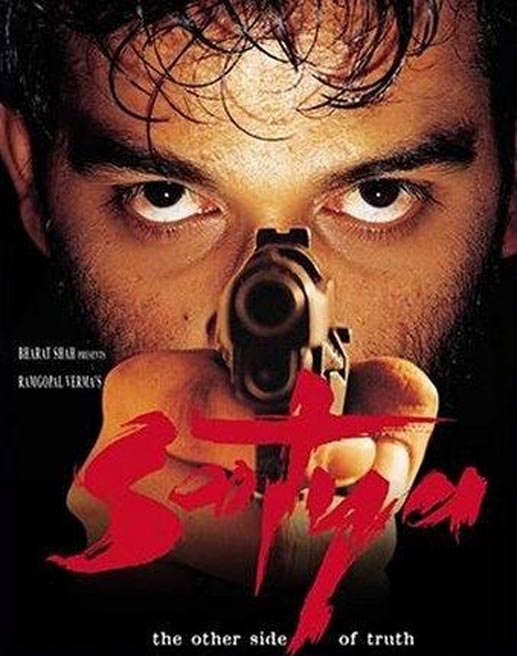

Note: This is the latest installment of Tough Guys, Gangsters, and Delinquents in Asian Pop Culture, and spoilers abound like dancers in a Bollywood film. India has produced a lot of fancy gangster and delinquent films, but Satya‘s grittiness and social commentary really caught my attention when I watched it. Anyone who’s lived in a corrupt Third World country will understand all the complexities that it brings up.

Manoj Bajpayee, who plays gang leader Bhikubha “Bhikhu” Mhatre, was the breakout star of Ram Gopal Varma’s Satya, the first in his Gangster trilogy, when it came out in 1998. The sudden stardom and acting awards probably made him feel better about losing the part of Satya (played by J. D. Chakravarthy), which had been initially promised to him.

I would be really surprised if Bajpayee hadn’t gotten huge after his tour de force performance: as Bhiku, he is completely mesmerizing and charismatic and yet it’s such a lived performance that it doesn’t feel like he’s acting at all. Bhiku is that moustache uncle with a thick gold chain, matching Rolex, and floral shirts that would make Migos rend theirs in envy.

He is that uncle who lets you sip his Napoleon XO, slips you a couple hundred dollars for talking back to the teacher, and laughs that really loud laugh even when your grandma is scolding him for getting into trouble again. He is also the uncle who, during one of his terrifying rages, punches a hole in the wall, smashes a chair into the mirror, and tosses your poor auntie around like she’s a leaf in a hurricane. Watching Bajpayee, I was half-convinced that we’re related somehow–that’s how completely he embodies Bhiku’s character.

Bhiku is a grown-up delinquent who ends up being a gangster because he only knows to do two things well: fight and be a loyal friend. But like the Election films showed a few years later, the crime world is full of greed and disloyalty, and people like Bhiku don’t live very long because there just isn’t room for violent, honourable men. And even people like cold-blooded and calculating Satya can only survive for as long as they can keep their humanity locked away.

At the end of Satya, Director Varma includes a title card explaining that he intended the film to show how much damage and suffering crime causes, and that he hoped the film would warn people away from that lifestyle. Although it’s possible that Director Varma meant exactly what he said, I can’t help thinking that this was also to cover his ass because Satya doesn’t come off as a morality film. I wouldn’t say it glamourizes crime, but if anything, it humanizes the people who are caught up in it because they simply have no choice. Director Varma wrote: “My tears for Satya are as much as they are for the people whom he killed.”

That empathy comes through clearly, but the film itself points a finger not at the petty gangsters like Bhiku and Satya but at the systems and institutions that push them into crime. In fact, the movie opens by juxtaposing the slums and impoverished residents of Mumbai with scenes of crime and violence, with the narrator telling us that it’s a city where the wealth gap has created two different worlds.

Like the other movies and films I’ve looked at for this series, Satya is a critique of greed and power but this time through the context of institutionalized and systemic poverty and corruption. Satya never means to be a gangster, but as soon as he arrives in Mumbai, he has to endure the indignities of poverty that drive him towards crime. He’s only able to afford a bed at a stable for cows, he works as a waiter at a restaurant where the patrons abuse him, and then he gets shaken down by some local thugs at the stable.

If you’ve grown up in a Third World country and have a modicum of empathy and observational skills, Satya will be instantly recognizable and familiar. Being poor in a society that despises poor people and is structured to keep them poor generation after generation, means most of the time, poor people just bow their heads and accept injustice.

But to have Satya do that would make this film into a documentary, so instead, unlike in what happens most of the time in real life, he fights back. Like Ting in Ong Bak, he attacks the people who try to take advantage of him, but unlike Ting, who is motivated by his goals and innocence, Satya simply does not want people to fuck with him anymore.

The moments where he refuses to let those who have more power or money strip him of his dignity are full of catharsis, vindication, and, of course shock value. This just doesn’t happen in the Third World, and it’s the moment that we realize that he is different from everyone else who’s been ground down by poverty.

As Satya, Chakravarthy’s eyes, normally the melancholy ones of a romantic hero, are drained of life and hope. Satya has the eyes of a man who knows that his life has no value, and, in classic gangster movie style, does not care. Despite knowing that Jagga (Jeeva) is a feared gangster, Satya retaliates when Jagga tries to humiliate him by wiping his foot all over his face. Dudes, I don’t blame him, that’s disgusting.

Satya lands in jail on false rape and pimping charges thanks to the corrupt police paid off by Jagga, and there meets Bhiku, who takes an interest in him because Satya won’t put up with being bullied (after Bhiku tries to bully him first, of course).

Bhiku, who is full of life and warmth, is fascinated by Satya, a man who isn’t afraid of anything because he’s been pushed so far to the margins of life. From the start, he has nothing, not even fear. He appears without a past, a family, or even a last name.

Although Satya is introduced like a classic man from nowhere, the kind of man who rides into town to address the sins of the people who live there, not having a past or ties to other people doesn’t just make him a strange and intimidating person, it also makes him someone to be pitied.

When Satya’s neighbour Vidya (Urmila Matondkar) discovers that he has no family, it moves her to tell him not to be ashamed, and it’s a moment where we see Satya actually feeling emotions. In fact, look at his eyes whenever he’s with Vidya, they’re suddenly full of life and feeling. In Satya, like in the old Westerns, women are the civilizing influence on hard killers, but it’s this softening and emotional vulnerability that becomes Satya’s downfall.

With Vidya, Satya finally manages to experience happiness and love; once he’s had a taste, it becomes more and more difficult to him to handle his criminal life. Poverty makes people do terrible things, but love and kindness can go a long way in redeeming them.

Or rather, a certain kind of love and kindness. In his own way, as a gang brother, Bhiku is equally loving and kind. He gives Satya money to buy a ring for Vidya, helps him find a way out of the gang life in Dubai, and, as a semi-joke, says that he’s jealous of Vidya’s closeness to Satya.

But male friendships and love in gangster films don’t have a domesticating influence, and in fact, it can lead to disaster. It’s Bhiku’s love for Satya and trust in him that leads him down a violent path. Satya encourages him to put a hit out on some of the most dangerous men in Mumbai, including the new police commissioner and the gangsters who’ve fucked with him, like Jagga.

Bhiku’s defence of Satya against gang boss Bhau Thakurdas Jhawle (Govind Namdeo), who knows that Satya is behind the decisions to kill the other criminals, is ultimately what causes his death. After Bhau wins the local elections, he murders Bhiku and orders Bhiku’s gang brother Uncle Kallu (Saurabh Shukla) and lawyer Attorney Mule (Makrand Deshpande) to get rid of Satya, as well.

I just want to stop for a moment here to pay my respects to Attorney Mule. Yes, he’s a traitorous bastard–he IS a lawyer, after all–but Goddammit, just look at that seriously cool motherfucker. If I had to go to court for a criminal case, this is exactly what I would like my lawyer to look like. Hell, this is what I hope I would look like.

With so many people after him–Bhau and his men, the police–Satya’s death is a foregone conclusion. He has one last chance to escape to Dubai with Uncle Kallu, who remains loyal to him, but he goes to see Vidya instead, thus damning both himself and Uncle Kallu when the police find and kill them.

If there’s any lesson to this film, it’s that to succeed as a gangster and a criminal, you have to divest yourself of humanity, loyalty, and love and give in to corruption and selfishness. In fact, you might gain even more power and succeed as a politician, like Bhau.

The critiques against power and money and how they’re tools of oppression aren’t subtle at all in Satya, and, speaking as a (privileged) Third Worlder, it’s amazing to see it so plainly expressed in a gangster film. And Director Varma doesn’t just present a one-sided argument excusing the poor for crime; he takes pains to show that these gangsters are causing suffering to others who are also poor and marginalized.

And even though the police are generally shown as corrupt and use the gang killings initiated by Bhiku and Satya as an excuse to commit atrocities (hm, sounds familiar), we also see things from the police’s perspective.

They are brutal because they have to be to compensate for the corruption of the system, which allows criminals to bribe their way out of prison. The new police commissioner says, “They can do anything because they transgress the law, and we cannot do a thing because it is the same law which stops us.” It doesn’t excuse the police atrocities, but rather, points a finger at how governments fail to provide alternatives, choosing instead to have the poor (and the police are poor, too, except for the higher-ups) destroy each other.

I do wonder whether First Worlders watching Satya will feel the same as Third Worlders do about the film. The poverty of the Third World is something that is very difficult to explain to people who haven’t seen it firsthand or experienced it. We’re talking generations of people who produce six or more children that they can’t feed, clothe, or educate properly, creating a cycle of poor nutrition, poor education, neglect, abuse, ignorance–it’s not surprising that some of these kids grow up to be murderers and rapists. Imagine coming from generations of hopelessness, of living like animals with no understanding or capacity to improve your lot in life, subsisting on garbage.

The poor are not lazy; many of them work themselves to exhaustion picking through garbage for food or doing menial labour or selling flowers or candies on the streets. But for all their work, they can barely survive, and no one cares because capitalism tells us that the value of a person is tied to their wealth. And it never gets better because it’s in the government and the elites’ interest to keep the poor stupid, ignorant, and uneducated so they can manipulate them like Bhau manipulates people into voting for him.

Early in the film, when Satya tussles with Bhiku in jail, he says: “Everybody gets a chance.” But what kind of chance is that, really, in the end?

As a final note: there is a fine line between poverty porn and telling the truth about conditions in the Third World, but I think Satya manages to critique the systems that perpetuate poverty without revelling in suffering and misery, and the characters in the movie are given humanity and identity beyond being just poor people. It’s a good film that deserves the accolades it received.