Note: Yes, I keep writing about Johnnie To’s films, but I can’t help how much I love them. For this installment of the Tough Guys, Gangsters, and Delinquents in Asian Pop Culture series, Exiled has more spoilers than it has bullet holes, and that’s saying a lot!

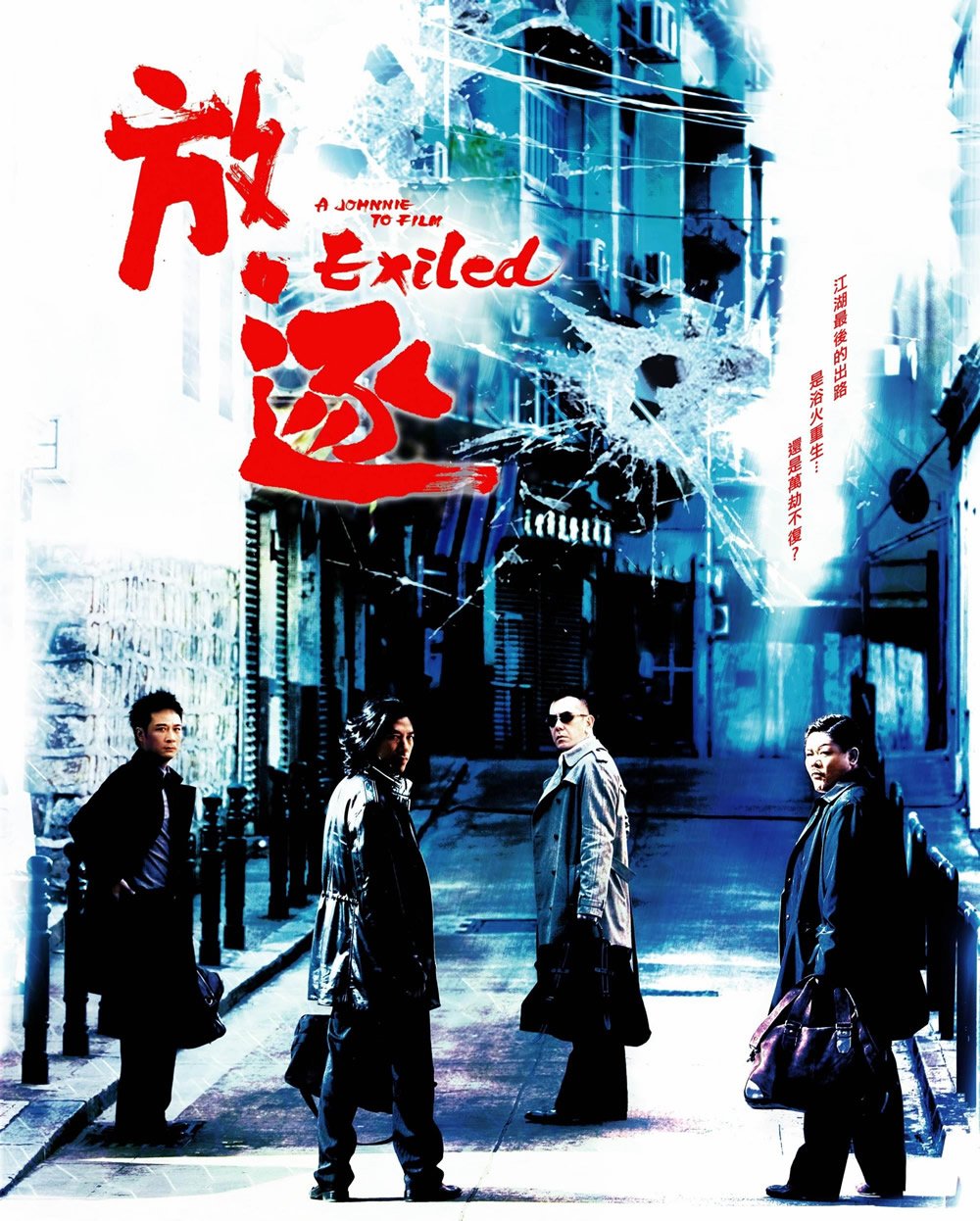

Exiled is the ultimate Johnnie To film with the coolest, most badass motherfucking gangsters doing gangster shit in the coolest, most badass motherfucking way. I watched it with my friend Gary, and when we stumbled out of the cinema, we immediately went to buy cigarettes, even though neither of us smoked. For at least a week afterwards, I annoyed all my friends by puffing on cigarettes like I was Richie Ren’s character Sergeant Chen (we’ll get to that later), one of my all-time favourite To characters.

This is not to say that Exiled is the best Johnnie To film. It rehashes many (if not all) of the same tropes and themes from his previous films, and both character development and narrative seem to rest a lot on the charisma and personalities of the usual crew of To actors. A (male) friend of mine who isn’t a To fan said, after watching it on my recommendation, “Where is the character development in this movie? And why are the only women in this film a mother and a prostitute?”

Yes to all that, and there are inarguably many superior To films, but Exiled is pretty much a fan service movie for people who have loved To films since The Mission. Although it shares a similar “glorious death” ending as 13 Assassins, Exiled is about the bonds of friendship between men that trumps everything, even death and women. Brotherhood is practically fetishized in this movie–and again, I have to note how male relationships are often portrayed this way while female friendships often aren’t. If you think about it, in action movies, female action heroes are often friendless while male actions heroes often have at least one buddy.

Anyway, unlike 13 Assassins, which begins with a suicide, Exiled is a film about the inescapability of death that begins with a celebration of life. The first thing we hear is the jingling of bells that are attached to a baby anklet that Wo (Nick Cheung) puts on his month-old son. The anklets are good luck charms in Chinese tradition, usually with meant as a blessing for a child to be anchored in this world.

The sound of the jingling anklet also appears in different spots in the film, and usually just before something terrible happens to our gangster protagonists like an adorable portent of doom. There are a lot of things we can infer from that, but I’m choosing to think of it as meaning that these killers must die in order to preserve innocence and life.

The jingling underscores the fact that the catalyst for all of this violence and death is the birth of Wo’s son, which makes Wo decide to return to Macau with his family. Wo and his childhood buddies Tai (Francis Ng), Cat (Roy Cheung), Fat (Lam Seut), and Blaze (Anthony Wong) once used to work together in the triad until Tai and Wo try and fail to assassinate a triad head, Boss Fay (Simon Yam). Wo takes the fall and has to leave town (thus saving Tai’s ass), but that means he’s earned the enmity of Boss Fay.

Blaze and Fat, who are still working for Boss Fay, show up at Wo’s house to kill Wo on Boss Fay’s orders, while Tai and Cat are there to protect him. Yes, the question why Wo has chosen to come back in the first place is asked, and Wo simply replies that he was sick of running and wanted to go home with his family. Yes, it’s a dumb and selfish reason but mostly, his answer is the clearest sign to us that Wo is doomed.

Blaze, Tai, and Wo end up having a shootout in his house that has all the elements To admirers love in his films: the combination of choreography and mood, with the steam escaping from the soup pot ready to boil over as a metaphor and way of increasing tension, how Blaze and Tai approach killing differently, with Blaze’s coolness and Tai’s impatience.

The gunfight ends in a draw, and Blaze grudgingly agrees to help Wo pull off one last job so that Wo’s family will be provided for financially. This is followed by the most fan service sequence where we see the sworn brothers fixing up Wo’s flat and cooking and eating dinner together (needless to say, Francis Ng looks like he cooks a great meal).

While the point of this sequence is to demonstrate the bond between the sworn brothers that developed when they were children growing up together, a lot of the humour and charm rest in seeing these hard-bitten killers doing domestic things. Again, I wonder why–if these men are so cool because of their masculinity (and its presumed cold-bloodedness and distance from domesticity)–situations like this make the characters more appealing instead of less? Is it the contrast? I suppose it’s the same impulse that causes people to keep wild animals like tigers and bears as pets–the idea that something so wild and dangerous can be put under our control. For those of us in mainstream society, there’s a sense of power in seeing these men, who are intimidating outsiders, bend to our rules. I guess Michel Foucault was right.

This desire lies at the heart of the film: we want these prodigal sons to return to normal lives (and so do they, in fact) but they’re really only good at one thing and that is violence, and there is no way to reconcile the two, so they must die.

As portended by the baby anklet of doom, Wo is the first one to perish after failing to carry out the assassination that is supposed to get his family money. His widow, Jin (Josie Ho), tries and fails to take her revenge on his sworn brothers, chasing them out of her house with a gun when they try to take her away as a protective measure against Boss Fay. I’d like to stop here for a moment to note that while these men are killers, they do their best to protect the weak and innocent (like the Jin and the baby) whereas Jin, who is a mother, tries to kill her baby (and fortunately fails) and goes off to seek destruction via revenge by going around Macau asking shady people if they’ve seen the four killers. Later, she also shoots a defenceless (though bulletproof-vested) Blaze point blank because she is only capable of hurting people who are vulnerable. And she still fails at it because women are life-givers while men are dealers of death.

This kind of reminds me of that trope of the cheated-on wife going after the mistress instead of her husband; instead of blaming Wo, whose idiocy brought this on them, Jin blames Blaze instead, who really is just carrying out the threat that Wo was already aware of. I know that all of this irrational behaviour is to simply move the plot along but come on, though.

The nameless prostitute (Ellen Chan) is also a witness to male foolishness, but unlike helpless, innocent Jin, Nameless Prostitute manages to take advantage, scooping up cash and gold from the men around her. If the men are in the business of death, and Jin is in the business of life, Nameless Prostitute is in the business of money. Along with Sergeant Chen, she is arguably the only person who makes it out best, along with Sergeant Chen (who presumably takes Jin to safety along with a huge amount of gold). It’s interesting that they’re the also ones who are most closely associated with money (Sergeant Chen is one of the police officers guarding a convoy bearing an actual ton of gold bars). Is this another Marxist critique that no honourable death comes from attachment to money? Or is this the first film in this series without an underlying Marxist critique? I don’t even know.

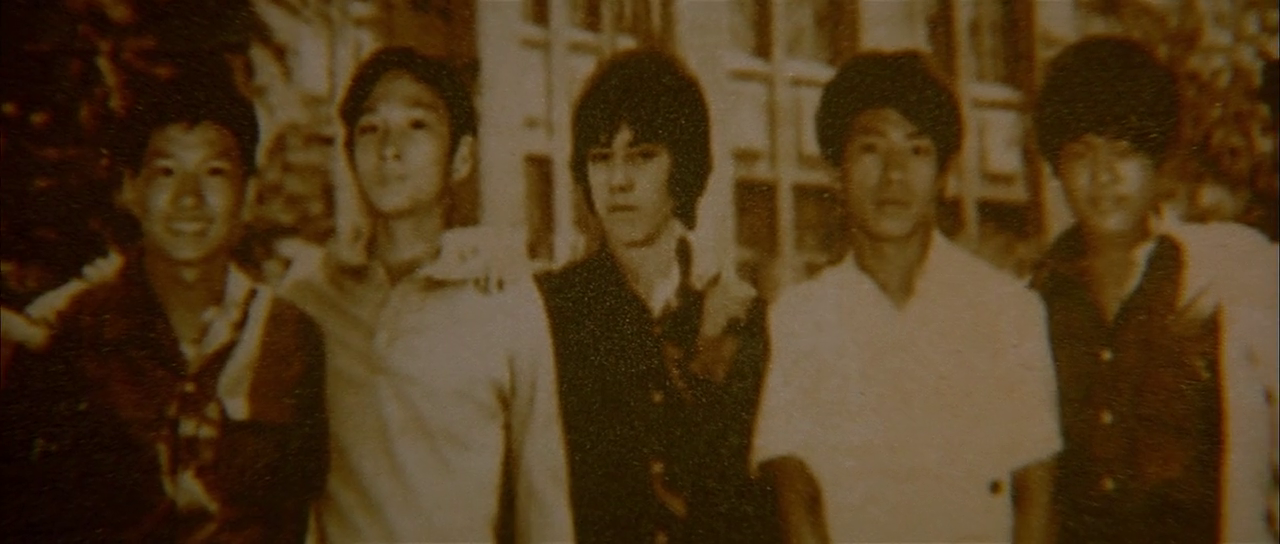

Because she’s a dumbass, Jin and the baby end up in Boss Fay’s clutches, and it’s his threat to kill them that has the four killers returning to Boss Fay to meet their doom (again augured by the baby anklet). To underscore his lack of honour in his willingness to use innocents, Boss Fay has previously been shot in the crotch, blatantly symbolizing his emasculation–no real man would hurt a woman and a baby, and no real man would ignore the bonds of brotherhood. Boss Fay is willing to let everyone leave except for Blaze, but of course, the code of honour and brotherhood means that no one does. The movie ends with all of the killers (and really, everyone else involved) dying with smiles on their faces and a close up of a group picture of them taken while they were just children. Might I note that all the actors look exactly like I thought they would have as kids?

I almost wasn’t going to include Exiled in this series because the movie doesn’t really contribute anything new to the genre; it’s basically a Western with the usual To elements dialed up to Spinal Tap level. It’s even set in Macau, which was a kind of Wild West for the triads before it returned to China. But for To admirers who are familiar with the genre and the character types, it’s easy for us to gloss over the film’s flaws to focus on just the sheer stylishness and coolness of it, especially when it comes to the gunfights.

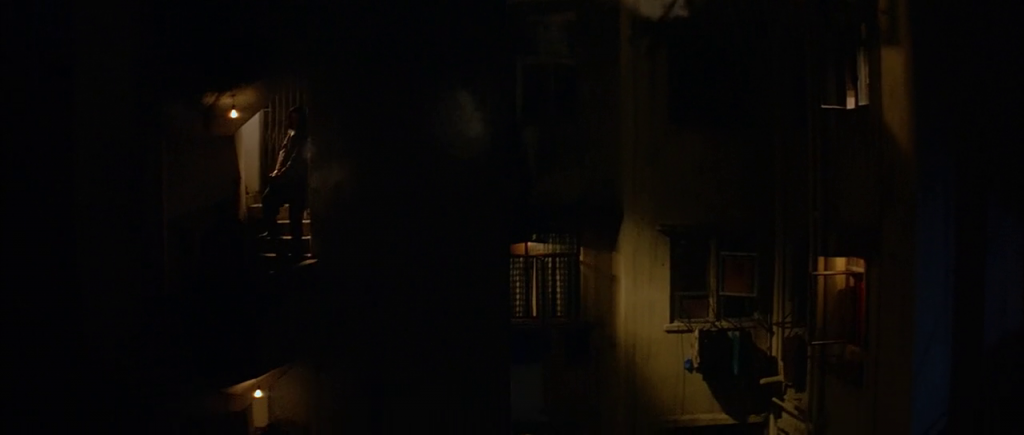

The gunfight that happens when an injured Wo is taken to a triad doctor reminds me a lot of Rear Window, with the entire building in frame as the killers try to escape and trade bullets with their attackers. It’s really beautifully shot and choreographed, with lots of dramatic details, like rain gutters running with blood.

But the sequence that tends to captivate everyone (including myself, clearly) is the one with Sergeant Chen fighting off thugs who have hijacked his convoy. With a cigarette laconically dangling from his lips and his superhuman sharpshooting skills, Sergeant Chen may be the coolest, most baddass motherfucker ever to hold a gun in this movie.

As a person who was living in Taiwan during Richie Ren’s heyday as a cute pop singer, this is absolutely amazing and shocking to me but also makes a kind of weird sense. Richie always had an edge of roughness to him. He’s a southern Taiwanese from Tianzhong, which is basically the countryside where people speak the Hokkien dialect better than Putonghua.

Digression: I am suddenly reminded of one of my Taiwanese uncles, who was exported to mainland China in the early 1990s to administer a beating to someone (long story). Upon arriving, one of his hosts asked him (in Putonghua): “Do you speak Putonghua?”

My puzzled uncle answered (also in Putonghua): “No, I don’t know what that is.”

Host: “What? What do you mean you don’t know what Putonghua is?”

My uncle: “I’ve never heard of it!”

Host: “Then what are you speaking right now?”

My uncle: “Chinese!”

Ah yes, the Lin family. All balls, no brains. To return to Richie, I will also confess that I’ve gone to his concert before and that to this day, his song ”對面的女孩看過來” gets frequent play because my kid loves it, too. Country Hokkien always breeds true.

I’m saying this because who would’ve thought this nice Taiwanese boy next door would end up being so cool? I know Richie was also in another To film, Breaking News, where he was reasonably cool, too, but in Exiled, he’s just awesome, a true boss.

I’ve mentioned before that To, like Miike Takashi, has always had an eye for casting. He’s always been able to identify erstwhile hidden qualities in actors (or even non-actors) and use them as a foundation for what makes their characters cool: Anthony Wong’s melancholiness, Francis Ng’s protectiveness, Roy Cheung’s humour, Lam Suet’s lack of fucks given (has anyone else noticed that his characters are the coldest motherfuckers out of everyone?). In Richie Ren, To identified a core of country boy decency and common sense, and it makes sense that this kind of man gets to survive when the others have no other fate but to die.