Note: This is the second part of the series Tough Guys, Gangsters, and Delinquents in Asian Pop Culture. If you haven’t yet, you can read Part 1 here. I’m really excited because Crows is one of my favourite manga (if not my absolute favourite), and it’s inspired a lot of the fiction I write. Please be warned that this is full of spoilers, including what happens to the characters at the end. Also, scanlations are from Paula and Dangerers and you should be reading them from right to left like a civilized person.

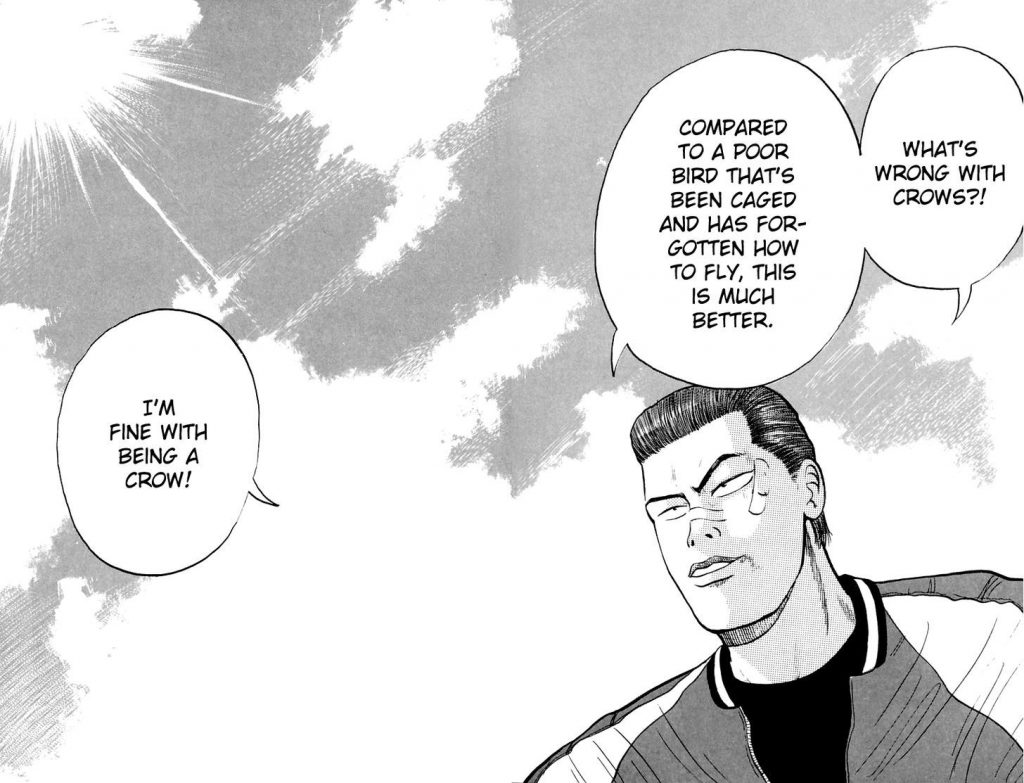

“There’s nothing wrong with being a crow. Compared to a poor bird that’s been caged and has forgotten how to fly, crows are much better. Being a crow is good enough for me.”

A long time ago, I worked for a non-profit in Hong Kong that provides arts courses to schools. One winter holiday, I was asked to handle a boys’ secondary school in Tin Shui Wai, at an area known for triad activity and just general hooliganism. The first thing the principal said to me when I showed up was “Better make sure you’re on the bus home by five PM.”

The school had decided to force all the worst, most delinquent students who’d skipped classes during the year to come to school for five days during the holiday or else they’d be kicked out. And not just that, they wanted the kids to learn a play, specifically A Christmas Carol, and in English, no less.

When I walked into the room and explained what we had to do, one of the boys threw a table at me and walked out. The five days were pretty much torture for both me and the boys, and there was no Stand and Deliver or Dangerous Minds moment. No one learned a single line from the play, and I mostly conversed with a couple of the nicer boys while the others slept or quarrelled. The only achievement I ever had was getting them to take their fights to the basketball court.

I was extremely relieved when the workshop was over, but I also felt bad for those boys. Some of them were assholes, but most of them just had too much of what you could call violent energy. In an older time, these kids would have been trained as warriors or hunters, but there’s no room for them in the world now, except as criminals.

If I may get my Marx and Foucault on, modern society relies on institutions like schools to make us productive consumers, but there will always be people who just don’t have the right docility of temperament, and we call them delinquents.

Delinquents and outlaws have always appeared in manga, like the 1980s bestsellers Kyou Kara Ore Wa!! (about a pair of boys who decide to dedicate themselves to the delinquent lifestyle) and Bad Boys (a seinen manga about a motorcycle gang). But there was a sudden popularity explosion in the 1990s of delinquent manga, which I’ve theorized in Part 1 has to do with the anti-establishment mood of the time.

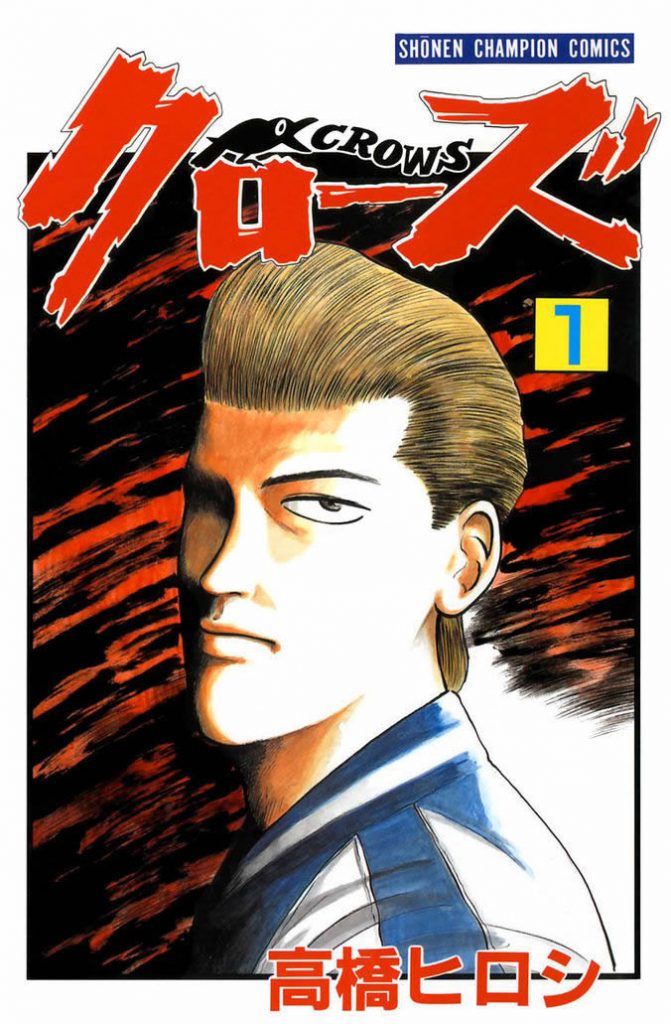

Crows came out in 1990 and is one of the most popular and highly influential delinquent manga. It’s produced a sequel, Worst, and three films, two of which were directed by Miike Takashi (who directed tender romance Audition, family comedy Ichi the Killer, and historical drama 13 Assassins). Let’s all just ignore the third Crows movie.

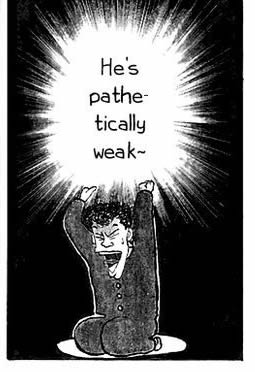

The manga follows the adventures of self-described “demon in a fight” Harumichi Bouya, who is almost immediately knocked out after hitting his head on a handrail after he appears. He’s quickly dismissed as a weakling, and even perennial bullying victim Yasu thinks he’s a dumbass.

Bouya is a transfer student to Suzuran All-Boys High School, which is also known as the “Crows School” because every student is a delinquent or a “crow”. If you’ve ever witnessed a bunch of crows pecking a pigeon to death, fucking up garbage cans, or making pets cry, you know exactly why delinquents are called crows. Crows (the birds) are more yakuza than yakuza.

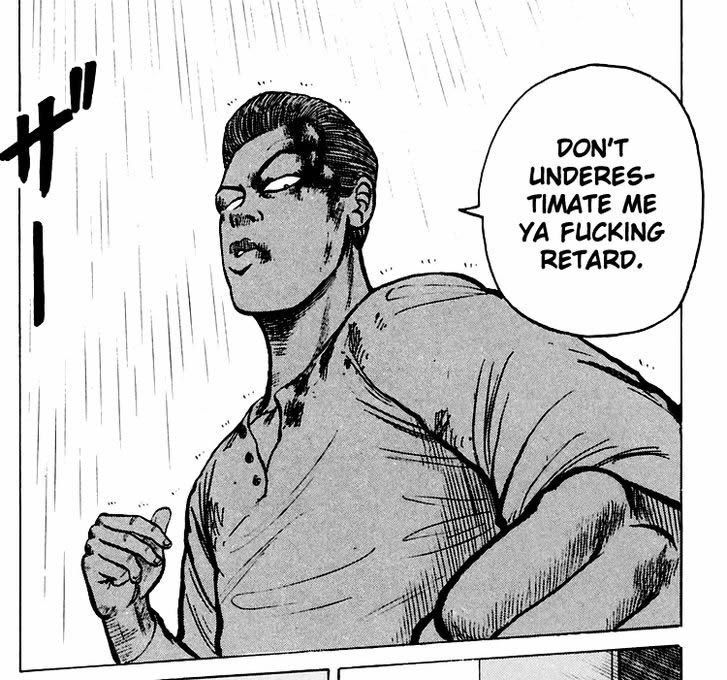

But while Bouya is definitely a dumbass prone to moments of extreme clumsiness, he is not a weakling. The widely feared Rindaman sums him up best: “He might be an idiot, but he’s an idiot that’s good in a fight.” Considering that Rindaman himself isn’t the brightest firework in the sky, and he’s considered the strongest fighter in the school (and possibly the region) who Bouya himself can’t defeat, that’s both the highest praise and the lowest insult.

While we also get to see the points of view of other characters, we mostly follow Bouya as he recovers from that initial fumble, sticks up for Yasu (only because he wants to meet Yasu’s pretty sister) and in short order, manages to kick the shit out of almost everyone not only at Suzuran, but also contenders from other schools, a motorcycle gang, and many others.

Most of the characters in Crows are boys from working class or lower middle class backgrounds, and it’s important to note that we’ve historically associated a kind of red-blooded (and often violent) masculinity with these classes. (I know women can be violent too, but since almost all the characters in Crows are boys and men, I’m going to speak on female violence in another post.)

During the 1980s, this type of masculinity was starting to become obsolete in industrialized countries because it had no useful role in a consumer society. Then the 1990s came, and Japan’s economic bubble burst, and the idea of going to school and getting good grades and joining a good company suddenly seemed hollow or unattainable. The political scandals that happened around the same time also proved that elites were corrupt and dishonourable. By this time, the idea of masculinity in the industrialized world had become unmoored and confused. In the West, books and films about men struggling to find places in the modern world like Fight Club and Trainspotting came out.

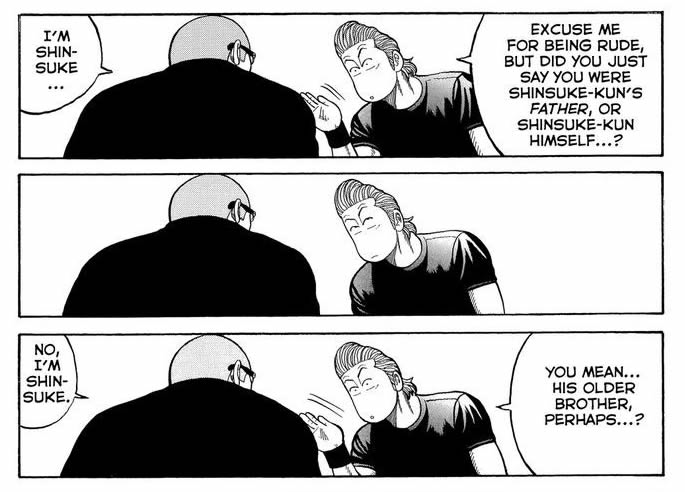

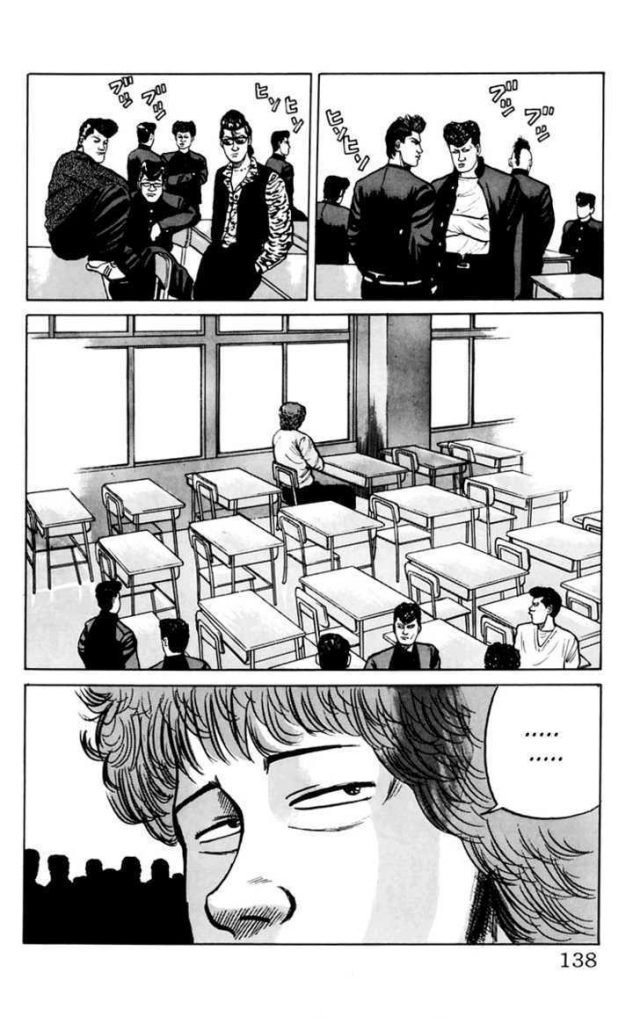

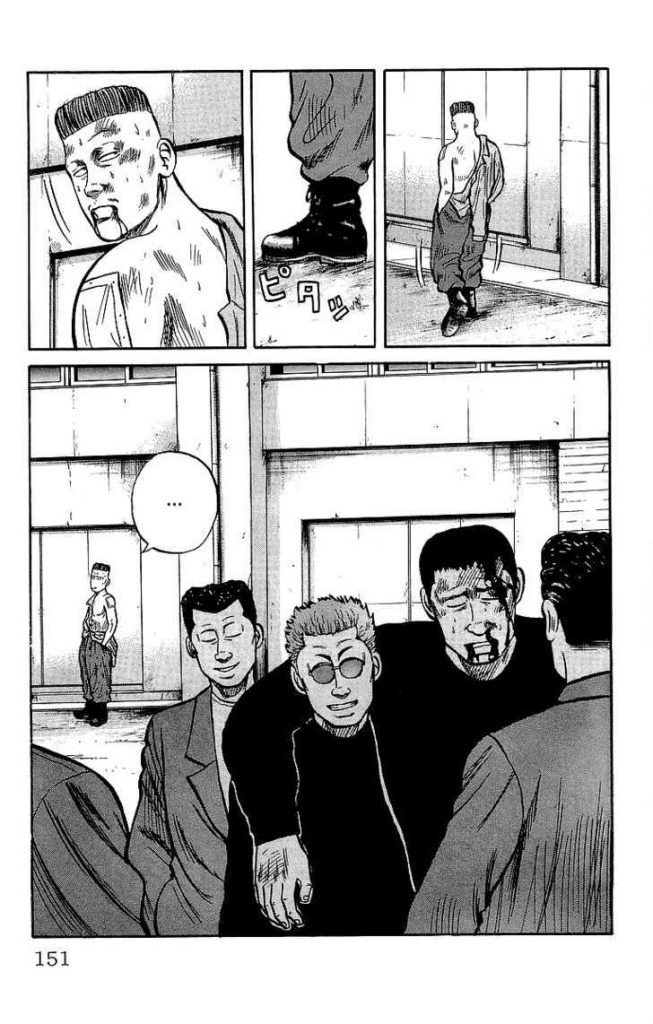

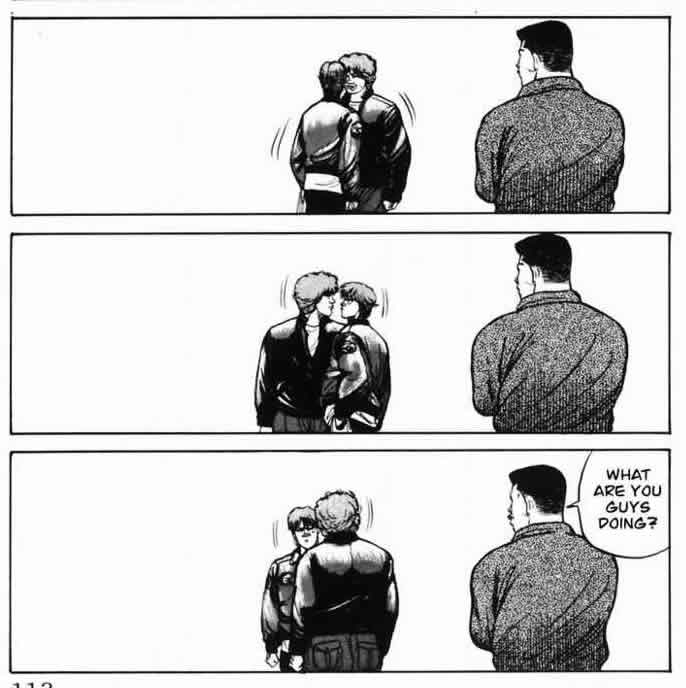

In East Asia, though, we had manga like Crows, where, unlike boys and men who’ve given into the system, delinquents haven’t lost their masculinity. I mean, even just looking at the artwork, the characters are all drawn to look very butch, to the point that these characters, who are mostly between fifteen to seventeen years old look like men in their twenties (also, the drawings do improve over time). I do think mangaka Takahashi Hiroshi is aware of this, though, hence this joke.

Fighting and conquest are basically the two things that are generally associated with this type of masculinity, and Takahashi, whose childhood was very similar to his characters’, sees it as something normal and part of being a working class boy. As Bouya says, “The kind of guys that gather at the place called Crows High–they hate studying and find sports too much of a hassle. Guys that don’t know what to do with themselves. They hate having nothing to do and just want some place to release all their built-up tension.”

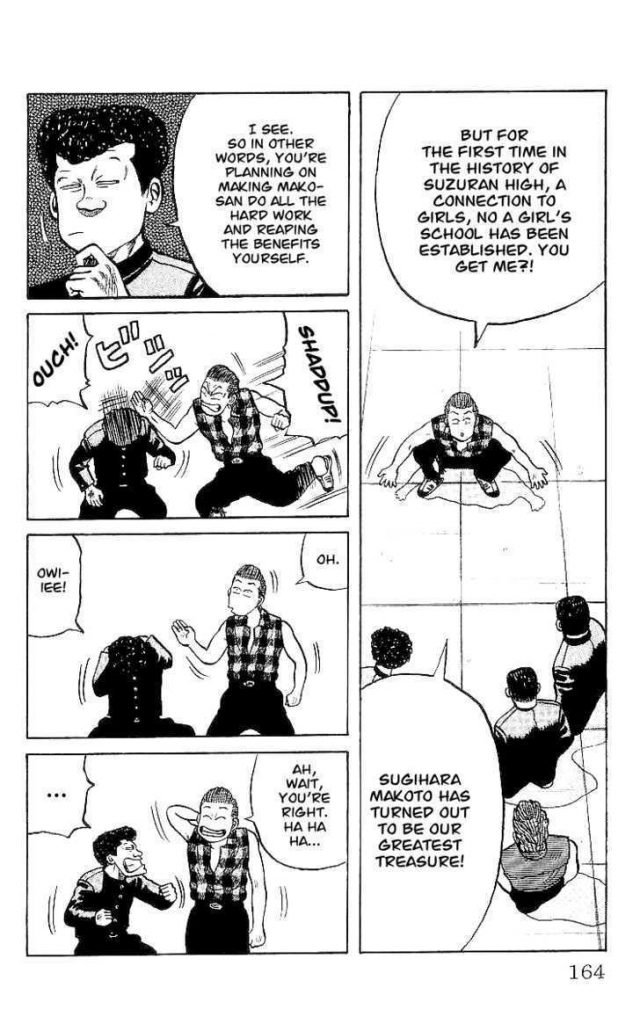

Ninety-nine percent of the conflict in Crows comes from the struggle to be the strongest, first in Suzuran, then the town that everyone lives in, and even beyond. (The other one percent comes from the delinquents’ dismal attempts at impressing girls–most of the boys are too scary-looking–and their jealous wrath whenever one of them manages to get a girlfriend.)

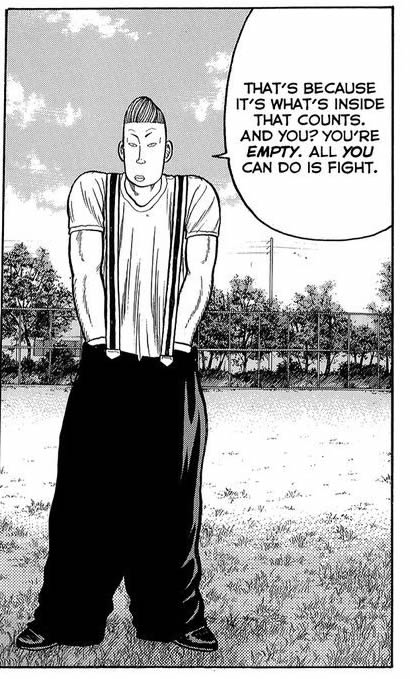

But although fighting is a big part of what it means to be a delinquent, in Crows, pummeling people isn’t what makes you a man; it’s why and how you fight that defines you.

Even though might often makes right in the world of Crows, brute strength in service of ambition or greed may get you far, but it’s worth very little if you can’t find friends who will be loyal to you and watch your back. Anyone who seeks power to compensate for loneliness or some kind of weakness may be a good fighter but he’s not necessarily a great one, much less a leader.

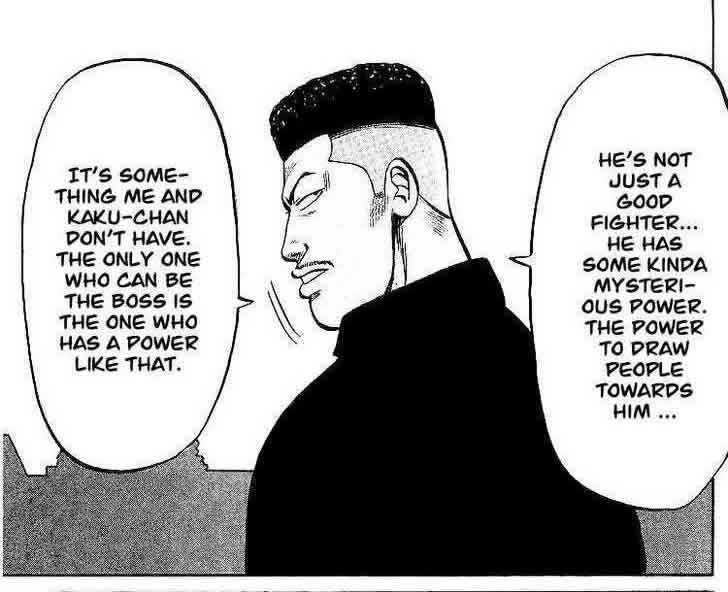

Greatness is seen as a matter of heart and charisma like how the character Bulldog is described: “It’s not like you followed the kid who use his strength or money and said, ‘Follow me.’ A boss is someone that people gravitate towards, and one day, he realizes himself that everyone had been calling him ‘Boss’.”

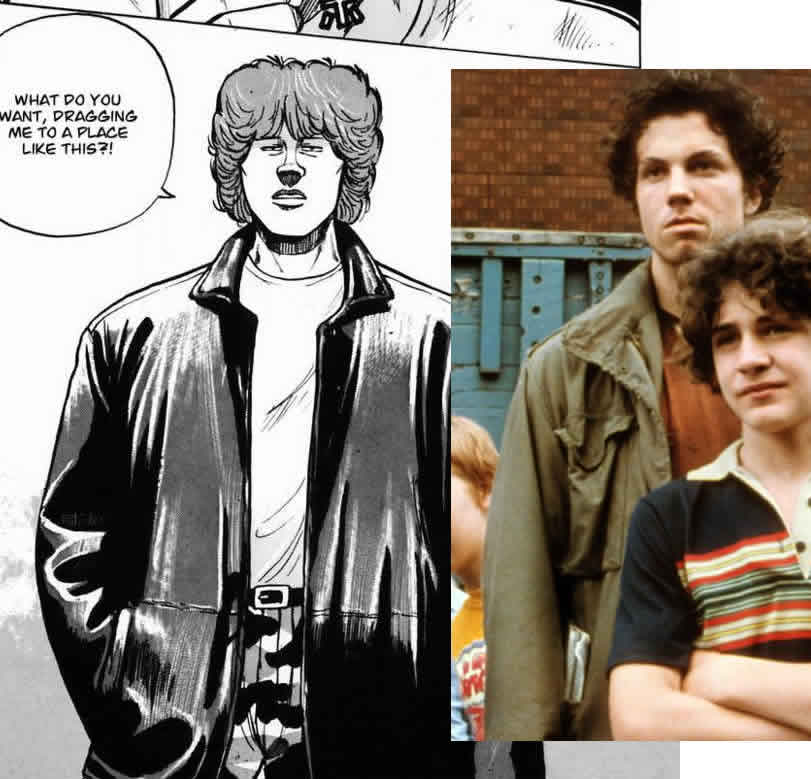

Takahashi is really interested in how amazing strength doesn’t necessarily make you a well-adjusted man. Take Rindaman, for example, a character based on Ricky in My Bodyguard, a kid with a tragic past who fights not because he wants to but because his size and strength make him a target. But Rindaman’s strength is also what makes him a lonely figure.

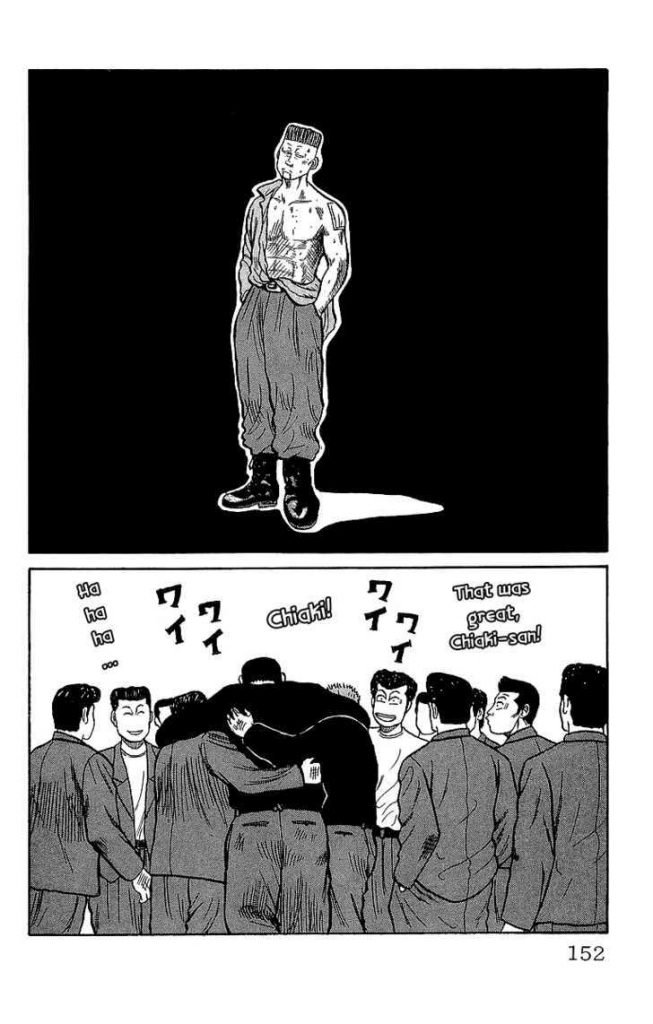

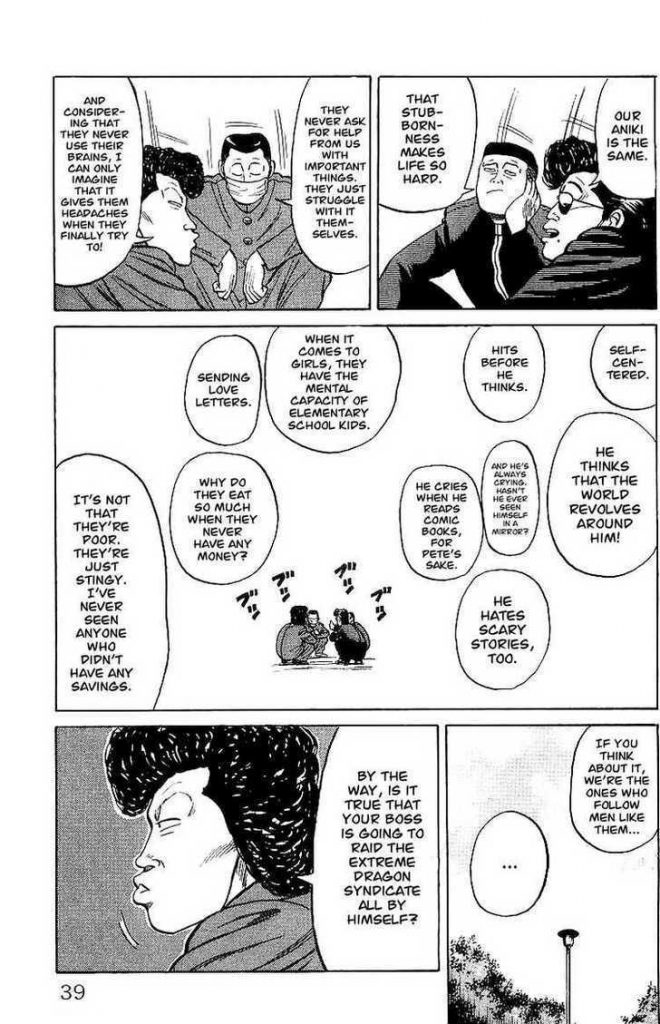

In fact, something that comes up over and over again in Crows whenever extremely strong fighters show up is how alienated they are, and how messed up they are because they don’t have friends. It’s a pretty sophisticated and empathetic look at the essence of being a man. Although this kind of camaraderie exists in all social classes, there’s a particular appeal in delinquent friendships because of the dangers that they face. You can win all the fights but it doesn’t matter how strong you are if you’re alone at the end of it.

Having a well-adjusted sense of masculinity means that you have the kind of friendships that the delinquents have with each other in Crows. It’s not based on money or status or even strength, but loyalty and maybe just hanging out and being stupid together.

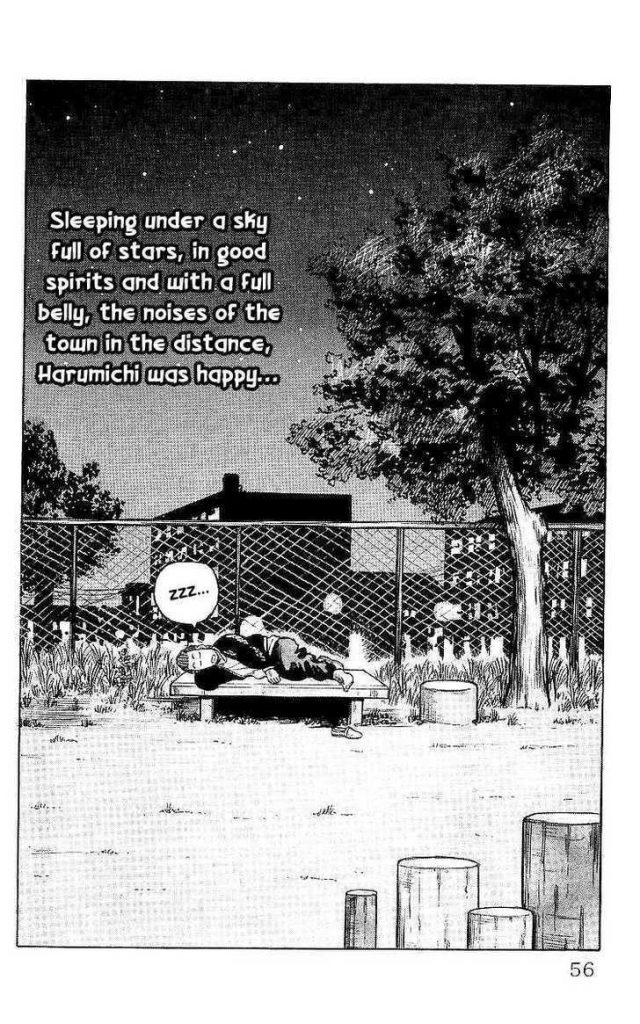

Bouya is the probably the best example of someone with a well-adjusted masculinity. He doesn’t have any burden or darkness, and while it’s entirely possible it’s because he’s too dumb, it’s also because he just likes people. He enjoys fighting because he’s good at it, the idea of being a leader horrifies and pisses him off, and he doesn’t really hold anything against people he’s fought. In fact, he even ends up making friends with most of them or at least draws them out of their lonely shells to…be as immature as he is. And in a lot of ways, that’s what Bouya’s true strength is: the ability to make enemies into friends (and lower their IQs to his level).

Also, I think it’s really significant that the only practically unbeatable character in Crows is the best example of anti-materialistic and anti-establishment qualities. In a way, Bouya is kind of a buddha.

Crows has been a big influence on later generations of delinquent manga, but I think the fact that Takahashi was writing out of experience really makes a difference in his treatment of his characters. He has a lot of sympathy for them, even the assholes, and especially for the weak and damaged ones. He doesn’t just focus on the strong fighters, but also gives room to their underlings and how they deal with their own troubles with their bosses.

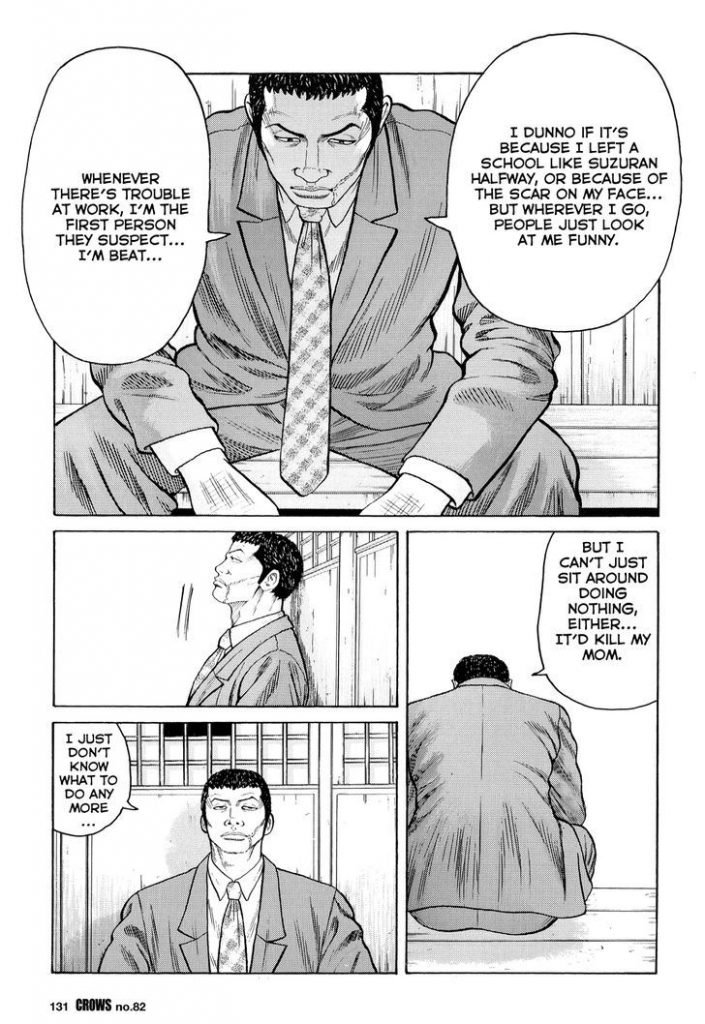

Also, I think Takahashi’s background is the reason why Crows turns a bit more somber as the protagonists grow up and begin to contemplate their future (or lack of) outside Suzuran High. Takahashi understands that for most of these kids, growing up means either compromising in mainstream society or becoming a true criminal and joining the yakuza. Some characters won’t let go of the belief that “It’s better to be hated by society as a crow than live life as a caged bird” but these characters either die or just disappear.

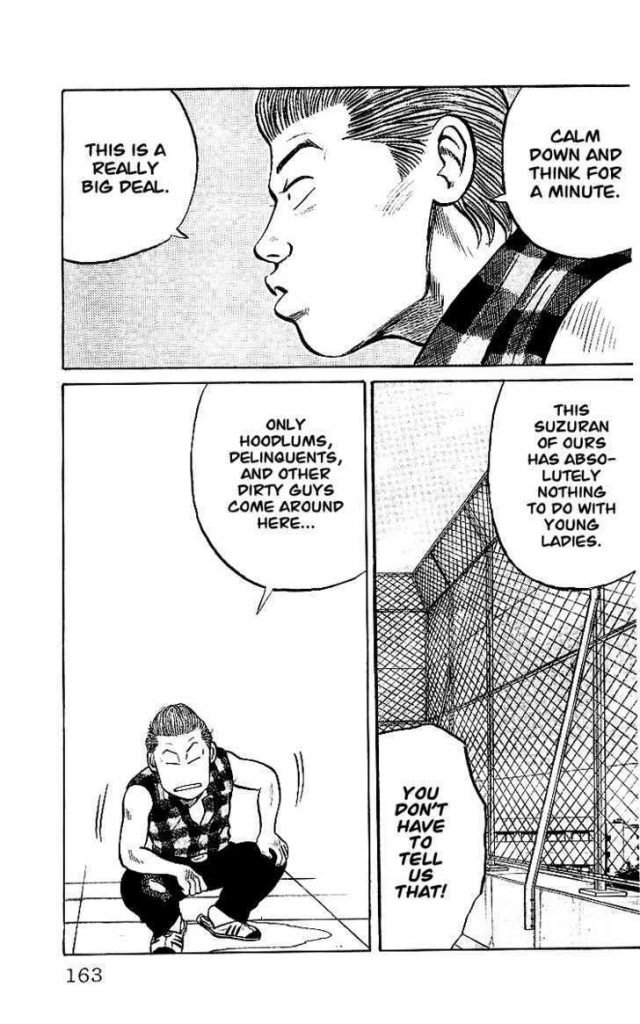

However, he also doesn’t shy away from showing how compromising too much in mainstream society can eat your self worth up and take your masculinity away from you, like Senda here.

Most of the protagonists end up with happy-enough endings although I can see why some readers would be disappointed that they’ve just basically become regular adults. The system always wins out in the end, although Takahashi lets most of the characters keep their healthy masculinity by not forcing them into soul-sucking jobs.

Bouya is the only one who doesn’t have to grow up and choose to become either an adult in mainstream society or a yakuza; he gets held back another year in school. It’s a little unrealistic, considering that most of the other delinquents don’t seem to show up for school at all and still manage to graduate, but I guess Takahashi really didn’t have a choice. In an older society, Bouya would’ve been a ronin, maybe even someone like Miyamoto Musashi (although Bouya can barely read a book, much less write one), happily wandering the country looking for people to hang out with and testing his strength.

But there is no room left for ronin in this world. It’s a little sad to think that one of the most positive masculine characters in the manga is the one that has no real options in modern society.

In the Crows Zero movies directed by Miike, the whole question of what happens to these kids when they grow up is kind of sidestepped by setting the film before Bouya’s arrival at Suzuran and focussing the plot on a yakuza heir, Takiya Genji, whose aim is to beat Rindaman and conquer Suzuran. The films are great on their own, and the simple storyline really benefits from the way Miike infuses his work with kinetic energy and weird humour.

Incidentally, I once read a review of the films by a writer not familiar with Asian culture who obviously felt really uncomfortable about the close friendships of the characters. I found the review quite homophobic and culturally ignorant. It’s perfectly common for boys in Asia to have close friendships that include being emotionally vulnerable around each other and being physically comfortable around each other. And yes, that includes being friends with gay boys and men. It’s too bad that homophobia has wrecked male friendship so much in the West that boys and men can’t enjoy this kind of intimacy, which is so much a part of a healthy masculinity.

But back to Crows, Takahashi once wrote, “I want to draw comics that aren’t good for everyone, but rather makes some people say, ‘This is a book I like.’”

What can I say? This is a book I like.