Note: This installment of the Tough Guys, Gangsters, and Delinquents in Asian Pop Culture series is one of my favourite films, Sympathy for Lady Vengeance. If you haven’t seen it yet, I urge you to watch it first because spoilers fall like diamond tears in this review. I suggest pairing it with The Last Seduction (not an Asian film but still a good noir). I also spoil Oldboy in this review, so be warned!

In the 1960s, pink films or pinky violence films became huge in Japan. They featured sexy women doing gangster shit and soft-core nudity, and many of the stories, especially the ones from Toei, were about women getting violent revenge for the shitty things that men put them through.

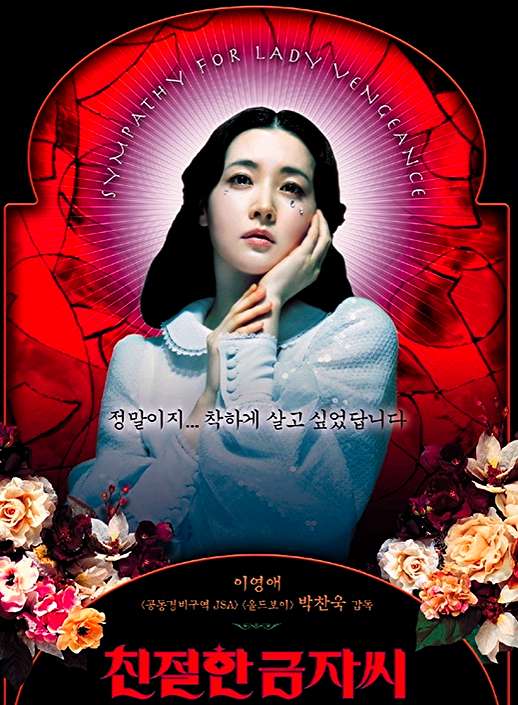

You could say that Sympathy for Lady Vengeance, the last in Park Chan-wook’s Vengeance trilogy, has its roots in pinky violence films; or perhaps more accurately, it’s an arthouse pinky violence film minus the overt eroticism. The gist of the story is that Lee Geum-ja (Lee Young-ae) gets out of prison, where she was incarcerated for thirteen years for the murder of a five-year-old boy. It turns out that with the help of a sympathetic police detective, Geum-ja has taken the fall for the actual killer–her older lover and former schoolteacher, Mr. Baek (Choi Min-sik)–who threatened to take away and harm her baby if she didn’t. Geum-ja has spent the entire thirteen years plotting her revenge and as she puts her plan into action, we’re subjected to contradictory accounts of who she really is–a witch, an angel, an innocent, a seductress, a mother, a killer–and how she’s affected and used the people around her.

On paper, Lady Vengeance sounds like a straightforward revenge story, but the story unfolds in unexpected ways. It’s not that it’s full of twists meant to impress you with their cleverness; instead, the unexpectedness is a result of inserting normal, real-life reactions into the violent world of gangsters and tough guys. This is something that Korean directors like Director Park particularly excel at in their films, and it reminds me of W. H. Auden’s poem “Musee des Beaux Arts”:

About suffering they were never wrong,

The old Masters: how well they understood

Its human position: how it takes place

While someone else is eating or opening a window or just walking dully along;

The poem talks about how miracles and great tragedies happen while normal life continues, “[w]here the dogs go on with their doggy life and the torturer’s horse / Scratches its innocent behind on a tree.”

A similar principle appears in Lady Vengeance: while all of the violence is going on, people are just living their normal lives around it and reacting like you’d expect, and it feels so jarring and darkly funny. For example, Geum-ja visits the parents of the murdered little boy, planning to cut off her fingers one by one until the parents accept her apology. Instead of focusing on this piece of gangsterism, the camera turns to the parents freaking out and trying to stop her, slipping on the blood as they try to clean the mess on their nice hardwood floor.

The Vengeance trilogy, as the name implies, is about retribution, punishment, and revenge. It’s a powerful theme that gets explored in many tough guy, delinquent, and gangster stories–whether it’s Ting cracking assholes on the head for stealing Ong-Bak or the triad boss needing to avenge his honour in The Mission–as it’s one of the consequences of living the violent life of the jianghu. The tragedy of redemption in these stories, though, is that these characters don’t know how to find it without causing more violence. And so, stories of vengeance either turn into a cycle of bloodshed that ends only when one person (or no one) is left or, like Lady Vengeance, the protagonists find out that there may be no redemption in vengeance after all.

When Geum-ja leaves prison at the start of the film, she’s offered a large cube of tofu. Eating it means that her sins have been wiped away and that she’s ready to start anew, but Geum-ja rejects the tofu to embark on her vengeance spree to take Mr. Baek down. She uses the women that she’s made friends with in prison to help her, and it’s here that Director Park forces us to reconsider how we’ve been conditioned to see female protagonists who are cast into the roles of femmes fatale and black widows in these types of vengeance films.

Is Geum-ja cold-blooded and ruthless? After all, she did kill one of her cellmates by poisoning her with bleach. Does it make a difference that the woman was a rapist and a bully? Could she be as kind-hearted as people believe she is? She even donates one of her kidneys to a cellmate. But then she manipulates and uses these recipients of her kindness to help her on her quest for revenge, including forcing former cellmate Park Yi-jeong (Lee Seung-shin) to seduce and marry Mr. Baek, causing her to endure years of marriage with an abusive man.

We should also note the importance of casting Lee Young-ae as Geum-ja. Lee is best known for her role in Jewel in the Palace, one of the most popular Korean dramas ever, and a drama that cemented South Korea as the top cultural influencer in Asia (and beyond). Lee became forever associated with her role as an optimistic, pure-hearted, virtuous, and strong-willed heroine who endures all kinds of hardships to become a doctor during the Joseon era (a time not known for women’s rights).

The closest Western star in terms of image and popularity is perhaps Audrey Hepburn (feel free to correct me if you can think of someone else). And so, the casting was a really shrewd and bold move that uses Lee’s image as a way to create expectations of Geum-ja that are eventually twisted and subverted. The men in the film, who could be stand-ins for the audience, especially want to believe in a fantasy image of Geum-ja as a woman who needs saving or as a femme fatale, even though Geum-ja is actually the tough guy of the film. She leaves prison like any gangster badass and gets her shit together just as you’d imagine any tough guy would. If she were a male character, her actions wouldn’t be subject to the same “Is she just pretending to be a nice person?” scrutiny; it’s something we would simply take for granted from a man hellbent on revenge, and I think it’s to Director Park’s credit that he makes this point in the film.

In many redemption stories, the protagonist redeems himself after killing off all the bad guys and saving an innocent (usually a woman or a child). At the end of Lady Vengeance, however, although she’s accomplished all of these things, Geum-ja doesn’t have the arrogance to simply walk away as though everything is now fine.

In the last scenes of the movie, she goes home with a cake that she’s baked to look like a cube of white tofu. It’s a reversal of the first time we see her: instead of being offered tofu, she’s the one offering the cake to Jenny, the daughter she had to leave behind and who is later adopted by a hippie-ish Australian couple. Jenny tastes a little of the cake, but Geum-ja, realizing that there may not be any redemption for her sins after all, only smashes her face into the cake and sobs.

The film’s narrator tells us that Geum-ja still doesn’t feel like she’s been redeemed, but that’s why the narrator likes her so much. It’s at this point that we realize that the narrator has been a grown-up Jenny all along. Jenny, who had wanted revenge herself against the mother who abandoned her but ended up forgiving her instead, is the only person who understands that Geum-ja is self-aware enough to know that she may never be worthy of forgiveness. And perhaps the story of Lady Vengeance is Jenny’s attempt to give her mother the peace and redemption she couldn’t find for herself.

In the Vengeance trilogy, Oldboy gets a lot of attention because of the incest and the over-the-top violence, but Lady Vengeance, without shedding as much blood as Oldboy, is more shocking in its violence because the vengeance in the story doesn’t just belong to tough guys like Geum-ja or gangsters, it’s regular people who, despite or because of their fear and morality, end up making a choice–let me stress that they are not driven by circumstance like some tough guys and gangsters but DELIBERATELY CHOOSE–to do terrible, terrible things in the name of vengeance.

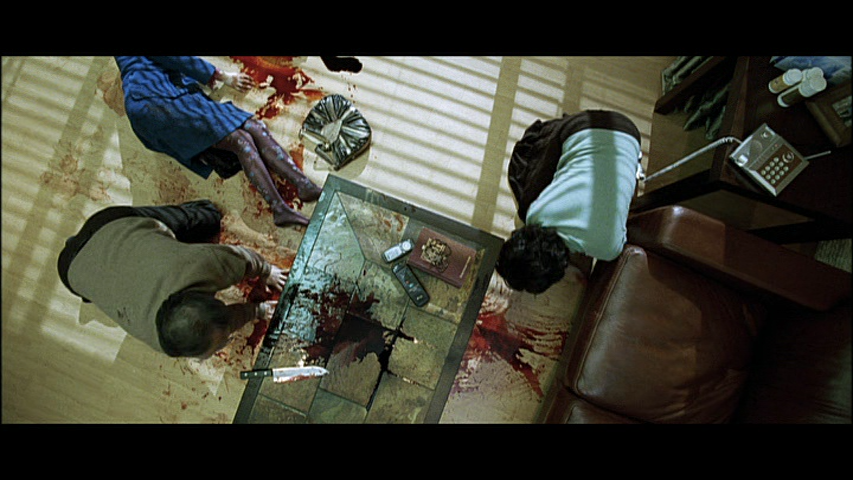

Geum-ja discovers that Mr. Baek has kidnapped and killed four other children, and with the help of the police detective who helped her fake her guilt, she finds the families of all the children and offers them a chance to take their revenge on Mr. Baek, whom she has kidnapped. The families–many of whom have fallen apart and suffered greatly after the kidnappings–choose personal vengeance over legal justice, and they are all given a chance to torture and kill Mr. Baek.

Despite this, there’s a messy humanity in this film that we don’t usually see in gangster stories, where we’re usually restricted to genre-specific points of view. We are constantly reminded that these are people with the same weird and random and petty thoughts that other normal people have, even during the times that we least expect to have them: the families compare each other’s wealth and suffering, take off their nice shoes so that they don’t get ruined by blood, and want Geum-ja to give them back the ransom money they paid.

The actual torture and killing of Mr. Baek is never shown, but our imaginations fill in the pain more effectively than any graphic violence. The film only shows the prelude to the violence, with the families sitting in quiet terror and anticipation in their raincoats holding their makeshift weapons, and the aftermath, with everyone helping to clean up and bury Mr. Baek. The cleaning reminded me of school in Taiwan–not that we killed anyone, as far as I know–but doing chores together was meant to teach us humility and cooperation, as well as establish a camaraderie between all of us.

Mr. Baek’s torture and death is also reminiscent of other ancient rituals where sacrifice and killing restore the balance to society by satisfying blood feuds and reforming broken bonds. It made me think of both Julius Caesar’s assassination in Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar and the stuff that happens in Shirley Jackson’s short story “The Lottery”.

The bond that forms between these avenging families is further strengthened by the cake that they eat together after they dispatch Mr. Baek. If you’ve watched a lot of Asian gangster films, by now you must have noticed how important meals are to solidifying brotherhood, and this harkens back to a past where meals had a ritualistic purpose connecting social groups together. I’ve also written about the importance of funeral foods for the A.V. Club (please pardon me for linking my own article like an asshole) where I trace how eating sweet foods after funerals (or a death) is linked to ritualistic cannibalism meant to honour the dead (in this case, not Mr. Baek but the dead children; note that one of the parents starts singing “Happy Birthday,” as though they were at a children’s party) and again, is a way to establish group connections.

And speaking of bonds in this film, I’ve spent the previous articles talking about brotherhood, and this is the first film that shows what real sisterhood looks like. As former inmates, these women are no longer accepted in mainstream society, thus they’re not expected to follow the rules that govern “decent” women. They have no need to fall into the typical “sisterhood” that revolves around shopping and crying over men, but can express their friendships in the same way that men do.

They are loyal to Geum-ja as though she were some kind of gang boss, and in fact, she really is one in all but name. She gets rid of the other women’s problems for them but also expects them to aid her in achieving her goal. Out of all the gang bosses that I’ve written about so far, Geum-ja may be the best one, not because she is the harshest and most violent–a boss like that doesn’t keep his followers very long–but because she understands best what inspires or frightens people. She’s kind-hearted Geum-ja whose face shines when you look at her, but she’s also a killer and brilliant strategist who will do anything necessary to get to her goal.

Now that’s a true boss.