Note: if you haven’t seen Mr. Vampire before, I urge you to watch it now before you read this because there are massive, massive spoilers here, and I wouldn’t want to spoil your enjoyment of this fantastic film. If you haven’t yet, you might want to read the rest of the Tough Guys, Gangsters, and Delinquents in Asian Pop Culture series.

As a kid, my playmates and I used to play games pretending to be characters from Mr. Vampire. When I grew up, I found out that it wasn’t just me, but there were kids all over the world whose childhoods were equally affected by the film. Now that is influence.

As its name suggests, Mr. Vampire is a movie about vampires–not the European ones, but jiangshi, the hopping undead that’s both vampire and zombie.

Jiangshi history is really entertaining; the folktales probably originated as far back as the Ming dynasty, although they became more popular in the Qing dynasty. According to this Taiwanese history teacher, the stories possibly come from when they used to transport corpses over long distances: the corpses would be stood upright, their arms tied to a pair of bamboo poles, and carried between two bearers. The bouncing movement of the bamboo poles as the bearers carried the corpses made it look like a bunch of undead hopping around, especially since they traveled at night. Thus the legend of Taoist priests transporting corpses via supernatural means was born.

I have to add here a story from my mother about her country childhood in Taiwan: she used to live in a village so remote that whenever someone died, it was some dude’s job to bike the corpse to the nearest town with a morgue. They would drape the corpse over the back of the corpse transporter and arrange it so that it still looked alive and not freak too many people out.

My mom remembers waking up in the middle of the night to watch them load up a corpse once, and the transporter noticed that she was watching and, as a prank, nudged the corpse so that it looked like it was coming alive.

I’m writing this because I’m sure that at least a couple of the corpse bearers in the Ming and Qing dynasties had a sense of humour and played tricks like that on people that they encountered.

Jiangshi are often shown wearing Qing dynasty government official’s robes, and I can’t help but agree that there are few things more terrifying than an undead bureaucrat. The Taiwanese history teacher suggests that the reason for this is that Ming government robes aren’t as fancy as Qing ones, which add that extra undead glamour. However, considering how much the Qing dynasty was loathed, I agree with theories that anti-Manchu sentiments probably have a hand in the jiangshi outfits, too. For those who are unaware, the Qing rulers were of Manchu ethnicity, which didn’t sit well with the majority Han people, and it makes sense that the Qing government would be represented by a qi-draining and slowly rotting undead corpse.

What’s interesting is that this anti-Qing aspect links jiangshi to the triad societies, as the oldest societies have their roots as rebels trying to overthrow the Manchus. And that is my flimsy-ass reason for including Mr. Vampire in this Tough Guys, Gangsters, and Delinquents in Asian Pop Culture series, although the movie does have tough guys (well, one tough guy and two comic relief semi-tough guys).

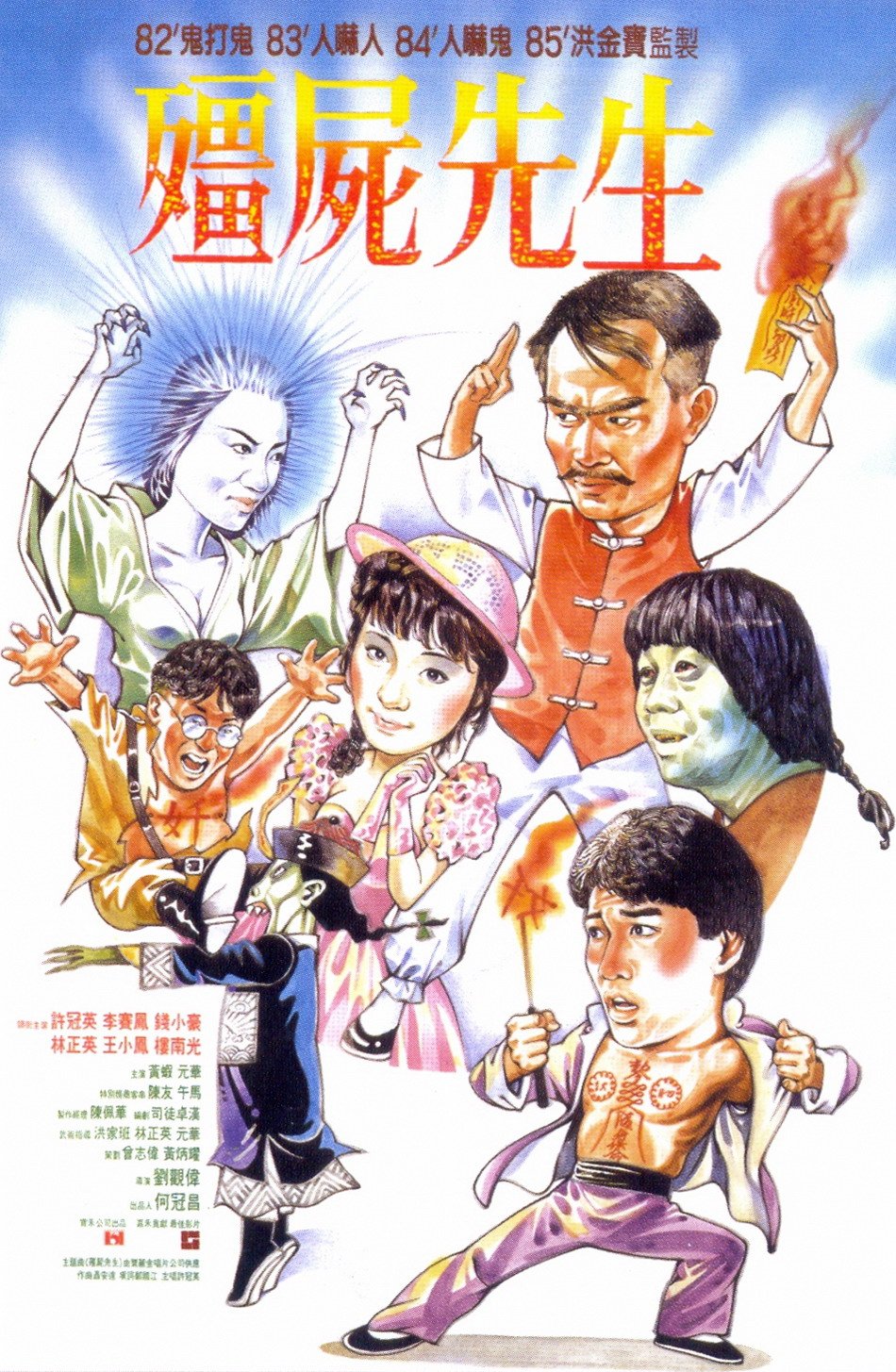

Mr. Vampire isn’t the first time that jiangshi made an appearance in Hong Kong film, that honour goes to the 1980 film Encounters of the Spooky Kind, starring Sammo Hung. Encounters of the Spooky Kind was reasonably popular enough to spawn a sequel, and more importantly, inspire Sammo Hung to produce Mr. Vampire in 1985, which was a huge hit that kickstarted a jiangshi film trend and provided fodder for kids’ games all over the world.

The movie blew past its low budget during filming, most likely because of shooting locations–they filmed in both Taiwan and Hong Kong–and makeup for the jiangshi and a female ghost. It was a blessing in disguise that they didn’t have enough money to spend on additional special effects, which would have aged the film terribly. The special effects makeup is bad enough, and even in 1985, the jianghsi and the female ghost never looked scary. Instead, what Mr. Vampire does–what makes it a classic that is still watchable in 2017, thirty-two years after it was first released–is rely on fantastic comic timing, intriguing yet culturally familiar mythology, and amazingly choreographed martial arts fights and stunts. There’s a breeziness and almost a sense of improvisation that characterizes the best Hong Kong films of that era, where all the comedy and the action flow together naturally.

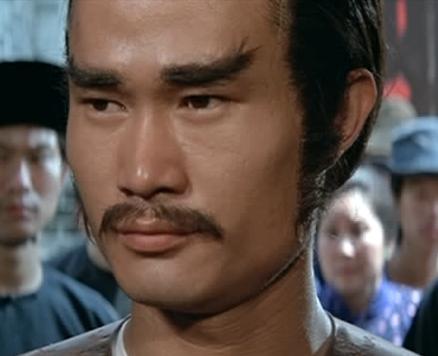

Master Kau (Lam Ching-ying), a Taoist priest, and his two mischievous assistants Man-choi (Ricky Hui) and Chau-sang (Chin Siu-ho), are tasked with the reburial of wealthy Mr. Yam (Huang Ha)’s father in the hopes of improving the family’s fortunes. As they begin the process, Master Kau realizes that the feng shui master who advised the original burial has given the family bad advice. The resulting curse and the fact that Mr. Yam’s father died with his breath caught in his throat means that he’s become a jiangshi.

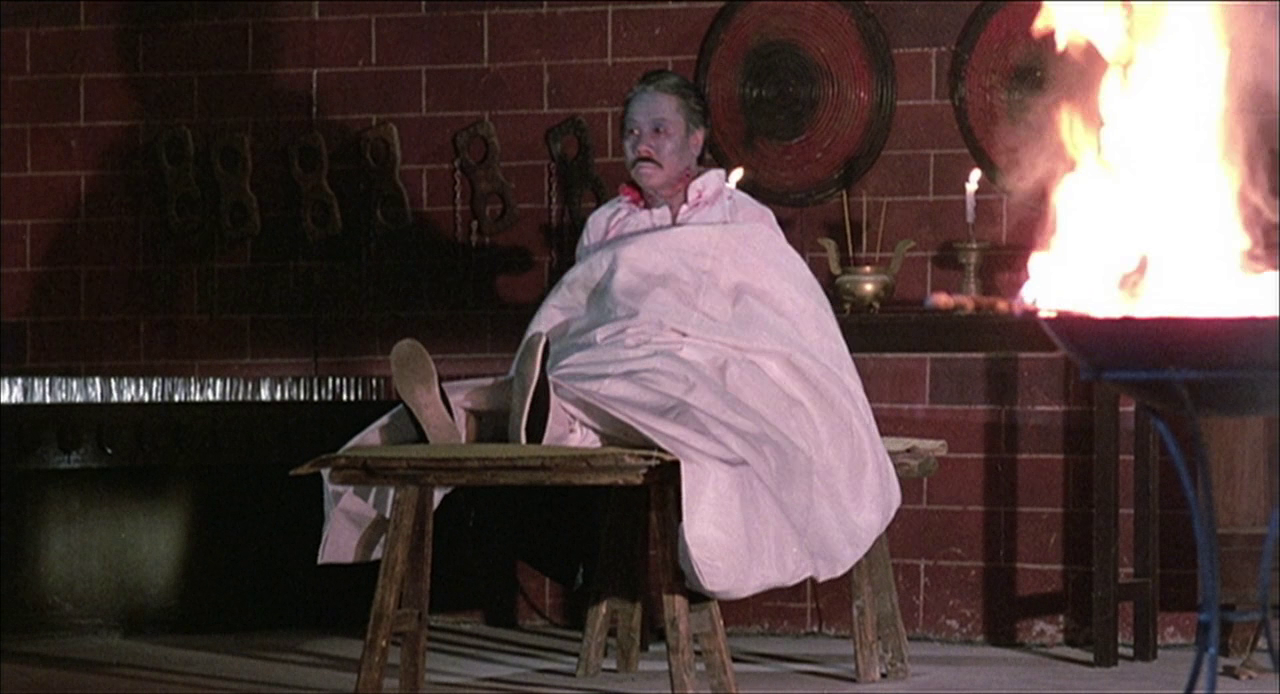

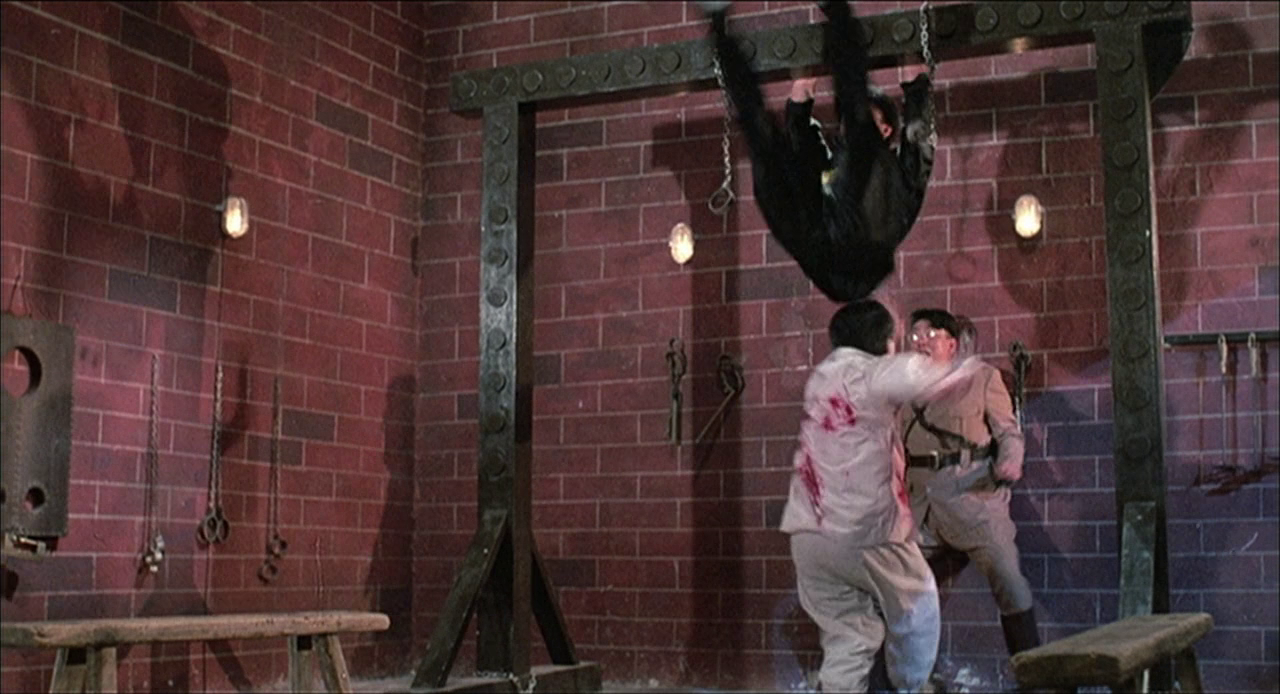

Despite all the precautions that Master Kau makes, the jiangshi rises to kill Mr. Yam and terrorize Mr. Yam’s daughter, Ting-ting (Moon Lee). Mr. Yam himself becomes a jiangshi and the scene where he comes unalive in a jail/torture chamber is one of the two absolutely brilliant set pieces in the movie.

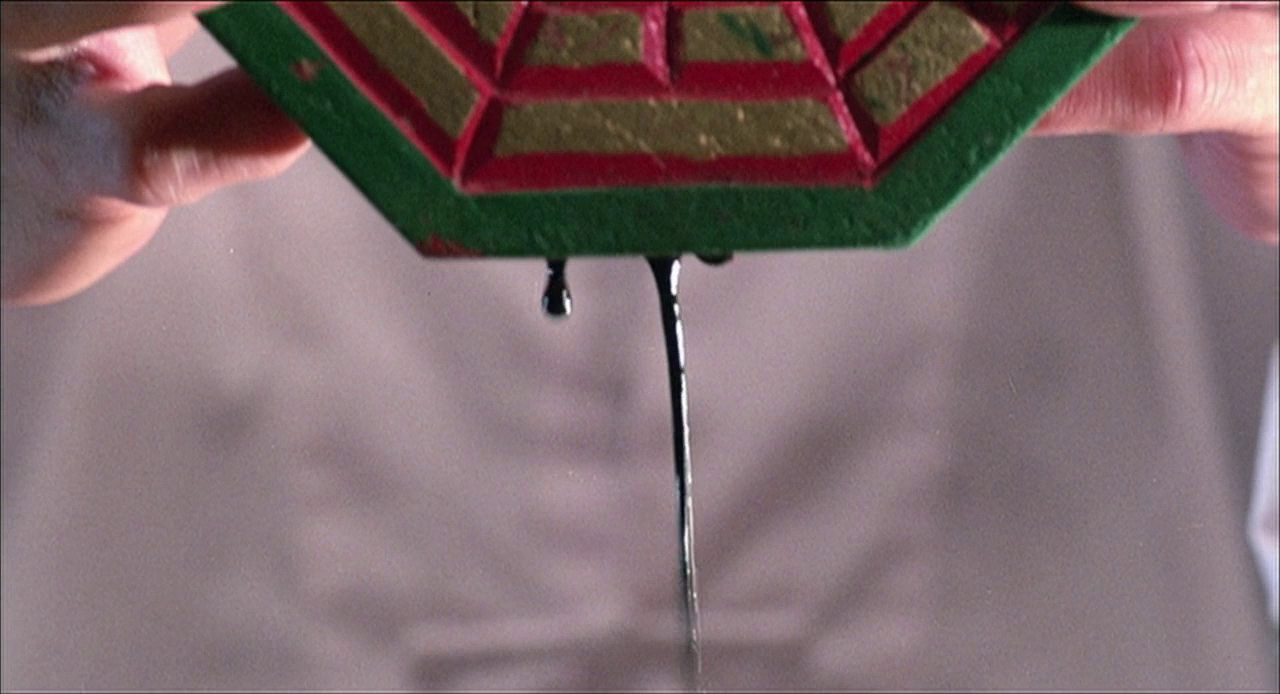

Believing Master Kau to be responsible for Mr. Yam’s death, Ah Wai (Billy Lau), Mr. Yam’s nephew and the head of police, threatens to torture a confession out of the Taoist priest before locking him up in a jail cell. When Chau-sang goes to rescue his master, Mr. Yam’s corpse rises and attacks them, with Master Kau using the chicken’s blood and ink to write a talisman to freeze the jiangshi.

Ah Wai comes back into the jail because of the ruckus, removes the talisman, and the shenanigans resume with Ah Wai and Chau-sang being chased around by the jianshi while Master Kau stays locked helplessly in his cell.

The entire sequence is a non-stop series of gags and stunts, with the young Chin Siu-ho, who would later famously face off with Jet Li in Fist of Legend, showing off his acrobatic skills. Seeing how fresh-faced and talented Chin used to be, it’s a little sad to watch him now with the knowledge that he’s a pervert and a deadbeat dad.

Ricky Hui’s scene-stealing skills also gets him his own subplot when he is injured by a jiangshi and almost becomes one. Hui is such a natural comedian that it’s incredible he started out as a journalist, of all things, and Mr. Vampire owes a lot of its laughs to his performance.

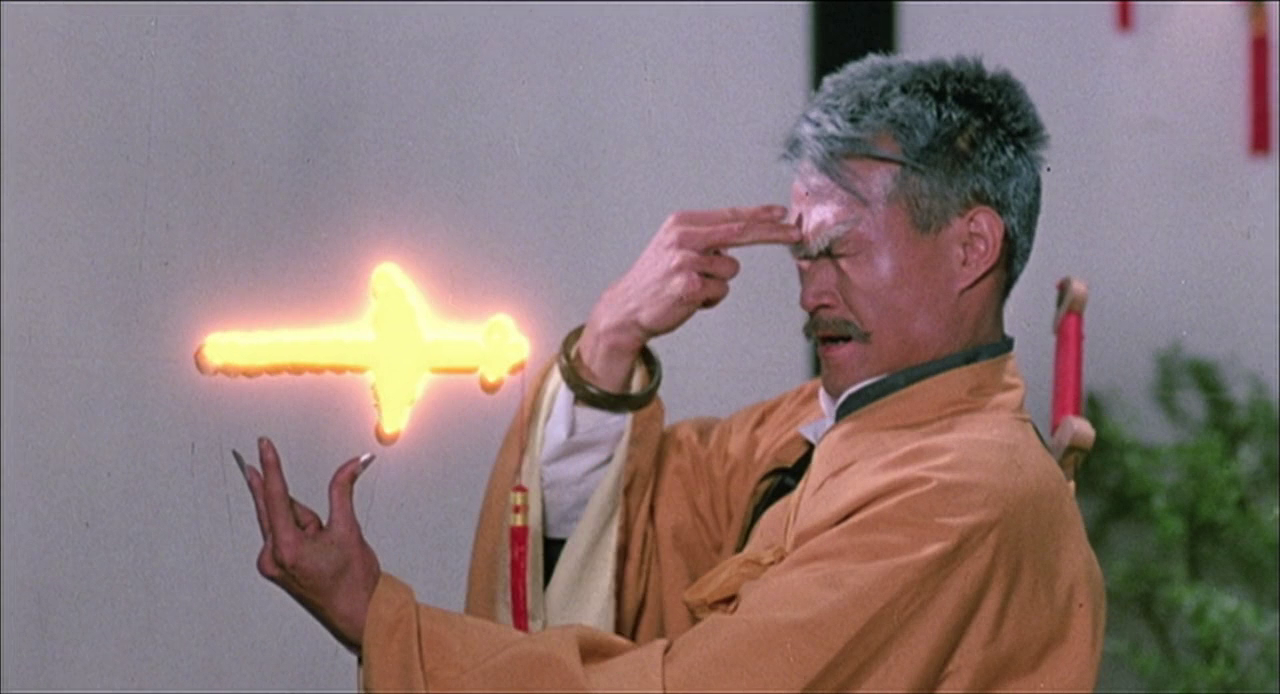

Eventually, Master Kau manages to get himself out of his cell, and the moments in this sequence and elsewhere in the film where he uses things like bagua mirrors, yellow paper talismans, sticky rice, and string soaked in chicken blood and ink to defeat the jiangshi are just as mesmerizing and thrilling as the action sequences. When I was a kid, there was something so satisfying about collecting the same items from our house (minus the chicken blood) and using them in our games. I should also mention here that, being light-skinned hence corpselike, I was always relegated to the jiangshi role, which is probably why my knees are so busted now from all the hopping.

The movie isn’t exactly kid-friendly–there’s an entire subplot where Chau-sang is seduced by an amourous ghost that does have a payoff at the end–but there are so many moments that seem tailored for kid interaction. Jiangshi find their victims through their breath, so holding your breath is one way to prevent them from attacking you. There are a couple of scenes like this in Mr. Vampire, and I’m sure every kid watching also held their breath to see if they could survive a jiangshi.

The final, climactic showdown towards the end of the film is fantastic, as well, tying up all the Chekhov guns and subplots of the film. At the beginning of Mr. Vampire, Man-choi and Chau-sang get into trouble for messing with the jiangshi that Taoist priest Four Eyes is transporting across the country for burial. At the end, these same jiangshi and Four Eyes show up to help out, along with Jade (Wong Siu-fung) the female ghost who has seduced Chau-sang. Everything locks into place, all the storylines thankfully converge, and not a single movement or action is wasted. The ending, despite being abrupt (typical for Hong Kong action films of that era) is still completely satisfying.

Mr. Vampire made a star out of Lam Ching-ying, whose image is probably seared into the minds of countless people with his iconic performance a tough unibrowed Taoist master with a heart of gold. But Lam actually had a really fascinating career in the Hong Kong film industry before that, including a stint as Bruce Lee’s close personal assistant at age nineteen and as one of the action choreographers on Bruce Lee’s major films. He also played the tragic, kindly Uncle Wah in Sammo Hung’s Painted Faces, a role I can’t think of without wanting to give him a hug. Lam was only thirty-three when he made Mr. Vampire, and he died of cancer just over a decade later. He was a great performer and seemed like a pretty good guy.

If you’ve been following the Tough Guy, Gangsters, and Delinquents in Asian Pop Culture series, you’re probably wondering whether I can still bust out some Marx even in a horror comedy film with hopping jiangshi, and the answer is yes because the whole jiangshi problem in Mr. Vampire is caused by wealthy people being assholes. Mr. Yam’s father forced the feng shui master to sell him a lucky burial ground, which is why the same master gave bad advice to Mr. Yam in revenge.

There’s also an obvious correlation in the film between Westernization and wealth, especially in one scene in particular set in Hong Kong’s Luk Yu Tea House (yes, the very same one where a tycoon was gunned down by a contract killer on orders of a triad boss). Mr. Yam and Ting-ting are having Western-style tea with Master Kau and Man-choi, who have no idea what coffee and egg custard tarts and even how to eat them. The scene pokes fun at “local boys” imitating the Westernized manners of the gentry, which may be significant in light of the film’s setting.

The movie is set during the early Chinese republic, just after the fall of the Qing dynasty, during which the founding father (emphasis on the fathering, if you know what I mean) of modern China, Dr. Sun Yat-sen emphasized both rejection of European imperialism but also, rather confusingly, modernization through Westernization.

I have to say that this struggle around modernization and nationalism continues to have an effect to this day because much of it centres on the question: how did China, a 5,000-year civilization with so many technological and cultural advances, fall so far behind? And, just as importantly, what could it do to catch up?

The answer to the first question is very complex and involves many different factors, some of which are just due to sheer bad luck. As for the latter question, to many, the answer was (and still is) to imitate the West, conflating modernity with Westernization.

From the early Chinese republicans all the way to the current Communist Party, that meant a rejection of many traditional Chinese values and teachings, from Confucianism to Taoism. Like in many postcolonial countries, that meant that in China, how Westernized you are dictates how high your social status was (and is). Many rural folk weren’t caught up in the wave of Westernization, and thus were often mocked by the elites for being bumpkins or uneducated (sounds rather familiar, doesn’t it).

Considering that the people responsible for creating Mr. Vampire were not of that elite class, I wonder if it’s a coincidence that it’s these very same Westernized people who are responsible for the appearance of jiangshi–created when the natural order is disturbed and traditional customs aren’t respected or followed. Nor does it seem like a coincidence that it’s humble salt of the earth like Master Kau, with their knowledge of traditional remedies and techniques, who can effectively respond to jiangshi and other supernatural threats.

Just in case there are some hurt feelings out here, Mr. Vampire doesn’t say that all Westernized elites are bad: Ting-ting doesn’t die, mostly because she’s innocent and a woman, thus can be protected by Master Kau et al.

I should make a note here that the other main female character is Jade, who, in contrast to Ting-ting’s virginal innocence is a sex-hungry ghost who will eventually drain Chau-sang’s qi if given the chance. The sexually rapacious female ghost who uses up men has long been a Chinese folklore staple, speaking to thousands of years of male insecurity over sexual performance and blaming male sexual desire on nefariously seductive women, but it’s interesting that while Ting-ting is helpless, it’s Jade who saves Chau-sang’s life when she swoops in to protect him from Man-choi who has turned into a jiangshi even though Master Kau might destroy her. Jade was originally supposed to die, but the filmmakers decided it was more romantic to let her agree to give up Chau-sang and leave, making her a redeemed villain with a pretty interesting arc.

The jiangshi films that followed Mr. Vampire never reached the original’s fun and brilliance, which is to be expected as most of them simply rehashed the same formula with often terrible gimmicks like jiangshi children (what is a child doing wearing a Qing official’s robes?). But I would venture to say that most of Mr. Vampire’s fans probably don’t care. We learned everything we needed to know about fighting jiangshi in the original film, and we’re good to go.