bond, things can degenerate into paranoia and suspicion, like with the girls that have banded together in a lighthouse who end up killing each other.

That scene really struck me because usually, delinquent stories tend to be homosocial and focused only on boys and men. In Battle Royale, girls are as big a part of the story as their male peers; they kill and strategize and rescue as much as the boys do. I did think it was interesting that it’s the girls who end up being jealous and suspicious of each other and destroying their own group, while the boys are often killed by people who are outsiders to their group instead of being betrayed by one of their own. It makes me think of how much I often use “brotherhood” to explain deep, self-sacrificing friendship because I’ve been conditioned to think of “sisterhood” as something different.

It’s also the boys who are more proactive about figuring out a way to get off the island while the girls who band together just want to survive somehow. I don’t think the film is necessarily saying that girls are less capable or forward-thinking than boys, and maybe I’m reading too much into this, but it looks a lot like a commentary on how the safety concerns that girls have (sexual and physical assault) can often be physical or mental obstacles when it comes to doing shit other than protecting themselves.

It makes me think of Hobbes’ Leviathan, where he’s like women and men have equal amounts of prudence and skill, but he recognizes that men do have an individual advantage over women in terms of physical strength. Women aren’t inferior or less equal, it’s just that they have to worry about some extra shit, although they have other advantages, too.

And like Leviathan proposes, it’s the conventions and contracts that people make to ensure their survival that saves the lives of both Shuya and Noriko since they are helped by Kawada Shogo (Yamamoto Taro, now an anti-nuke activist who is kind of awesome). Shogo is a former Battle Royale winner who had to kill his best friend in order to save Keiko, the girl he loved, only to kill her in the end, as well. He returns to the game to try to get revenge on the organizers and also to try to figure out what Keiko meant with her last words: “Thank you.” Shogo dies as the kids escape thinking “At the end, I’m glad I found a true friend,” which is pretty much a delinquent slogan.

Teacher Kitano also dies in the end after unveiling a disturbing painting he’s done of Noriko surviving Battle Royale while the corpses of her classmates lie around her. I should mention here that for a delinquent, Noriko is quite sweet and the least rebellious of the lot, and she doesn’t really have much to do except be the innocent victim and damsel in distress. She’s supposed to represent the lost innocence that Teacher Kitano (and other adults) wish children still had, and I do think it’s important that she survives because of the delinquents who protect her despite the horrors and dangers that adults put her in.

And speaking of horrors, Teacher Kitano get the Wizard of Oz revelation as being just another weak human whose lack of meaningful connections to others has made him into a vindictive, unhappy person.

One of the final images of the movie is a bunch of crows pecking at garbage, which is quite meaningful and most likely deliberate, especially considering the symbolism behind crows in delinquent stories.

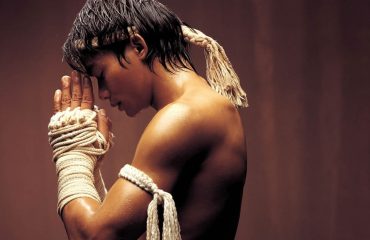

As I absolutely love Dragon Ash’s song that appears in the credits, I’m going to leave the video here for you to enjoy. As for the next installment of this series, we’re finally turning to Southeast Asia with Ong Bak!

(Update) I’ve been asked why I was so reluctant to write about Battle Royale in the first place, and the truth is, I thought that there were just too many articles about it in English already. But when I finally started reading through them, I realized that they were mostly written by Westerners who had no clue about the film’s context within Japanese pop culture and history. While some reviews were decent, there was a disturbing number that had this titillated focus on killer schoolgirls, which I think speaks to how exciting and sexually arousing the thought of dangerous Asian girls are to a certain group of creepy people. Also, I found an article that referred to a wannabe rapist as simply as a “would be deflowerer”. Uh…okay, dude.