Note: And now we’re up to number six in my Tough Guys, Gangsters, and Delinquents in Asian Pop Culture series! This week’s entry, Ong-Bak, is our first tough guy who isn’t a gangster or a delinquent, but is a classic archetype of the tough guy who stands up for the weak and vulnerable. As usually there are as many spoilers as there are slow-motion scenes in this film.

In 2003, seven years after Young and Dangerous made it cool to look like a Sanrio character, Ong-Bak came out and made it possible for any buff, Thai-looking dude to open up a muay thai studio anywhere in Asia.

How much of an impact did Ong-Bak have? Four years after the movie came out, I was working at an upscale furniture retailer targeting expats. I had to visit the warehouse with my colleague, Dev, who had just moved from New Delhi a couple of months before, and when we opened it up, we found ourselves looking at row after creepy row of decapitated Buddha heads (I really don’t think white people have gotten over the time in their history when they displayed heads as part of their residential decoration).

Dev and I turned to each other and said, “Ong-Bak!” and suffice to say, we got out of there before Tony Jaa showed up and knocked us out at the same time with a kick split.

For those of you who haven’t seen this film, Ong-Bak is about Ting (Tony Jaa) going after some assholes who have taken the head of his village Buddha statue, Ong-Bak, causing them to suffer a drought, so you can understand their sense of urgency.

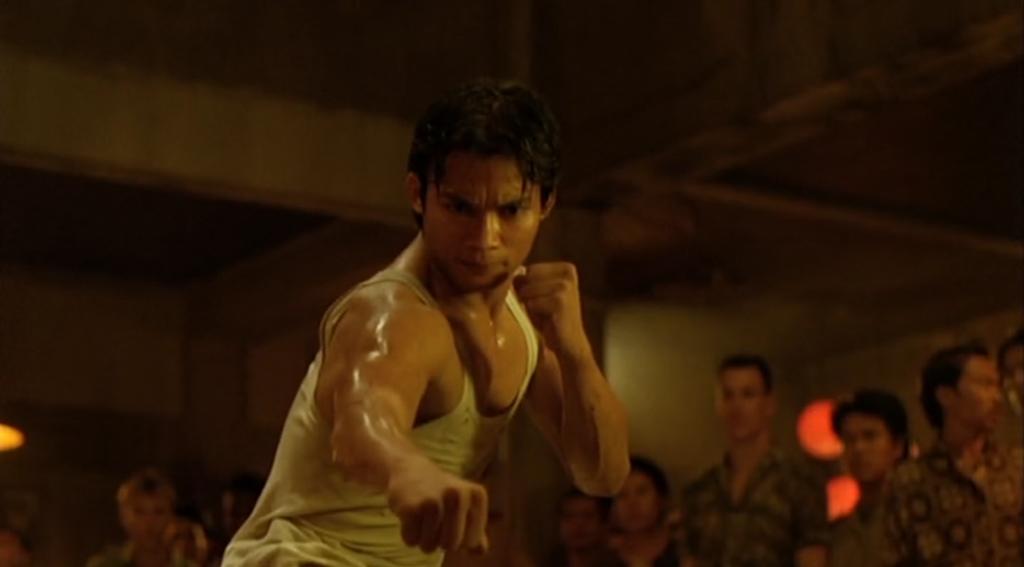

Ting follows them to Bangkok, where he hooks up with his petty conman cousin Humlae (Petchtai Wongchumlao), who’s taken on the more sophisticated name “George”, and Humlae’s sidekick, Muay (the absolutely adorable Pumwaree Yodkamol). Ting accidentally gets involved in underground fighting (as you do) and eventually takes Ong-Bak’s head back from the asshole crime lord Komtuan.

I’ll just quickly make a note here that people freaked out over Komtuan because he’s got a hole in his throat and uses a portable voice amplifier to talk. I didn’t really get why that was so weird because one of my teachers in school had the same thing. That’s all.

Ong-Bak’s plot is a variation on the tough guy from the countryside narrative: a country boy goes up against more sophisticated and powerful opponents with only his farm-honed strength, innocence, and goodness. It’s basically the story of every folk hero.

Although delinquent and gangster stories may have individuals who are rich, their worlds are usually set within the urban lower income society. Despite this, there isn’t usually much focus on class conflict. The tough guy from the countryside narrative, however, IS usually explicitly about class conflict so it’s really no surprise that a lot of Third World and developing countries with huge income gaps love folk heroes like this.

I understand why: I’m already quite privileged and even I feel helpless and full of anger against the bullshit that the wealthy perpetrate in Asia, especially in Third World countries. It’s clear that the wealthy loathe the poor–just watch how they interact with servers and domestic helpers–and if someone like me can feel angry, imagine the rage and resentment that the poor and oppressed feel.

Unfortunately, in real life, the folk hero narrative is often exploited by politicians, who claim to represent the poor and promise to fight for their rights. These people are always liars. The Philippines alone elected an actor who was famous for his folk hero roles and not surprisingly, he pillaged the country. This isn’t restricted to Third World countries, by the way, as you can see with what’s happening in the US and many European nations.

The tough guy from the countryside narrative also usually focuses on another source of conflict: the urban versus the rural. In Ong-Bak, the rural folk are shown as being in touch with their culture and traditions: simple people who are at peace with themselves despite their poverty.

On the other hand, the urban Bangkok residents are shown as having given themselves over to drug abuse, murder, theft, sex trafficking and prostitution, and so on. Their sacrifice of their traditional values for capitalist ones makes them miserable and shitty people who don’t value love and have lost compassion for others.

In Ong-Bak, the urban folk are the ones who betray their culture and even their identity as Thais: they disrespect religious and traditional customs like cutting off Ong-Bak’s head or Humlae’s refusal to be ordained as a monk (part of the Buddhist tradition in Thailand is for men to enter monkhood for a short period of time). Not only are they willing to sell off their culture, they also sell out their dignity to badly-wigged Japanese and Western foreigners, who say stuff like, “Thai people are weak! This is why Thai women come to my country to become hookers!”

I’d like to stop here for a moment because some of you may only now be realizing that many of the Asian martial arts folk heroes end up fighting Western and Japanese people a lot (just look at Jet Li’s oeuvre).

Ong-Bak illustrates its effects a little crudely, but the history of colonization and imperialism in Asia means that white men feel superior to the local men and entitled to the local women (and frequently children), an attitude they frequently demonstrate in the same terms as the white antagonists in Ong-Bak do. And then there’s the Japanese occupation, which brought misery to millions of people, that Japan has never really shown remorse or proper compensation for. The role of the folk hero is to show that morally bankrupt urban elites may suck up to foreigners, but the tough guy from the countryside isn’t afraid of challenging exploitation and imperialism because he has pride in his culture.

The way foreigners use local women (and children) is something that I think any Southeast Asian is familiar with: growing up in Manila, I was used to seeing white men flaunting the women and children that they were paying to have sex with. I’m not going to blame this all on foreigners, but it has been clearly documented that sex trafficking of vulnerable children, and especially girls, spiked in Southeast Asia during the Japanese invasion and then became an entire US and local government-approved industry during the Vietnam War. (Similar to the increase of trafficking in Japan and South Korea because of the US bases there.)

So, until militarized prostitution and Western sex tourism disappear and Japan properly acknowledges all the shit that it’s done, we’re going to keep seeing scenes like this pop up in all folk hero narratives because audiences, who otherwise have no outlet for their anger, need the catharsis and satisfaction of seeing the hero deliver some violent retribution.

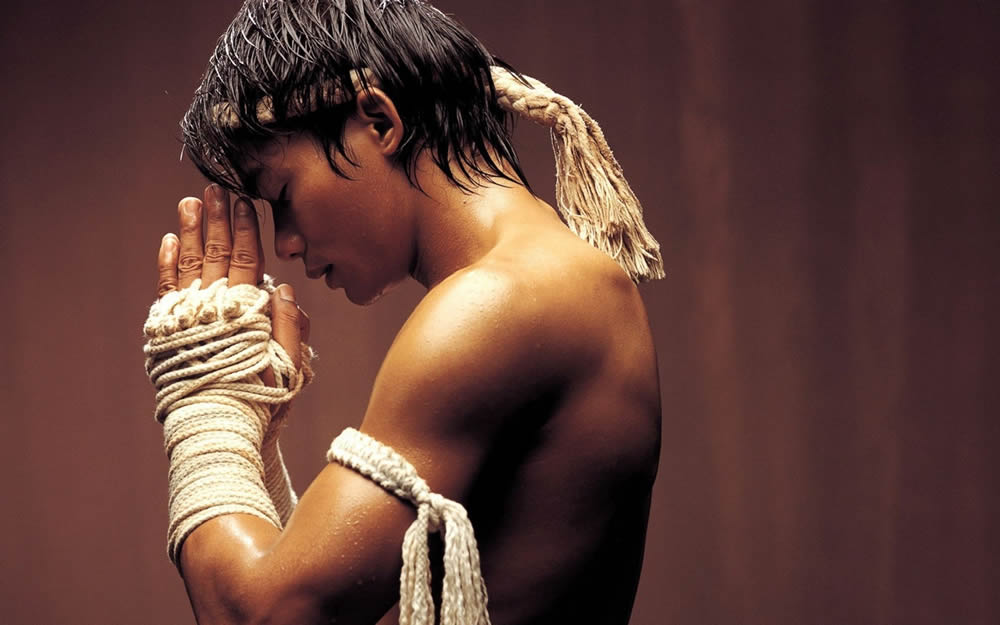

In Ong-Bak, to add to that satisfaction, Jaa is so clearly from a rural area himself, with the way he speaks and carries himself–not to mention his dark skin, so unique in Southeast Asia where most celebrities are light-skinned and/or mixed race because of colonial mentality despite most of the population looking like Jaa.

As popular as folk hero narratives are, they’re not always guaranteed hits like Ong-Bak unless they follow the template set by 1970s Hong Kong martial arts films by casting an athletically gifted and charismatic martial artist and put him through one physical challenge after another that will leave audiences gasping in amazement.

Now, admittedly, Jaa isn’t the most charismatic actor in Ong-Bak, although his acting and screen presence improves a lot by Tom-Yung-Goong. But despite his awkwardness in acting, he is truly amazing to look at whenever he’s in motion. In the first scene, he and a bunch of other stuntmen/martial artists are competing to take a scarf that’s been tied around a branch somewhere up a gigantic tree. Even though he’s covered with dried mud like all the other men, the way he moves is just really distinct from everyone else: his poise, precision, and just sheer acrobatic grace. He scoots from one branch to another faster than my cat with a poop stuck in her butt.

Every time Jaa does something incredible, like leaping through a coil of barbed wire with his feet first, we get a repeat shot, usually from another angle, just so we can marvel at what he can do. I realize some people scoff at this but really, why not? That’s what we’re paying to see, right?

I’ll be honest: if I had Jaa’s skills, I would never walk into a room like a normal person. I’d be leaping in through windows or doing a double backwards somersault through the door all the damn time. ALL THE DAMN TIME. I’d eat my meals doing a one-armed handstand pushup and you don’t even want know how I’d use the toilet. But that’s why I’m not Tony Jaa.

In the end, the tough guy from the countryside narratives are wishful fantasies of justice for people who don’t normally get a chance to see it in real life, channeled through someone who not only represents the best of who they are, but who is proud of where he comes from. Just like delinquents and gangster stories, it’s about rejecting shame and stigma and instead glorying in who you are.

And also like those stories, tough guy stories also reassure people of the importance of group values and responsibilities to each other. The villagers give Ting all their money for his trip to Bangkok–money that Humlae later steals for gambling because he’s lost his country values–and in the end, in order to prepare against his final opponent, Saming (Chattapong Pantana-Angkul), Ting chews the traditional herb given to him by the village head monk and spits it over his muscles, in contrast to Saming, who injects himself with synthetic stimulants or whatever drugs they are.

Aside from justice, the other important element of the tough guy story is a redemption arc for someone, in this case Humlae, who realizes that he’s become kind of an asshole and decides to do good by his village by sacrificing his life. In the end, Ting returns to his village with Humlae’s ashes for the village celebration, and the last we see of him, he is ordained as a monk, untouched by the time he spent in Bangkok. He’s no last unicorn who doesn’t feel like he belongs back in his village. Not to mention, he has the humility to be a monk and not some kind of hero who needs to be rewarded with a babe or money.

So, by now, you’ve probably noticed the strain of anti-capitalism and the attachment to cultural values in all of the stories that I’ve written about. Who knew we were getting Marxist philosophy in pop culture through stories about dudes beating each other up?