Note: Welcome to the first of my series Tough Guys, Gangsters, and Delinquents in Asian Pop Culture, where I get to write about…well…tough guys, gangsters, and delinquents! I started this series because I couldn’t find English-language essays and articles online about Asian pop culture that analyzed things from an Asian perspective and had a sense of humour about the entire thing. So for my inaugural post, here is the classic Hong Kong gangster film, Young and Dangerous! More spoilers than hair products ahead!

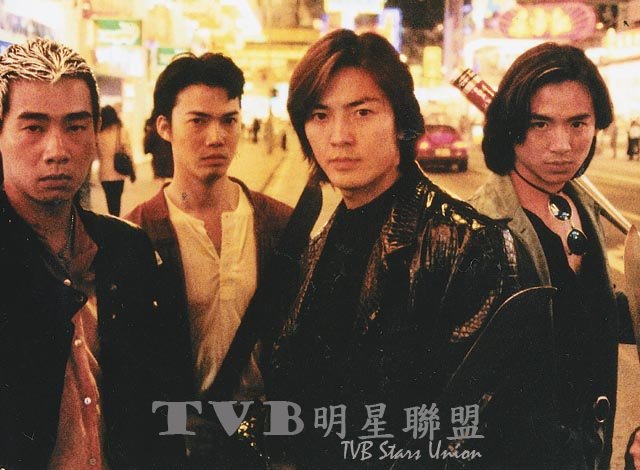

Young and Dangerous is the movie that launched a hundred thousand (and probably even more) hairdos across Asia when it came out in 1996. Previous to this, during the early nineties, most teenaged boys–and not a few girls–had hairstyles modelled after one of the Heavenly Kings of Hong Kong pop: Andy Lau if you fancied yourself as a man about town, Aaron Kwok if you saw yourself as a pretty boy, Leon Lai if you wanted to get beaten up at school, and Jacky Cheung if you preferred not to attract too much attention to your appearance.

I probably don’t even need to say which is which.

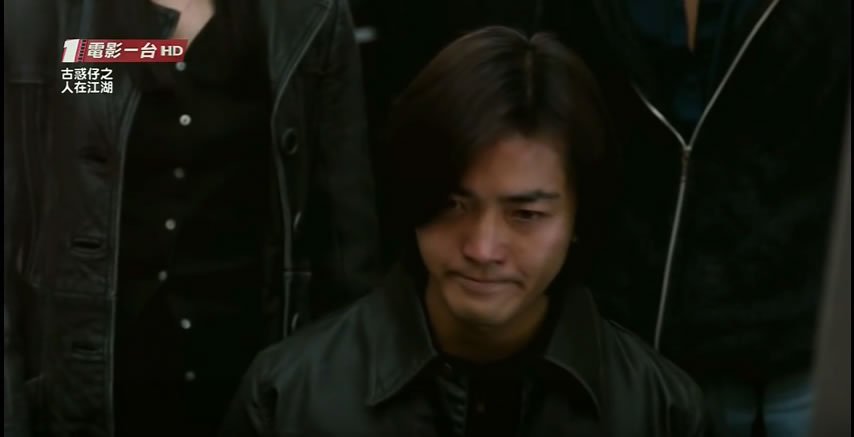

But then Ekin Cheng showed up as Chan Ho-nam in Young and Dangerous with his layered, wavy haircut and within a few weeks (you had to let your hair grow out first), every dude who wanted to be a badass suddenly sported this haircut, not just in Hong Kong but almost anywhere there was a Chinese community with at least two annoying teenagers or an uncle facing a mid-life crisis.

Young and Dangerous isn’t really a standard triad movie; it glosses over all the depressing shit that the real triads are involved in, like prostitution, gambling, extortion, murder, and drugs. (Incidentally, the reason the triads have such a huge control over the drug trade is thanks to the United States, who, in their zeal to destabilize China, supported the Kuomintang’s violent annexation of a region in Myanmar for the cultivation of opium and thus paving the way for the 14K triad society and the rise of the Golden Triangle. Because that’s what democracy apparently is about–destroying the lives of innocent people to bring freedom to…well, I’m not really sure to whom. But who cares? Communist China is the real enemy or whatever.) Back to triad movies: do you think this jumping in joy scene would ever happen in a real gangster movie after the main characters shake someone down? I mean, Ho-nam (in the short sleeves) looks like he’s trying to act like Kamen Rider, for God’s sake.

This isn’t to say that the movie doesn’t deal with any of the triad’s business: the first time we see adult Ho-nam, he’s getting ready to assassinate a rival gangster with a hairdryer in a massage parlour bathhouse. This is a good reminder not to trust anyone using a hairdryer on their dry hair, by the way. I also want to point out here that his sworn brother Chicken (Jordan Chan) is late to the murdering, foreshadowing another important fight that he’ll be missing later in the movie, which leaves him and Ho-nam in disgrace.

There are quite a few scenes of violence, but they have that slightly unreal 1980s quality, and the blurry camera work implying frenzied action just makes them feel even more cartoonish. It’s like the violence is there because it has to be, but it’s not the point of the film. Instead of focussing on the grittiness of the triad world, Young and Dangerous uses it as an extension of the things that mattered to many boys and young men: revenge on bullies, defying authority figures, chasing after (or being chased by) girls, getting into fights and adventures, and most important of all, a sense of belonging and loyalty to a group. Even the comic relief priest (Spencer Lam) compares being a Christian to joining a gang, noting that “Jesus never got caught by the cops, he was killed but came back to life three days later!”

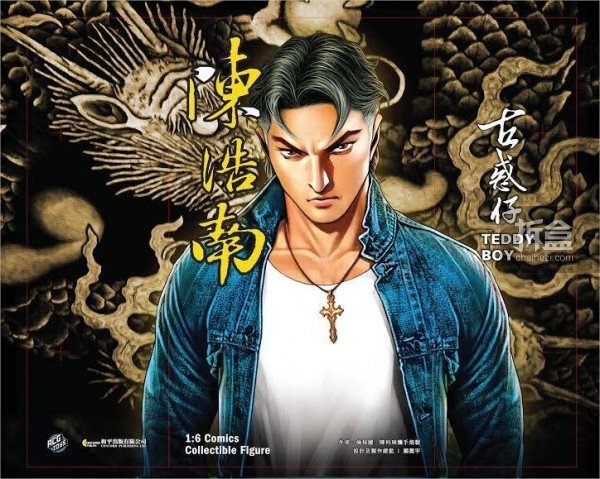

A lot of these themes come from the Hong Kong manhua (comic book) Teddyboy by Cowman (牛佬) that the movie is based on. Stories about outcasts and hoodlums have always been popular with young people–by the way, I feel like I’m growing a white beard every time I write “young people”–which makes sense: it’s a time of life when you’re feeling alienated and misunderstood, and it’s easy to identify with outcasts.

But it’s important to highlight how relevant to its success that Young and Dangerous came out in 1996. In the 1990s, industrialized nations entered the stage in the historical cycle where the norms of society are questioned and challenged. It happened in the 1920s, in the 1960s, and it’s happening again right now. In the US, this phase was fronted by grunge music and fashion and in East Asia, comic books led the way in revealing that young people weren’t happy about the prospect of being forced to conform and were disillusioned about the merits of being a productive member of society.

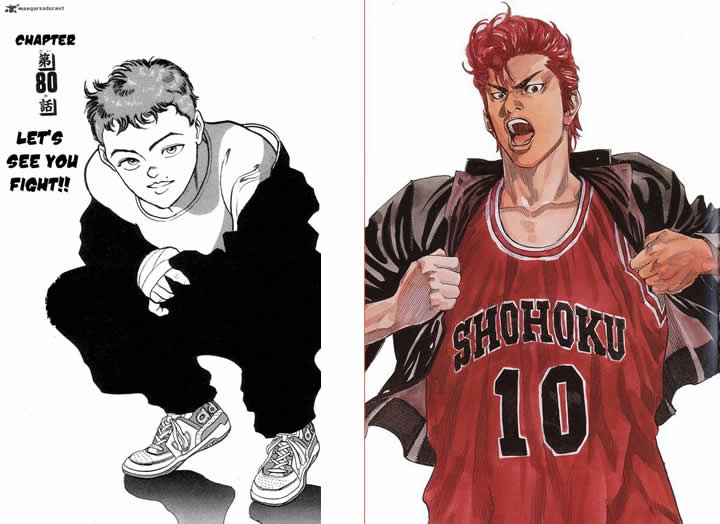

Mangas and manhuas rely a lot on instantaneous feedback–they get canceled right away when their sales and ranking drop–which means that whatever is being published is a pretty good indicator of what people want to see. In the 1980s, the most popular manga were sports manga like Touch, adventure fantasy like Dragonball, or post-apocalyptic (a big theme in the 1980s) like Fist of the North Star. But by the time the mid-1990s rolled around, you’ll see clear similarities in the popular shounen manga of the time: Slam Dunk, about a delinquent boy who joins a basketball team; Baki the Grappler, about a wrestler who rejects traditional training to go learn unorthodox ways; Crows, about a bunch of delinquents fighting their way through the worst high school in Japan; and Initial D, about a bunch of teenaged boys involved in illegal street racing

But these stories aren’t nihilistic and anti-social; they’re about finding a tribe of other misfits, and they also chart the growth and maturity of male characters from boys to men. If you’re estranged from your father or don’t get to see him regularly enough to talk about these things, these stories may be the only way you can learn about what it means to be a decent man.

In Hong Kong, the big delinquent manhua was Teddyboy, which came out in 1992. Suddenly, there was a character who was instantly recognizable to Hong Kong readers, especially working class ones who grew up in housing estates where there was a huge triad presence. Readers could see themselves and people they knew in Chan Ho-nam and his friends, and there was something vindicating about following Ho-nam’s rise in the triad underworld, going from a 49er (the lowest-ranking member in a triad society) to a Red Pole (enforcer) to Dragon Head (leader) of a fictional triad organization, the Hung Hing Society.

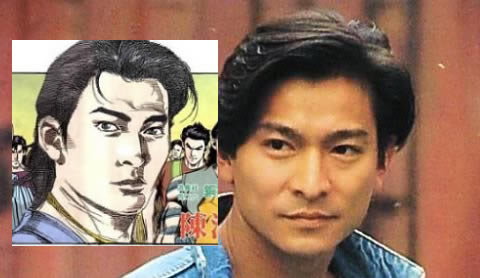

Originally, Cowman used Heavenly King Andy Lau’s face as a model for Ho-nam’s character (you can see the resemblance in the picture below and a comparison between an Andy-looking Ho-nam and an Ekin-looking one). However, I’m not going to speculate too much on what a Ho-nam played by Andy would have been like, since Andy was too old by the time Young and Dangerous was made, anyway.

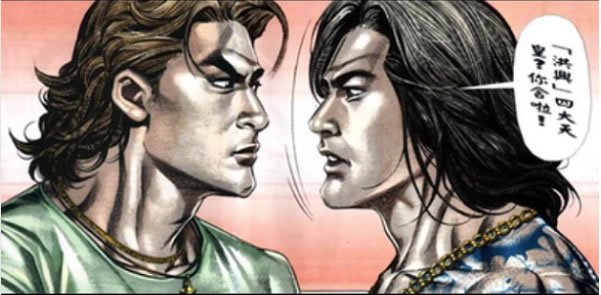

Comic book scans thanks to Teddyboy Support

Comic book scans thanks to Teddyboy Support

Instead, the role went to Ekin Cheng, who became a huge star after this movie. I’m going to come clean here first and admit that I have never been very much impressed by Ekin. I can’t even judge his level of pulchritude objectively because I think he looks like My Melody.

However, I do think he was the perfect Ho-nam because this is a role that relies more on charisma and charm than talent, and Ekin’s woodenness actually works in his favour by making him look cool and unflappable. Whether he’s carrying out a hit on a rival gangster or being stabbed in a gang fight, Ekin’s Ho-nam looks only mildly annoyed, because shit’s not a big deal, okay, man?

When Ho-nam is forced to go through a gauntlet of beatings on his knees in order to light funeral incense for his deceased boss, a better (or worse?) actor might use this as a chance to show off his dramatic acting skills, but Ekin simply musters up a resigned sigh, like he just found out that his mom added a little too much ginger to his congee.

Okay, I’ll stop ragging on Ekin because, as I said, I really do think he’s responsible for a lot of Young and Dangerous’ success. Ekin may not be an actor, but he’s undeniably a movie star, and without that charisma, Young and Dangerous wouldn’t have had the same immense cultural impact that it did. Ekin’s prettiness and general sweetness (he doesn’t look like he’d ever turn away a lost puppy) makes the violence in the movie feel like high-spirited fun. His Ho-nam isn’t a violent thug, he’s the coolest guy at school multiplied by a million, the guy whose friends would die for him (or at least catch a beating), the guy that girls swoon over instead of fear. And the girls do swoon, like Smartie (Gigi Lai) who gets busted by Ho-nam and his crew for stealing his car, is later rescued by him from being forced to act in a porno, and ends up falling in love.

Most of the time, there are only really three roles available for chicks in triad movies: hooker, girlfriend, family member. (A big exception is Portland Street Blues, a Young and Dangerous spinoff featuring a female triad member that I’ll write about later.) I get that the point of this movie is to focus on Ho-nam, so I’m not too bothered because I think what’s more important is to see whether chicks are given humanity within the roles they have.

With Smartie, we have someone who’s more than a bland hot chick who only exists to underscore how great Ho-nam is. She’s a triad member herself, and is brash, cocky, and independent. She has a disability of sorts (she stutters) that doesn’t stop her from doing or saying what she wants, she’s happily sexual with Ho-nam without any apology or shame, and she can’t even cook (one of Ho-nam’s buddies has to take over in the kitchen when Smartie tries to make soup). Smartie is basically just like Ho-nam and his friends, and I think that anyone who has hung out with working class Hong Kong chicks would know someone like her.

Even Chicken’s girlfriend (Suki Chan), who ends up being drugged and raped by an equally drugged-up Ho-nam, isn’t just a victim: she stands up for herself and demands that Ho-nam take responsibility (he eventually does and accepts being kicked out of Hung Hing, which is how we know that he’s solid).

The movie is reasonably sympathetic towards the plight of chicks in the triad underworld. We see women being sexually harassed by the nasty Ba Bai (Joe Chen), Ugly Kwan (Francis Ng) treats his girlfriend like a possession, Chicken sleeps around with various chicks and cheats on his girlfriend. And these men are all punished: Ba Bai and Ugly Kwan are killed, while Chicken is exiled to Taiwan (although he gets to come back later and have a hero moment).

The idea that the way you conduct yourself around women determines your character has roots in wuxia, which is the ancestor of stories about outsiders. Wuxia stories have been around for hundreds of years, going all the way back to the grand wuxia classic Water Margin (about a huge group of outlaws in the Song Dynasty), and they usually centre on characters who have chosen to live in the jianghu, the world that operates outside of the mainstream one. It’s pretty interesting that people’s tastes have been consistent throughout the centuries, isn’t it?

Young and Dangerous ended up spawning sequels, a prequel, a remake, and several spinoffs, some of which were pretty good, but none really had the same kind of impact that the original movie had. I’m sure that the people involved in making the film had no idea it would become so iconic, and I’m curious about director Andrew Lau’s (yes, the same dude who did Infernal Affairs, which got him a lot of praise, and Initial D, which didn’t) intentions, as well. 1996 was the year before handover, and Lau has been pretty frank about his dislike of British imperialism (dude is so badass, I forgive him for what he did to Initial D). It just seems like too much of a coincidence to me that Lau would put out this movie about the triad at this time, considering that the triads’ roots are based in secret societies dedicated to the overthrow of foreign rule, which is why one of the first laws enacted by the imperialist government was Ordinance No. 12 in 1845 for the suppression of triad societies.

Also, it’s pretty a pretty bold move to glamourize the triad, considering that the British put into place several ordinances to censor any speech “to encourage or to incite to crime, civil disorder or civil disobedience.” Kingsley Bolton and Christopher Hutton also point out in their academic article “Bad and Banned Language: Triad Secret Societies, the Censorship of the Cantonese Vernacular, and Colonial Language Policy in Hong Kong” that the imperialist government was very pro-censorship and anti-freedom of expression because “[Hong Kong’s colonial laws] tend to equate freedom with mischief.” Ironically, it wasn’t until the Basic Law came into effect after handover did Hong Kong enjoy legal freedom of expression (check out Article 16 of the Bill of Rights).

I can only conclude that Lau has pretty huge balls for making Young and Dangerous, although I don’t disagree that it’s basically a recruitment film for the triad. At one point in the film, after one of Ho-nam’s friends is killed in an ambush, Ho-nam tells his sobbing brother that this is just part of triad life: you either end up in hell or in jail. Seriously, that’s some dulce et decorum est language that makes me want to join the triad, and I’m not even a teenaged boy, and I hate running.

And if that doesn’t convince you how awesome triad life is, there’s the last scene where Ekin does the winner’s strut around Causeway Bay.

Look at him, he looks like that dude in school who no one was sure would graduate but somehow pulled it off and everyone’s really happy for him. When the reinstated Dragon Head Uncle Chiang (Simon Yam) shakes his hand, it looks like the principal is congratulating him on making it through. And the only expression Ekin can pull off is an abashed smile, like he knows he only pulled through because his mom threatened to get the principal fired. Oh, Ekin, thank God you have that pretty face.

In the next instalment of this series Tough Guys, Gangsters, and Delinquents in Asian Pop Culture, I’ll be looking at Japanese manga Crows (and touch on the films a little bit, too) and figuring out what it means to be a great fighter and what that has to do with being a good man and a great friend.

If you liked this post, you might like my fiction too (see the box below)!