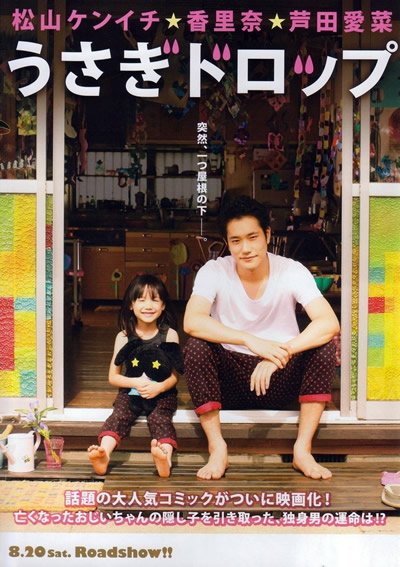

Despite being an admirer of Kenichi Matsuyama’s work, it took me a long time to get around to watching Usagi Drop because a friend of mine who is also a parent told me that he sobbed his way through the movie. I’m glad I managed to watch it, though, because this film is great! Also, please note that this review is strictly about Usagi Drop, the live-action film. I’m not going to refer to the anime or manga at all. There are also lots of spoilers.

A long time ago, I read an article in Sassy magazine about those Mentos commercials that were always on TV in the 90s. The writer said something like, “these commercials have such low expectations that they must be European, or at least Canadian.” The writer added that Americans love big dramas, big stakes–to impress Americans, if you eat Mentos, you should be able to grow wings and fly, not move your parked car from a tight space.

Watching Usagi Drop made me think about the cultural differences between the US and probably the rest of the world. The premise is that Daikichi (Kenichi Matsuyama), a dude in his thirties, ends up being the guardian for his deceased grandfather’s illegitimate daughter, Rin (Mana Ashida), who is six years old. If this were an American film, it would wring maximum I am Sam pathos: there would be a huge custody battle between Daikichi and the kid’s ex-junkie mom who’s now married to a tech billionaire, Daikichi would have a criminal past or secretly be a stripper, Rin would develop cancer or fall out of an airplane…anyway, if you know American films, you get the idea.

I’m so glad to say that Usagi Drop is like a Mentos commercial in that regard. There is no court battle that climaxes with the little kid running towards Daikichi screaming “DON’T LET THEM TAKE ME AWAYYYY” or anything. The most dramatic situation is when Rin skips out of daycare with her friend Kouki, and Daikichi and Kouki’s mom freak out looking for them.

It’s such a relief to watch something like this, where I didn’t feel drained and tired by the end of the movie from all the hysterics and from watching a reluctant father’s growth from a shitty person to a decent one. Daikichi starts the film already a decent person who lives in a nice, clean house. I mean, look at it. Look at that cabinet on the left-hand corner with those three boxes for what looks like different types of tea! THIS IS THE KIND OF GUY THAT YOU MARRY (assuming you believe in the institution of marriage).

He’s not particularly immature, like a full-time gamer, nor does he have man-child hobbies. He’s an adult with an adult’s sense of responsibility. And Rin isn’t forced onto him, he’s the one who decides to take her in because no one else in his family wants to do it. And despite lacking all of the typical pyrotechnics of a film like this, it’s so watchable, and I’m not just saying that because I think Kenichi is gorgeous even with the terrible haircut they gave him.

It’s a quiet movie that identifies something important about parenthood: for most of us, it’s not defined by a dramatic sacrifice but rather by a series of tiny ones that often go unnoticed. One of the moments I really appreciated comes right at the start when Daikichi asks his mom to take Rin and she gets angry and says that it’s really hard to raise a kid and no one knows how much she sacrificed to raise Daikichi and his sister.

Daikichi’s understandably upset by this, and it’s what spurs him to take Rin, and in the end, he does realize that what his mother said is true, and he gets an understanding and empathy for what she had to give up. To care for Rin, Daikichi adjusts his lifestyle, even asking for a job demotion to his company’s warehouse so that he won’t have to work overtime. But thankfully, Daikichi takes it in stride as something he just ought to do and he doesn’t resent Rin for the way she upends his life. His relatives are worried, but they help when they’re needed; the roughnecks at the warehouse rally around him because most of them are fathers too; and he gets sympathy and help from the mothers he meets.

As a single parent (wow, that feels weird to write), it’s nice to come across a film that acknowledges the things you give up without making a big deal out of it. I couldn’t help smiling at this one scene after Rin has moved into Daikichi’s house, which suddenly becomes cluttered with stickers and colourful kids’ stuff. I’m like, yup, I understand, as I look at all the monster truck paintings on my wall and the assorted dinosaur, truck, and animal stickers plastered on my furniture (and occasionally the cats). I used to be so neat that even when I was on drugs or drunk, I would still clean up after myself (I actually think I might have been extra clean whenever I was fucked up because I would wipe the same thing over and over again) and now I am just resigned to a cornucopia of toddler-related shit spilling out everywhere.

I know the film has a rose-coloured filter but it’s such a reassuring fantasy that things will be okay, and sometimes, parents need to be reminded of that. I also appreciate that the film brings up the idea that mothers do make sacrifices and that they feel all kinds of things about it. We learn that Daikichi’s mom loved her job and gave it up and his female co-worker has also made sacrifices to her career. Even Rin’s mother, Masako (Mayu Kitaki) gets a fairly well-rounded treatment. Unlike the other women, Masako chooses to sacrifice her child instead of her career. She’s a mangaka and just when she got a good job, she got pregnant. Although Daikichi thinks she’s a horrible person for claiming that she doesn’t think of Rin as her daughter, we get to see that she does have lingering regret and a desire to see Rin happy.

Along with Daikichi’s work-related sacrifices, Masako’s scenes highlight how modern capitalist society makes it difficult to be a parent or hell, even be a human being. I just wish we didn’t only see this whenever the story is focussed on a man, although I get that the film’s charm rests on seeing a clueless, well-meaning dude care for a little girl. It was an extremely good move to cast Kenichi, who has the same liquid-eyed Bambi quality of a young Keanu Reeves. There’s a softness to Kenichi that feels like he was either very loved or very hurt as a child, and it serves him well next to a cute little kid who could easily steal scenes from him.

I don’t know if any other actor could have pulled off Daikichi because the character would get really boring fast, but Kenichi’s quiet eccentricity makes him extremely watchable. He turns even an Internet search for Masako into a subtly comic scene with the contrast between his outrage on Rin’s behalf and his actual, shy behaviour.

There are a lot of moments in this film that I really enjoyed, like when the kids run away from daycare to visit Kouki’s father’s grave, and they meet a young dude on the way (played by porcelain doll-looking Go Ayano), whose reaction is so typically dude-ish. Instead of asking them if their parents know that they’re out on their own, he just shrugs and leads them to the graveyard.

The scene that really moved me the most, though, happens after Rin goes down with a fever, and Daikichi doesn’t know what to do until Kouki’s mom helps him out. Later on, while Rin sleeps off her fever, Kouki’s mom gives some reassurance to Daikichi, who is feeling shitty about his helplessness. She tells him that kids know who’ll take care of them, and the fact that Rin clung to Daikichi when she was sick is a sign that she trusts him and believes that as long as he’s around, everything will be fine.

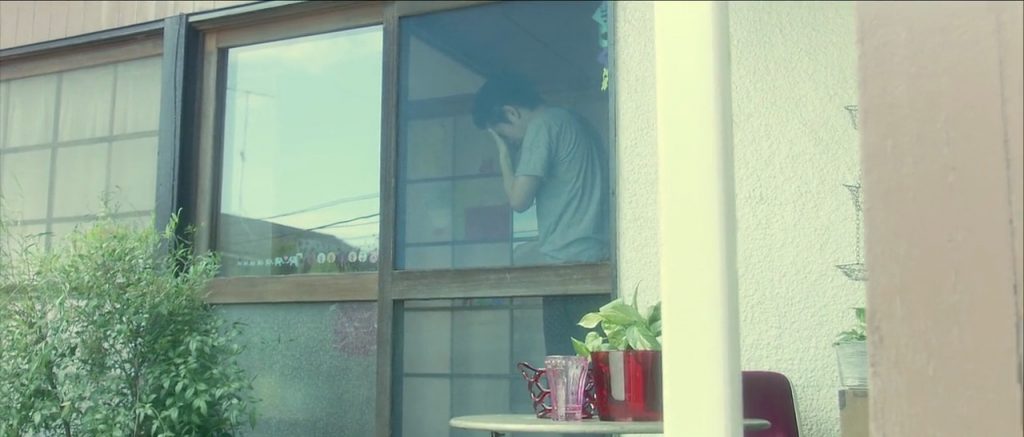

Without any scenery-chewing, Kenichi manages to look guilt-stricken, relieved, happy, worried, grateful, and exhausted, all at the same time. It’s hard not to tear up, especially when he excuses himself to sob quietly in a corridor.

I think most parents would understand.

Here’s the trailer below: