Note: This is Part 3 of my Tough Guys, Gangsters, and Delinquents in Asian Pop Culture series. I’m going back to Hong Kong to another influential film that inspired classic gangster iconography and shootout tableaux, The Mission. Not to mention, director Johnnie To is one of the biggest influences on my own work as well. As usual, spoilers fly like bullets in this post!

Johnnie To’s first masterpiece The Mission came out in 1999 as an answer to all the Hong Kong gangster movies romanticizing the triad lifestyle in the wake of Young and Dangerous. It’s not that triads hadn’t been romanticized before, but Young and Dangerous and its sequels brought it to another level by making it look like fun boyhood adventures.

The five killers in The Mission definitely aren’t in the business for fun and laughs. They’ve all been hired to protect a triad boss, Lung (Eddy Ko), who’s being targeted for assassination by an unknown enemy. Lung’s brother, Nam (Simon Yam), recruits hairdresser Curtis (Anthony Wong), bar owner Roy (Francis Ng), Roy’s protégé Shin (Jackie Lui), snack lover James (Lam Suet), and pimp Mike (Roy Cheung).

To didn’t have a lot of money to make this film; it went into production just as the Hong Kong film industry went into a slump, defeated by piracy (thanks to the triad!) and a slew of increasingly desperate and crappy films. To took only nineteen days to film and wrapped up the entire thing in a month, but the one place that I think the lack of funds shows is in the soundtrack (I’m really not fond of the music production and wish someone would remix it or something).

On paper, without the exciting business of heroic gangster protagonists, The Mission doesn’t seem like much: the bodyguards/killers spend most of their time hanging around being bored before getting into gunfights, which is the opposite of what Young and Dangerous makes triad life out to be. Don’t get me wrong: The Mission is extremely watchable, a hundred times more than any Young and Dangerous film. It’s incredible that it manages to pull this off even as it makes gang business feel about as enjoyable as working at a bank.

This is not to say that there isn’t any action or fun (for the audience) in the movie; the set pieces are amazingly choreographed and have that unique To style where the camera moves around figures like they’re in a tableau, and impossibly cool shots.

To’s signature shots in narrow spaces and alleys are also already present.

But it’s been said that PTU (another To film which I wrote about for the AV Club–sorry to plug it here like an asshole) is the most exciting film made where people just walk around, and I guess that would make The Mission the most exciting film made where people just sit around and wait.

To uses this downtime to build the camaraderie–not just among the bodyguard/killers, but even with their enemies later in the film. When the bodyguards finally find the assassins’ lair, they manage to take it over after a protracted gunfight between Mike and the sharpshooter assassin. Once they’re in and waiting for instructions, they just basically settle in to hang out with each other and share some cigarettes even though they’ve just tried to kill each other.

Mike and the sharpshooter even exchange smiles of acknowledgement (notice they even have similar injuries on their faces) of each other’s skill. No hard feelings there, it’s just real recognizing real.

However, the camaraderie among the bodyguards hits an early rocky patch when Roy is left behind at Curtis’ command when the group is ambushed by a sniper as they take Boss Lung to his car after work. This is the conflict that foreshadows the eventual problem that will test one of the most important tropes of the gangster genre: brotherhood and loyalty.

In Part 2 of this series, I touched on the idea of masculinity in wuxia and delinquent stories as not just being about violence, but about brotherhood and friendship. You’re not a man because you punch (or in this case, kill) people, you’re a man because you’re not a coward or a traitor.

But betrayal comes in different forms, and The Mission uses the job for Lung as a catalyst for exploring them. Do you prioritize the mission (and the boss) over a brother? Or are the bonds of brotherhood more important than anything else? Which do you betray and still consider yourself a man?

Curtis, the most cold-blooded and professional of the group, is the one who has to face the complexities of different loyalties most. Anthony Wong plays Curtis as unreadable and aloof in contrast to Francis Ng’s Roy, who is hotheaded but warm and emotional.

Let me explain the kind of Hong Kong guy Roy is: one time, I was hanging outside a 7-11 late at night in Kowloon (I had a busy life pre-kid). This shirtless dude got into a loud fight with a much bigger dude, and he called out to a friend of his across the street for help. The friend hopped over the guardrail and immediately got hit by a car, but he somehow used it as momentum for launching himself in the air to land with a punch on the big dude. That is the kind of man Roy is, and Roy would never leave anyone behind no matter what. He’s the one who tries to plead with Curtis when, after the assassins have been dealt with, the real problem comes up: Shin has been having an affair with Lung’s wife (Elaine Eca Da Silva).

This is a betrayal of the underworld’s code of honour: you never mess around with another person’s wife or girlfriend. Nam wants Curtis to kill Shin, and considering that Curtis chose the mission over Roy in the beginning, it’s pretty clear to the other killers what his priorities are.

The other killers also struggle with their own conflicting loyalties: Mike decides to help Roy sneak Shin to Taiwan on a boat, only to almost kill him at the last minute because Shin’s disappearance would mean that Curtis (and everyone else) will die. Shin himself decides not to leave; his loyalty to his brothers outweighs his fear of death.

Even enigmatic loner James goes out of his way to try to convince Lung to let Shin go, even though he knows it’s hopeless, and he’ll have to bear the responsibility for Shin’s mistake. I thought it was really moving to see him awkwardly practicing what he’d say to Lung because he’s clearly a man who isn’t used to begging for anything.

These decisions reveal the most important thing about masculinity and brotherhood that often gets overlooked: sacrifice. Without sacrifice, there is no brotherhood and there is no masculinity beyond mere violence. Stories about the jianghu, gangsters, and delinquents almost always involve sacrifice of some sort, which I think partly explains why they continue to endure. There’s something about the idea that someone would give up their life (or at least their happiness) for others that really resonates with us on a primitive level, and I think it’s related to what anthropologists call “parochial altruism”, which is the sacrifices members make for their group. Tribes can’t survive without parochial altruism, and I think its importance is still lurking somewhere in our brain.

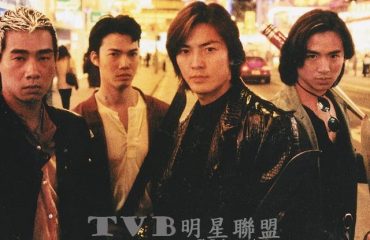

Although the characters roughly fall into familiar tropes, they never seem clichéd. A lot of it has to do with the actors, who all come from the generation of great Hong Kong actors that were born in the 1960s. Even though there isn’t a lot of dialogue, and the conversations themselves are pretty banal, each character feels completely fleshed out (with the exception of one, whom I’ll get to later).

Considering the tight shooting schedule and To’s off-the-cuff method (many of the scenes were improvised, with the actors not even aware of when shooting was done), it’s really amazing how well the characters are realized. And even though the movie doesn’t intend to romanticize gangsters, with actors like these, it’s extremely difficult for the characters not to look cool.

I don’t know what was in the dimsum during that time, but that generation defined coolness and a kind of down-to-earth manliness in a way that no other generation has since been able to match or live up to. I mean, look at them: they’re just so effortlessly badass, even though no one is conventionally handsome except for Francis Ng (whose acting convinces you that his character isn’t good looking) and Simon Yam, whose good looks drip with venom in this film.

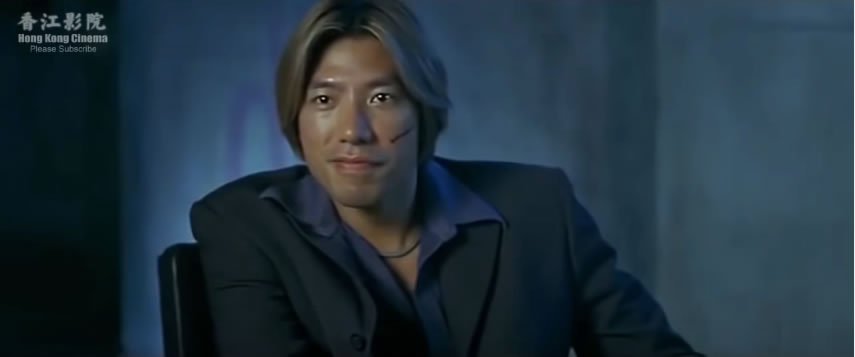

Simon really stands out even in his small role, and I think the best way to describe his performance is this: a long time ago, I read this article where a retired FBI psychologist who’d worked with captured serial killers was describing his interviews with them. He said that one guy was so charming and likable, he eventually began looking forward to their interviews until one day, he realized that he was laughing along with the serial killer as the dude described the horrible shit that he’d done.

When Nam visits Curtis at his salon to get him to be one of Lung’s bodyguards, he mostly talks about a bad haircut he’s had, and yet without really doing much–it’s all in the eyes and the volume of laughter–he manages to convey unpredictable violence and menace underneath his good humour and charm. If you’ve ever been tormented by a charming, sociopathic boss, you’ll be terrified right away.

Compared to him, Lung seems like a much kinder dude (especially since Eddy Ko looks like that one uncle who slips you a consolation red packet when you fuck up a piano recital) who gives an ex-bodyguard some extra cash even though the dude was a coward. Lung even makes coffee for his bodyguards and is really generous to them, but in the end, it turns out that he’s the scariest one of all when he has his own wife killed.

Lung’s wife is the only one-dimensional character in the movie; she doesn’t even have a name and basically serves as a plot point. We only ever see her leaving or arriving; she doesn’t really belong in this world and her presence tests the loyalties that these men need in order to keep the group going. Although there are strong female characters in other wuxia and delinquent stories, women still often serve as a way to shake up loyalties among men.

There’s always a tension in these stories when a woman becomes a part of a man’s life–will he choose his brothers or his girlfriend/wife? (Incidentally, you don’t usually see this conflict when it comes to female characters; it’s almost assumed that the chick will stand by her man because sisterhood doesn’t exist the way brotherhood does.) It just seems odd to me that brotherhood is so strong that men will die for each other but then once a chick arrives, anything could happen.

With that said, only Shin, the youngest of the bodyguards, actually falls for Lung’s wife’s seduction. I think this is where the movie makes a wrong step because we find out that she’s hit on almost everyone else, and they all managed to resist her. It takes away the gravity of Shin’s betrayal by placing some of the blame on the wife for being slutty. I guess that’s how we’re supposed to stay sympathetic to Shin instead of thinking that he deserves to be shot for being a horny maroon, but it weakens the conflict and drama.

In real life, there are chicks who have a place among delinquents and gangsters aside from roles as family, girlfriends, or temptresses. For example, Olive Yang, who died just this past July 13, was a drug warlord who ruled the Golden Triangle. Although we haven’t really seen that reflected in pop culture very often, every so often, something squeezes through, like Portland Street Blues, which I’ll be writing about next week.