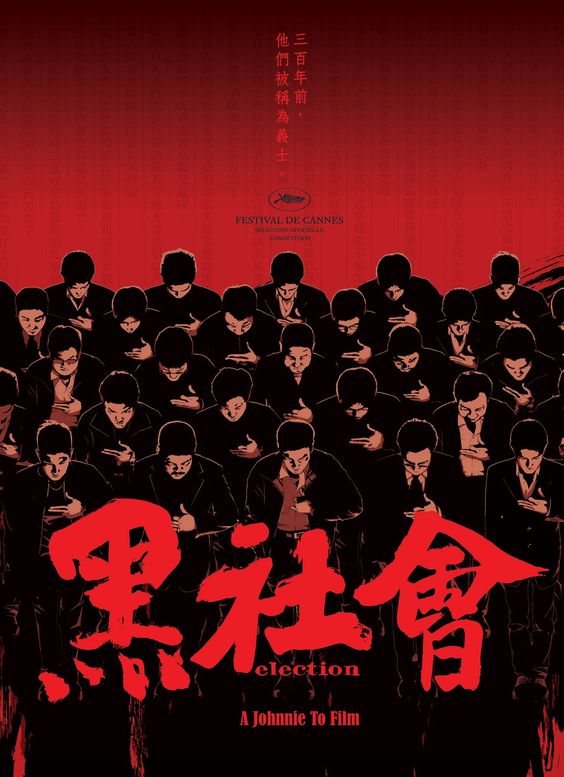

Note: Election is the latest entry in the series Tough Guys, Gangsters, and Delinquents in Asian Pop Culture, and it’s another film from the incredible Johnnie To, whose work will probably be making a lot of appearances in this series. Again, spoilers!

Before we start, I’d like to spend a couple of minutes admiring the poster for Johnnie To’s Election. Did you know that the hand signs that the actors are making in the poster are legit? Here’s a handy guide from the Election Cannes press book below, I’m sure I don’t have to remind anyone to not be stupid and start flashing these around in Hong Kong or Chinatown. At the very least, you’ll catch a cop on your ass.

Also, thanks to the anti-triad colonial laws in Hong Kong, any movie that shows these signs are immediately given a Category III rating (which is similar to the US Rated R). The more you know!

from cinemastrikesback.com

Violence is obviously one of the most important themes of gangster stories, and it can be traced to the fact that underground societies like the triad and yakuza are all honour cultures, where your social status and authority–if you’re a man–is tied to your willingness and ability to defend yourself, your loved ones, and your property. If you allow people to disrespect you and get away with it, you become nothing, and you can’t even rely on the law to help you.

We see how the low-level triad members like Thirteenth Sister’s father in Portland Street Blues suffer because they have no status within the triad, and we also see in various gangster stories how people rise within the ranks because of how many people they’ve killed.

But while most gangster movies (including many of To’s own films) glamourize violence by having protagonists fight and kill in the coolest ways possible, making death and injury feel as casual as eating, To turns away from that to depict something more dismal and repulsive in the Election films, where a lot of horrific violence occurs without a single gun being fired.

To did a lot of research with actual triad members from different groups and made two films that were as close to reality as possible, to the point that triad members were irritated because they had been expecting something that would make them look cool, like Young and Dangerous, instead of Election, which revealed just how much triad societies, which ostensibly rely on brotherhood, tradition, and honour, have been corrupted by greed and money.

To said in an interview regarding the violence in Election, “What was important was not being graphic, but to emphasize the fear and anxiety in the gangsters’ world. That’s how gangsters operate, they impose fear. They use the word honor, but it’s really all about money and profit.”

To is referring to two things here, the first being that, without rule of law, honour culture means that you’re forced to fight and kill all the time to protect your status, and it’s easy to get stuck in a revenge cycle. The really interesting observation that he makes, however, is how defending your honour is also a very convenient pretext for covering up crimes done out of greed and a lust for power.

Triad societies have changed a lot from their origins as secret societies dedicated to the overthrow of foreign rulers (gee, I wonder why the British colonial government was so afraid of them?) to a modern criminal business enterprise. Actually I should note down here that the British colonial government even published a book about triad societies in 1960 but do take it with a grain of salt. The author himself admits that he’s not sure how much of his information is accurate because of the secrecy around triad membership.

Anyone who’s watched To’s films knows that he’s really fascinated by the idea of brotherhood, and in the Election films, he gets to dive behind the myth of brotherhood in the triad. Election 1 begins with a bunch of people reciting the thirty-six oaths, which is part of the initiation ritual that each new triad recruit must undergo. Incidentally, you may notice the number thirty six coming up a lot in Chinese culture (Thirty-Six Strategems, 36 Chambers of Shaolin, and so on). According to this article, thirty six has long been in historical use to mean “a lot” because it’s the square of six. Yeah, I don’t get it either, but it sounds pretty cool.

The oaths are pretty much all about how you’ll get punished for different betrayals, which foreshadows the actual betrayals that end up happening and go unpunished. It’s a pretty bleak and unromanticized view of how triad societies function nowadays.

The gist of Election 1 is that Wo Shing Society (a real triad society, by the way) is due for their Chairman election, which happens every two years. The two main candidates are Big D (Tony Leung Ka Fai), who is an unpredictable, flashy dude relying on bribes to get the chairmanship, and Lok (Simon Yam), who most of the old triad uncles agree is steady, calm, and respectful of traditions. I don’t even have to tell you which one is which in the pictures below.

Even though Big D pays out a lot of money, the uncles end up voting for Lok–but it’s clear that only one or two are doing it for the sake of upholding tradition and the society’s values. Most of the others are doing it out of self-interest because Lok has promised to expand their business, others out of spite because they despise Big D, and some just because they want to avoid trouble.

Naturally, this doesn’t sit well with Big D, who, in retribution, kidnaps and tortures Uncle Long Gun and Sam, whom he blames for his loss. These are the two elders of Jimmy (Louis Koo, who looks beautiful as ever but whose attempt to speak Putonghua in these films may be the biggest work of violence), who asks Lok for help in rescuing them.

The kidnapping and torture sets into motion a rift within Wo Shing as it’s a direct attack on the traditions and values that keep the society from falling apart. Big D makes it worse by threatening to create his own society and start a war. This causes the previous chairman to hide the Dragon Head Baton that each chairman safeguards, as the Baton represents all the power and authority of tradition, and no leader can rule Wo Shing comfortably and legitimately without it.

Even though it’s obvious by now that brotherhood is easily betrayed and that there’s very little honour, the Baton–much like the thirty-six oaths–allows everyone to pretend otherwise. After all, the more corrupt an organization is, the more it needs to rely on hypocrisy and symbols of legitimacy to hold together.

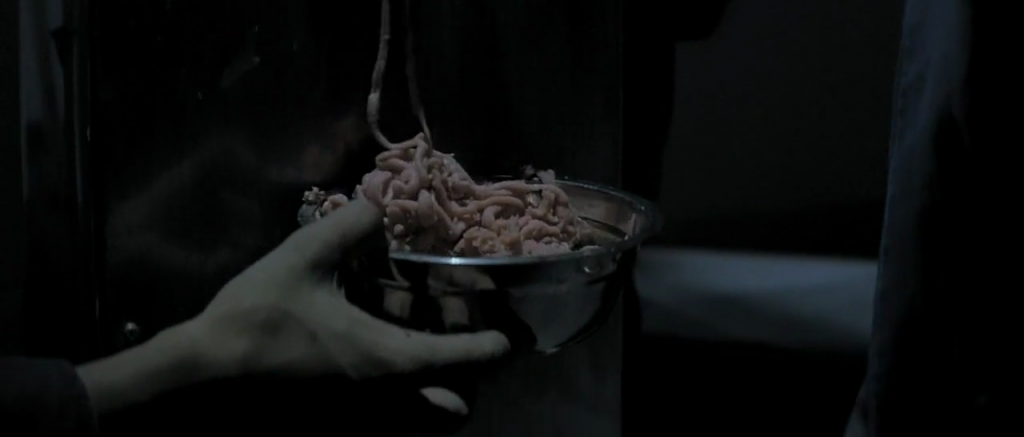

Of course, there are still brothers who have honour and loyalty–one being Jet (the wonderful and intense Nick Cheung), who ends up being manipulated and used because he’s too loyal and doesn’t question his superiors. I mean, this guy grinds up and eats a Goddamn spoon just because Big D told him to. Forget your favourite action scenes, this may be the single most badass thing ever put on film.

And the other being Big Head (my dream husband Lam Suet), who knows all the oaths and even recites them as he protects the Baton from being stolen despite being beaten with a log. These are the dudes who actually represent loyalty and honour, except in the modern triad society, they’re only useful as martyrs and loyal errand boys. They will never get actual power because that’s not how it works anymore.

Lok, on the other hand, who originally presents himself as the protector of the society’s values and beliefs, turns out to be just as venal and power-hungry as Big D. In fact, he may be worse than Big D because he hides his ambition under a veil of upholding tradition. As Election 1 progresses, we see Lok get rid of everyone in his way: murdering the ex-chairman’s son and forcing the old man to commit suicide, as well as killing Big D and Big D’s wife in front of his (Lok’s) own son, who is understandably traumatized.

And throughout it all, he still maintains the façade of tradition in order to ensure that his legitimacy isn’t questioned. I thought that the film showing Lok hiding the Baton in the columbarium niche where his wife’s ashes are kept is the perfect metaphor for how he hides his ambition from everyone.

In Election 2, Lok continues to keep up this façade by pretending that he’s going to support other sworn brothers in their quest to become the next chairman while secretly plotting to continue for a second term, which is against the rules. Unfortunately for him, Jimmy, who has been trying to move out of criminal enterprises and into more legitimate businesses, especially in mainland China, is being strong-armed by the Chinese government to take over Wo Shing.

Jimmy initially resists becoming chairman, explaining that all he wants to do is make money and that he has no interest in leading Wo Shing. I really can’t blame him because one of the things I joke about with my Chinese friends is how sorry I am for Xi Jinping because it is SO DAMN DIFFICULT to actually govern a bunch of Chinese people. Have you ever tried to reason with an elderly Chinese auntie or uncle? I can barely get my mom to throw out moldy leftovers and one of my aunties hasn’t taken down her Chinese New Year decorations for FORTY YEARS despite being gifted a box of new decorations almost every year. Her decorations are older than her children and look like Monet watercolours at this point. Now imagine an entire country full of stubborn-ass Chinese people like that or, in Jimmy’s case, over 50,000 Wo Shing Society members. (But seriously, though, Chinese people are some of the worst people to govern because we’ve been fucking with emperors and kings for over 5,000 years, and we don’t respect authority).

In Election 2, the Chinese government is willing to tolerate the presence of triad societies out of pragmatism: they know it’s impossible to root out crime completely, so they’re willing to work with the triad on the condition that they don’t cause any trouble and keep things peaceful.

If you wonder why China’s leaders would think that way, it’s because China has one of the most violent and chaotic histories of any civilization, with almost every change of dynasty (and sometimes even just emperor/empress) involving a lot of death and destruction. In the past hundred years of Chinese history alone, there’s been war, foreign occupations and looting, massacres and mass rapes, famine, revolutions, revolts, corruption, terrible poverty, and lots of suffering. At this point, Chinese leaders just want stability, and they’re willing to sacrifice a lot to make sure that China isn’t plunged into the same craziness again.

Many of the methods they’re using are familiar to any Southeast Asian Chinese. It’s been commonly observed in overseas Chinese communities in Southeast Asia that they tend not to become involved in local politics overtly. Instead, they concentrate on building wealth so that they can influence government policies. Again, this is partly due to the lessons of Chinese history: emperors and governments come and go, but money influences everyone. But another equally important reason is that using money as both a carrot and a stick is possibly the most effective way to make people do your bidding.

Jimmy knows the value of money, which is why he doesn’t understand why Lok and so many other triad guys want to be chairman. He even asks Lok what he (Lok) gets out of being the leader of Wo Shing. But despite his resistance, Jimmy finds himself in the same money pinch that he’s put other people in, with the extra sad irony that the only way he can do legitimate business is by immersing himself even deeper in the triad.

It’s no surprise that the mainland authorities would rather have someone like Jimmy, who understands the importance of money and stability, in charge. He is the new breed of triad gangster; he’s not invested in honour culture, nor does he pretend that he does, like Lok. He doesn’t even care about symbolic trappings like the Baton. But once Jimmy decides on this path, he’s revealed to be the most frightening gangster of all.

As part of his plan to get rid of Lok, he captures Lok’s bodyguards in order to force them to agree to murder Lok on his behalf. The bodyguards resist despite being tortured with dogs and bludgeoning until Jimmy hacks off the limbs of one of the bodyguards while the poor guy is still alive and puts them into a meat grinder, feeding the ground human meat to the starving dogs. To fortunately spares us the screams and gory details of the scenes, but we see enough to know how terrible and awful everything is. Even the tough hired killer Jimmy ropes into helping him is sickened by the entire thing.

Jimmy terrorizes the rest of the bodyguards so much that they agree to murder Lok, their fear overriding loyalty. Jimmy insists on paying them because the blood money makes it a deal that they cannot renege on. They go on to have a meal together where everyone looks somewhat stunned with low-grade terror while Jimmy has the dead-eyed look of someone who has spent way too much time working overtime and chasing deadlines while subsisting on cheap ramen and just does not have any fucking patience left.

Jimmy has got to be one of the most complex and depressing characters in the Election films. He’s a reasonable guy who just wants to do normal things and live a normal life, but ends up committing the worst atrocities exactly because of these things. In order to be a legitimate, normal businessman, he goes further than a typical gangster like Lok, who glorifies in violence and power. Jimmy just wants to be left alone, and that’s why he’s so dangerous and frightening.

Director To is pretty well-known for his superb casting choices, with each role inhabited so naturally by the actors that it’s hard to believe that they’re not actually these characters, but I want to make a special note about Louis Koo’s casting as Jimmy. With his dimples and pretty features, Koo looks almost harmless and boyish next to all of these grizzled uncles, so it’s extra terrible when he finally gets down to business.

In the end, Jimmy pays the price when he realizes that the Chinese government wants him to turn Wo Shing into a family enterprise, meaning that he can never get out of the triad, and not only that, his son is doomed to be part of the society as well. The only way out is to give up everything, including his businesses, and he’s sacrificed too much to do that.

I want to reiterate that when I first started writing this series, I never expected to see so much anti-capitalist subtext in these delinquent and gangster stories. And out of all the stories I’ve reviewed so far, the Election films stand as the greatest condemnation of capitalist greed. You may get all the money that you want, but you’ll find the price is more than its value.

Election 2 ends with a quietly despairing scene as Jimmy stares out of a barred window; there’s no escape from his decisions now. He’s burdened with power he didn’t even want in the first place, and he’s equally burdened with the knowledge that he has to keep committing more heinous acts to keep it in his hands. And worst of all, one day, his own children’s hands will be stained with blood, as well.