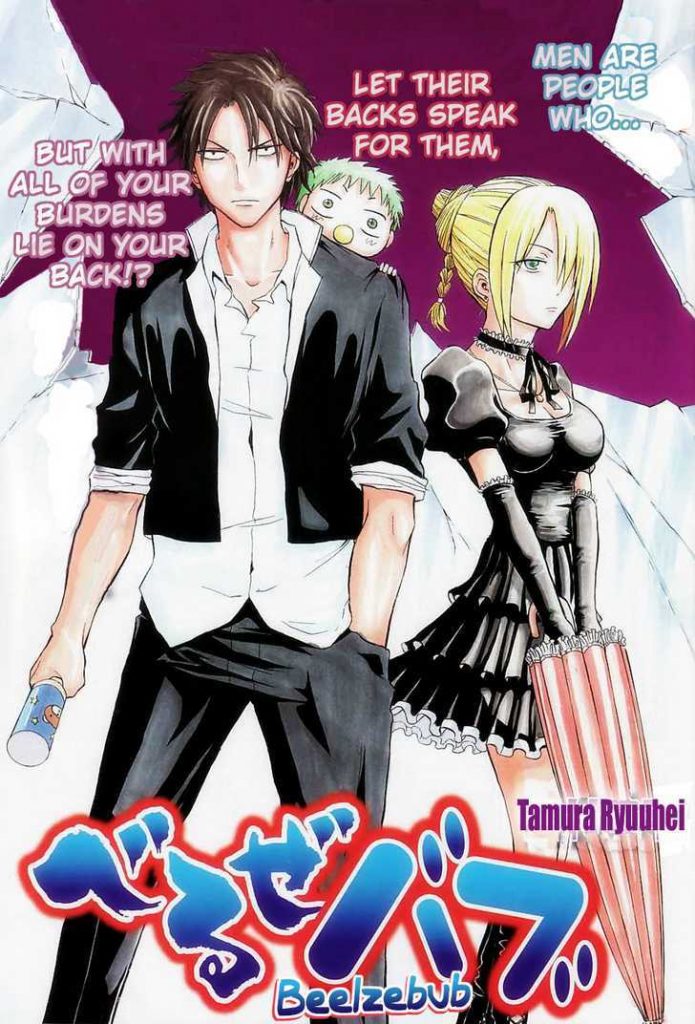

Note: In this installment of Tough Guys, Gangsters, and Delinquents in Asian Pop Culture, I’m looking at the gag-ish delinquent manga, Beelzebub, and how it’s descended from one of the greatest manga of all time, Lone Wolf and Cub. Very many spoilers for both! You can read the previous entries in this series here, if you haven’t yet.

Also, the scans I could find of Lone Wolf and Cub were somehow changed from reading right to left to the Western style of left to right, so hopefully, this doesn’t confuse people too much. Beelzebub remains right to left, as per civilized standards.

It’s been a while since my last entry in the Tough Guys, Gangsters, and Delinquents in Asian Pop Culture series, and I’ll confess that it’s because I was really wrestling with whether or not to include Beelzebub.

This is not to say that I don’t like Beelzebub–I enjoyed it even though it jumped the shark towards the end. However, it’s really kind of a parody of a tough guy sub-genre that has been most popularly embodied by the manga (and later, films) Lone Wolf and Cub, written back in the 1970s by Koike Kazuo, about a ronin who becomes an assassin for hire, and because his wife has been brutally murdered, takes his infant son along with him in his quest for vengeance.

I would like to take a moment to note here that this is the same Koike Kazuo who wrote Crying Freeman, whose Japanese protagonist, Hinomura You, has been brainwashed by the Chinese triad into becoming the ultimate assassin. The reason he’s named “Crying Freeman” is that at the moment of murdering someone, he suddenly remembers who he is and he cries. You has inspired and influenced a huge number of both Asian and non-Asian tragic assassin characters that are still popular to this day, and I’ll be tackling this in a future installment of Tough Guys.

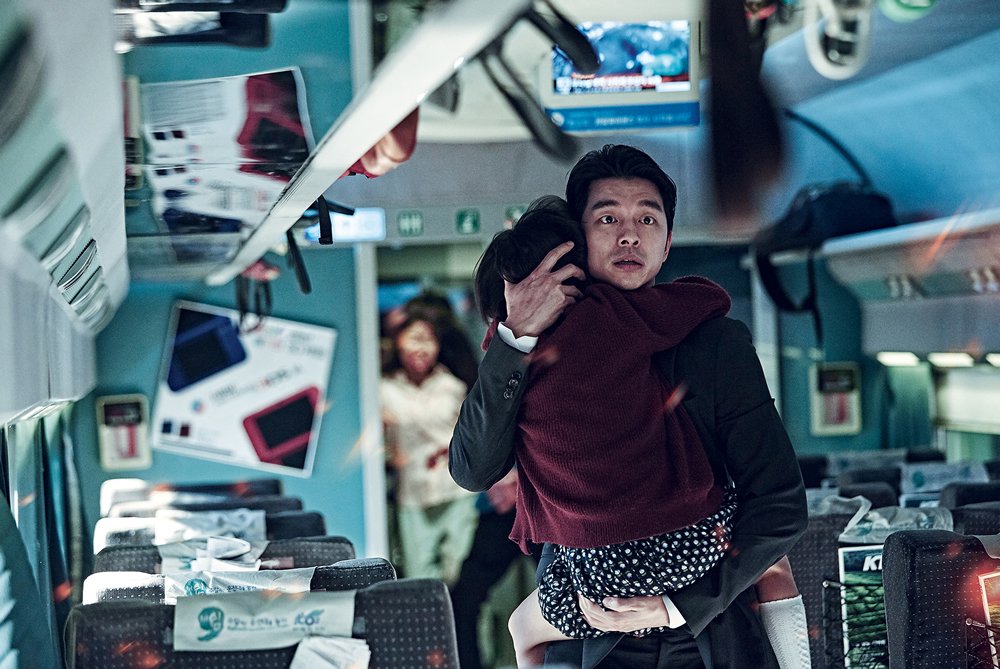

Likewise, Lone Wolf and Cub has inspired tons of other works, including Road to Perdition, an extremely Orientalist and popular American comic that I’d rather not mention by name, and post-apocalyptic stories where a father has to protect his child (Train to Busan comes to mind as a recent example, picture below). It’s also inspired a wuxia short story I’m working on, although this time the protagonist is female.

So since Lone Wolf and Cub is so culturally and narratively important, why did I end up choosing Beelzebub, which, for all its goofy charm, is not even close to how great Lone Wolf and Cub is? Maybe the answer will resonate with other parents, but since I had my kid, I can’t read the manga or watch the films again because seeing kids in danger really distresses me now. As great as the works are, I just don’t have the stomach to read or watch them again without wanting to hold on to my own child in fear.

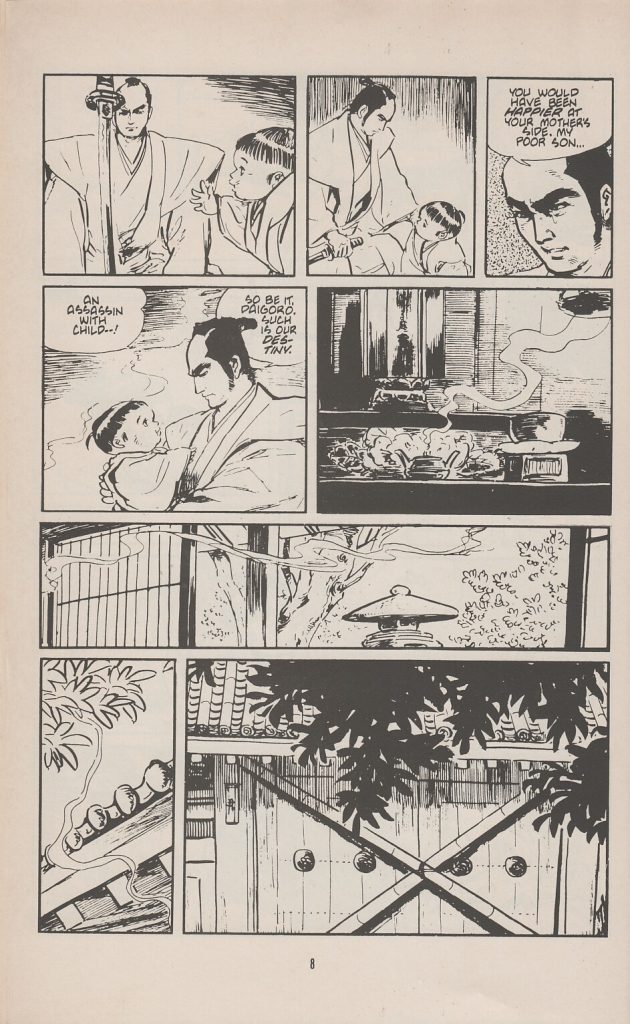

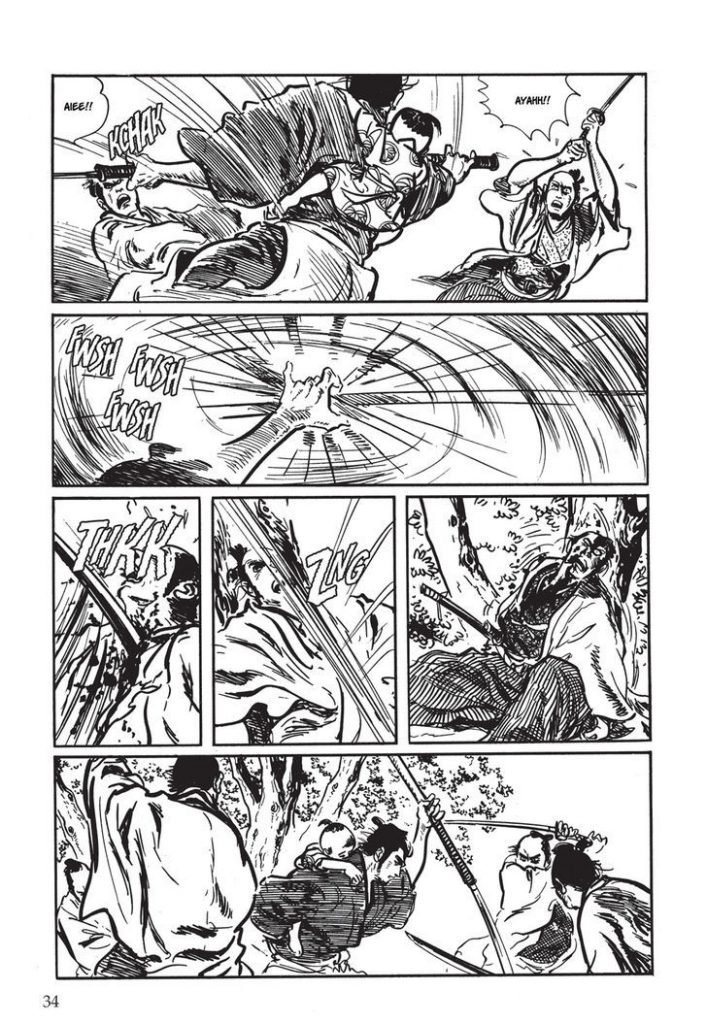

The impact of Lone Wolf and Cub stories lies in the juxtaposition of violence (as represented by the father who must kill to protect his child and/or avenge their dead mother) and innocence (as represented by the child). There’s a kind of tragedy in the fact that a man is forced by the terrible circumstances around him to be a killer and at the same time, care and love for his child and make sure it’s safe in a very dangerous world. It makes me think of a quote from Bleach (Volume 5): “Unless I grip the sword, I cannot protect you. While gripping the sword, I cannot embrace you.”

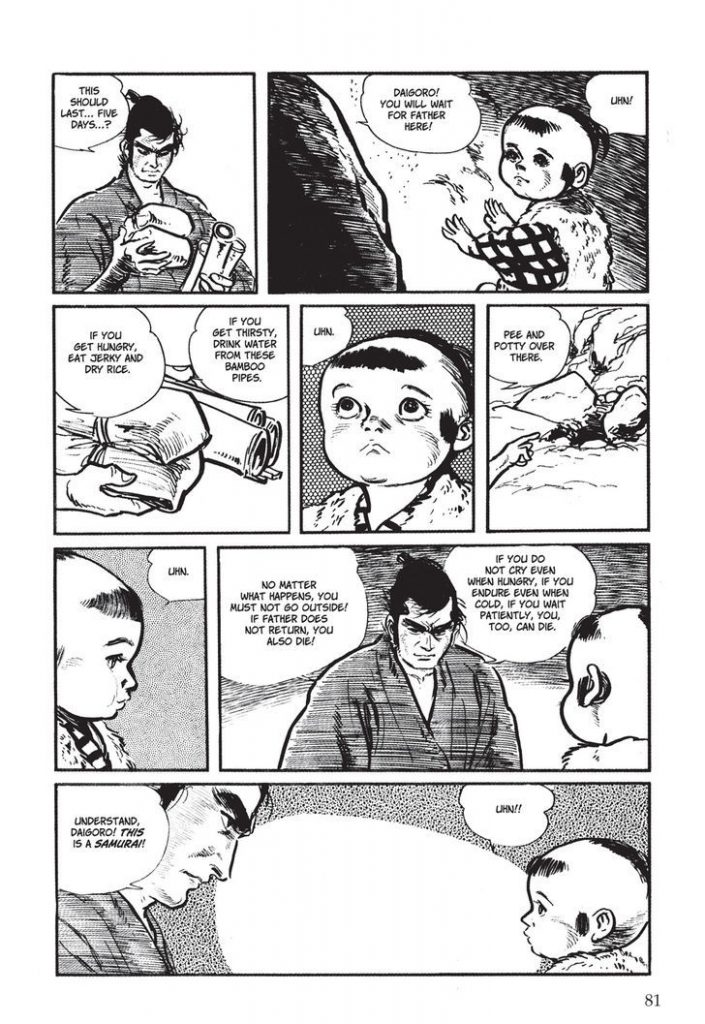

In the typical Lone Wolf and Cub narratives, the father usually struggles to both care for his child while at the same time hardening his child to the realities of a very cruel world. The manga doesn’t hold back when it comes to depicting the horrific things that bandits do, from torture to rape to murder, and it really hurts my heart to think of the Cub not only being witness to these things, but also subject to the laws of bushido, as you can see below.

See what I mean? This is why I can’t read this manga again because I just want to bring that poor child home. This then brings us to Beelzebub, which is easier for my heart to read because it subverts several of the tropes of Lone Wolf and Cub while blending them with many of the delinquent manga tropes.

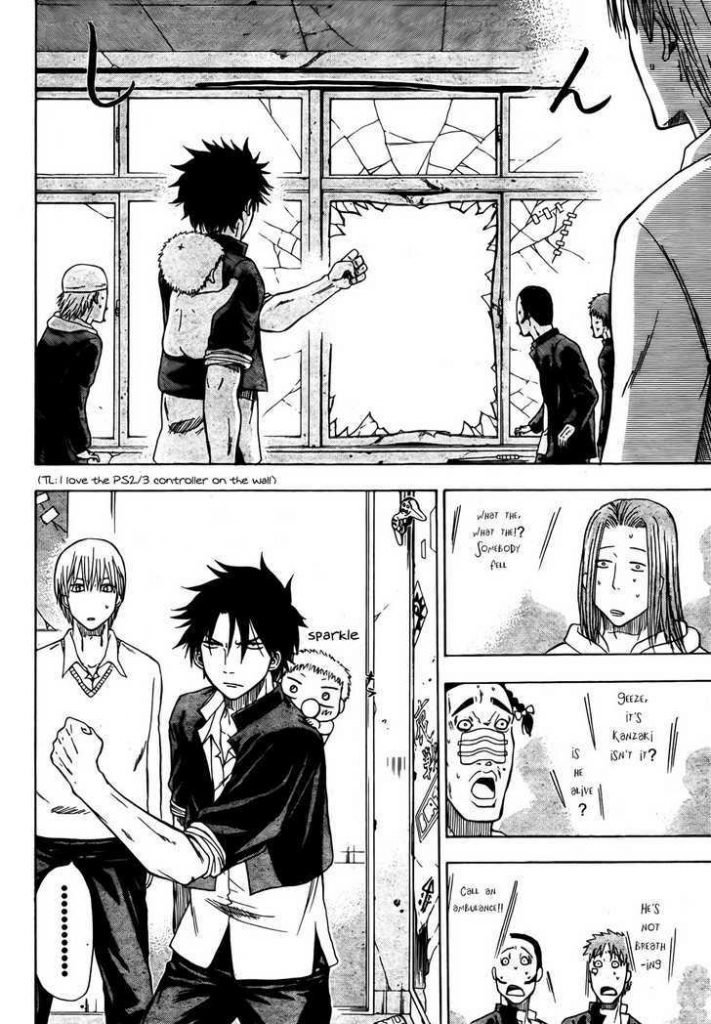

Like Lone Wolf and Cub, Beelzebub presents a situation where someone who is more or less unfit to be a father and yet through circumstances is forced to care for a child, except instead of focusing on the tragedy of it all, Beelzebub chooses to play up the ludicrousness of the situation by choosing the worst kind of person to care for a child: a teenaged boy.

And not just any ordinary teenaged boy: Oga Tatsumi is the worst, most delinquent person in Ishiyama High (by this, it usually means that Tatsumi is a roughneck and asshole, not that he’s a rapist or a thief), and it’s because of his shitty nature that he is chosen by Beelzebub, the son of the Demon King, to be his human foster father. The worse Oga behaves, the more Beelzebub (or Baby Beel), feels attached to him. It’s particularly funny because in Lone Wolf and Cub, both the Lone Wolf and the Cub are referred to as demons because they traffic in death. You can also see some of the visual gags that have Tatsumi fighting while naked Baby Beel clings on to his back, which harken back to the fights where Lone Wolf is carrying the Cub.

While a lot of the tension in Lone Wolf and Cub comes from the potential injury or even death of the little kid, that fear is lessened in Beelzebub because Baby Beel’s demonic nature and background are a huge advantage in ensuring his survival. For example, one of his abilities is zapping Tatsumi with lightning whenever he has a tantrum or is more than fifteen metres away, which means that Tatsumi will do his best not to upset or lose Baby Beel.

Because of Baby Beel’s upper hand, Beelzebub is a pretty good reflection of what modern parenting is like nowadays. I can certainly relate to the panic that sets in when your kid is about have a tantrum, and being struck by lightning is a pretty good metaphor when the tantrum finally starts.

In contrast, Lone Wolf and Cub is set in a time when parents had absolute authority over their children, who weren’t as catered to as they are now. This isn’t to say that the Lone Wolf doesn’t love his Cub, but the circumstances back then meant that children followed their parents’ lead and not the other way around.

Tough guy, gangster, and delinquent stories are basically representative of the fears and challenges of being a man in modern society, and so it’s not unusual that something like fatherhood eventually comes up (although it rarely does in delinquent stories, which mostly deal with the travails of growing up and becoming a man).

Fatherhood is seen as a natural extension of masculinity–you protect the ones you love, including your offspring, and the effort you make defines you as a real man. True tough guys don’t avoid this responsibility, which is where the tragedy of Lone Wolf and Cub comes from: the only way the Lone Wolf can be a good father is also possibly one of the worst ways to be a father.

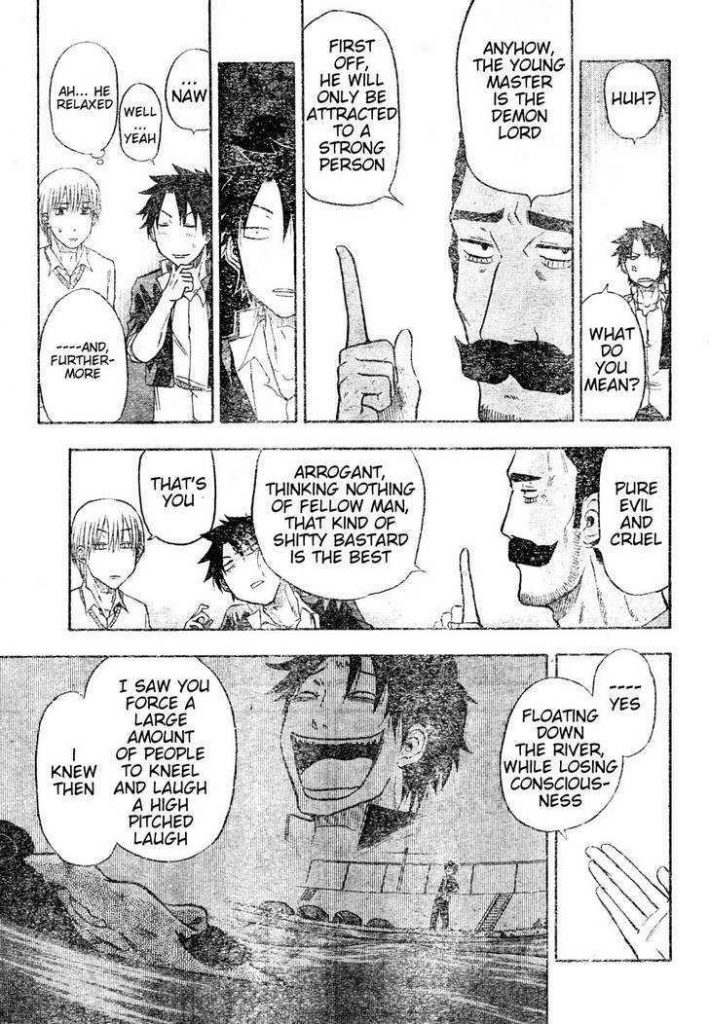

In contrast, Tatsumi initially spends most of his time looking for someone else to pawn Baby Beel off to because he has no interest in looking after a baby and only cares about himself. Unfortunately for Tatsumi, he needs someone who’s even meaner and more powerful than he is, and there just isn’t a person like that around.

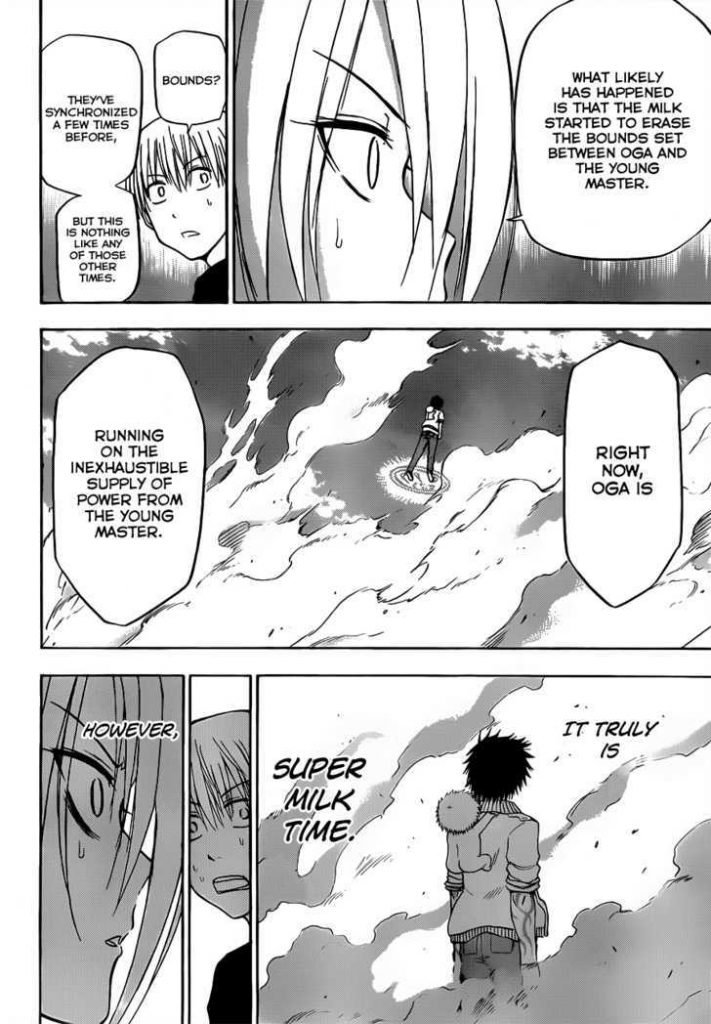

This means Tatsumi’s story arc is about how he grows to become a good parent–it’s not just about being the toughest person around, being responsible for the welfare of your child (even if he is a demon) and learning empathy and compassion are what gives Tatsumi true strength and power and in the end, determines his manhood. It’s also no coincidence that Tatsumi levels up in power when he shares Baby Beel’s milk and thus forms a powerful psychic link.

In this, Beelzebub falls more into the delinquent manga side of character development, where the main delinquent learns that what makes someone truly powerful is their connection to the people around them. For example, every time Tatsumi ends up defeating a rival, they end up becoming friends.

It’s because Beelzebub ends up defaulting to the delinquent-style battle manga side of things that its feel-good ending appears a little abrupt and flat. Tatsumi constantly defeats every Big Bad until he’s the strongest one of all, and it seems like that the cycle won’t end. Kind of like what happened with Bleach: Ichigo keeps leveling up until the battles just become boring.

Nope, I won’t be breaking down Bleach, but I thought everyone could use a little Fukushi Sota.

However, typical Lone Wolf and Cub stories usually don’t bother to develop this arc; most of them either focus on the tragedy of a man taking his child down a path of darkness and vengeance or the tragedy of a man whose only way to protect his child is by dying. And that’s always the penalty for violent fatherhood: the Lone Wolf must always die.

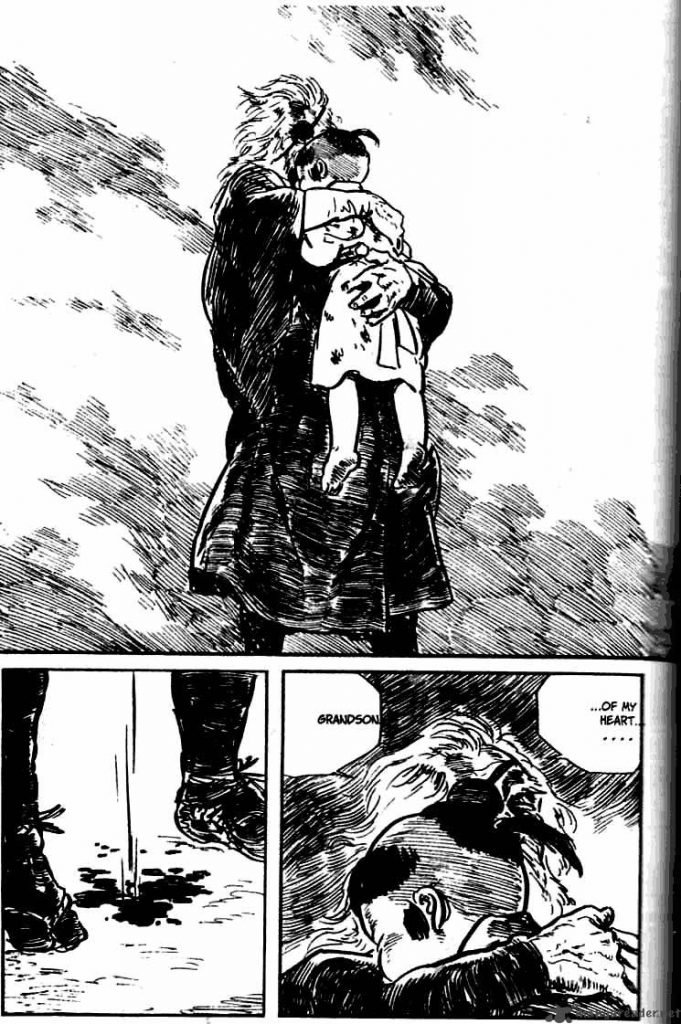

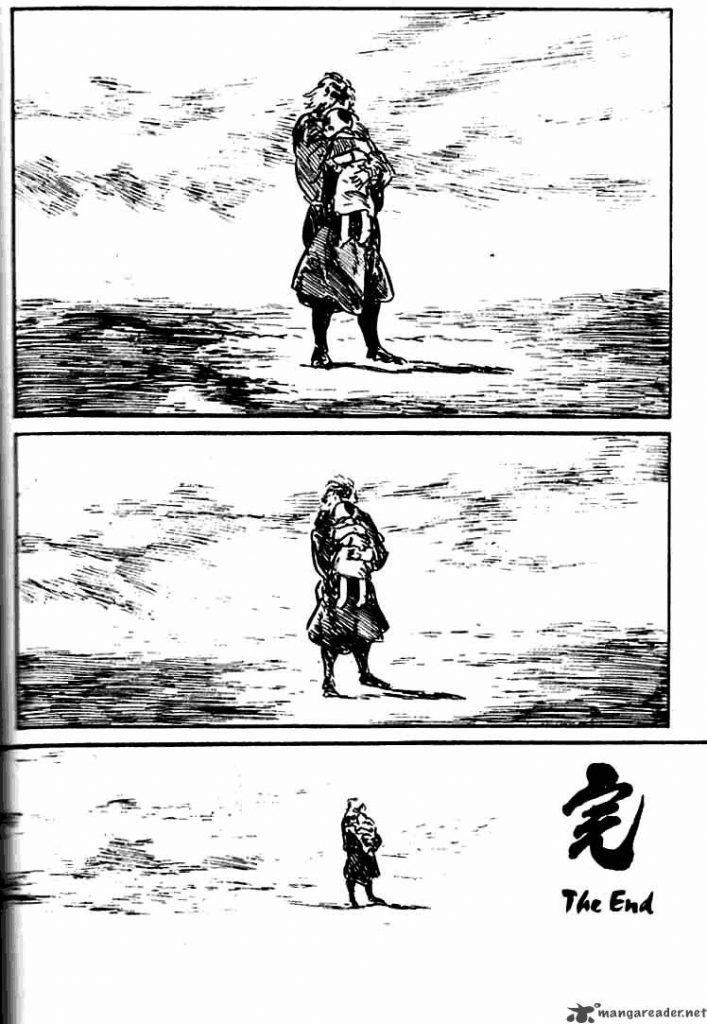

In Lone Wolf and Cub, the Lone Wolf is killed by the man he wanted to get vengeance on. In turn, that man, whose entire family has been killed by the Lone Wolf, allows the Cub to kill him, calling the Cub the “grandson of his heart” and ending the cycle of vengeance.

Even though the Cub is a child of carnage and blood, at the very end, he’s given a second chance through the deaths of his father and another paternal figure.

This ending can be interpreted in so many ways. One is how children are taught to hurt by adults, and the only way to deal with this is to love them regardless of how much pain they bring you because it’s not their fault. It’s also kind of a metaphor for tough guys who become fathers: in order for their children to thrive, the violence in them must be destroyed. The Lone Wolf must die so that the Cub can live, and that is the greatest gift and sacrifice a father could ever make.