Hong Kong’s cha chaan teng teahouse restaurants are known for their soy sauce-inflected Western cuisine, and typical menus offer a high density of deliciousness per calorie along with middling nutritional value and low prices. The good ones are also notorious for never having enough space for customers. At peak hours, strangers are often expected to sit with each other or acquiesce to impromptu seating arrangements, like the time I was offered a stool and a foldable mahjong table in a hallway by the toilet that had rags strung overhead like bunting.

Anyone who has ever eaten at a cha chaan teng would have recognized the significance of the table politics that occur a few minutes into Johnnie To’s 2003 crime film, PTU (Police Tactical Unit). Ponytail (Chiu Chi-shing), the son of a triad gang leader, and his young followers enter Fong Wing Kee hotpot restaurant, only to be given a table in the back of the busy restaurant.

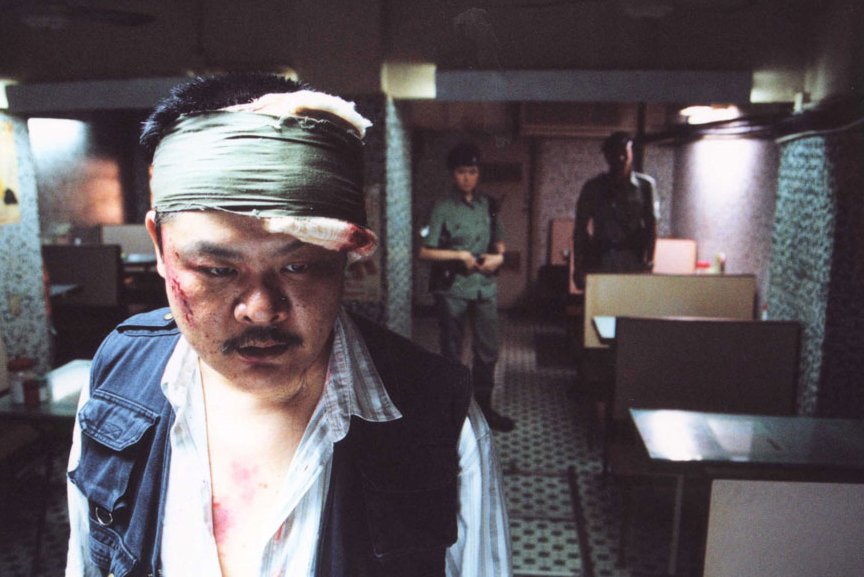

When he’s dripped on by a leaky air-conditioning unit, Ponytail rebels against his assigned table, and asserting their status as gangsters, the triad group forces a lone, Hawaiian-shirted diner to change tables with them. Unfortunately, the rule “Do unto others what you would have them do unto you” kicks in instantaneously when Sergeant Lo Sa (Lam Suet), head of the District Anti-Triad Squad enters the restaurant. Sergeant Lo contemptuously seats himself at Ponytail’s table, forcing the group to retreat to their original table, while poor Hawaiian Shirt is in turn sent to the Siberian outskirts next to the steaming kitchen.

In revenge, Ponytail sends his goons to mess up the officer’s car, leading to a chase that ends badly for Sergeant Lo: he’s not only beaten up by the goons, he also loses his gun in the process. But unfortunately for Ponytail, the golden rule kicks in once more as he sits alone and vulnerable in Fong Wing Kee—Hawaiian Shirt gets up and stabs him with a machete before casually exiting through the kitchen.

People often bring up this scene as an example of To’s signature ability to create a precarious balance between humor and tension, and it’s also noteworthy for encapsulating how characters in the film struggle to wrest control of the narrative. To makes it so plain that it’s practically meta-commentary when Ponytail, Sergeant Lo, and Hawaiian Shirt, who use similar cellphones with similar ringtones, keep answering their phones only to find out that it’s the other person’s phone ringing and that someone else has control of what the audience hears.

The larger narrative of Ponytail’s death and Sergeant Lo’s beating end up drawing in not only Sergeant Lo’s fellow officers, but also two rival triad gangs and an unsuspecting group of mainland Chinese robbers. After Sergeant Lo discovers that he’s lost his gun—a major disciplinary infraction—he asks Sergeant Mike Ho (Simon Yam) for help. Sergeant Mike, who is leading a police tactical unit on patrol, agrees to help search for the gun as his unit walks through the Tsim Sha Tsui district. However, the two agree on a deadline of four AM—if it’s not found by the time they all clock out, Sergeant Lo will report it to their superiors.

As the overnight search for the gun takes place, narratives jostle for domination, from the triad gangsters who want to blame each other for Ponytail’s murder to Mike’s attempts to deflect Inspector Leigh Cheng (Ruby Wong) from the Criminal Investigation Division, who is convinced that he and his unit are up to no good. In PTU, everyone has a story they want to make sure prevails because if enough people agree to believe it, it becomes the truth. And what seems to persuade people to come to an agreement is a narrative neatness—a story that is free from ambiguity and loose ends.

Throughout the film, To reminds us of the reasons and ways narratives can be subsumed. When Sergeant Mike and his team find Ponytail’s cousin at a dimly lit video game arcade, Officer Wong (Raymond Wong) somehow manages to accidentally turn off the CCTV cameras as Sergeant Mike plants drugs in the cousin’s pack of cigarettes. In a major flex, Sergeant Mike does it right in the cousin’s face, both as a warning and as an assertion of dominance—his story has more power than the cousin’s because more people are likely to want to believe him. It’s less of a challenge to accept that a gangster has drugs on his person than to believe that a police officer is keeping an envelope of drugs ready to intimidate someone who isn’t even a suspect.

The same narrative domination appears again when Sergeant Mike and the unit catch a thief and proceed to give him a beatdown when he initially refuses to snitch on his fellow gang members. In another example of narrative manipulation, the officer in charge of the beating takes off his boots order to avoid being identified through the police tactical unit’s distinctive boot prints. When the asthmatic thief stops breathing from the repeated kicks to the ribs, the officers panic and Sergeant Mike quickly performs CPR. As soon as the thief starts breathing again, Sergeant Mike quickly tells him, “You collapsed on your own.”

Still gasping as he sucks air through his inhaler, the thief agrees “Yes, it was all me” before confessing everything that he knows about Ponytail’s murder. As the police officers help him to his feet, plying him with solicitous questions about his health, Sergeant Mike calmly states once more, “We’re not responsible for your asthma attack.” The thief, understanding the bargain that must be struck, replies, “Not at all, it was all my fault” and he’s let loose by the police with his packet of stolen credit cards.

As the search for Sergeant Lo’s gun continues, the other characters are also caught up in their own narrative compromises and conveniences. Bloodied from his beating by Ponytail’s goons, Sergeant Lo insists that his injuries are due to a nasty fall, an explanation his suspicious superiors are forced to accept because they don’t have a choice. He purchases an airsoft gun as a cover for his missing one, and later becomes a reluctant witness and accomplice to the rival triad gangs who want to insist on their versions of the conflict that results in Ponytail’s murder.

And as she and her team cruise through Tsim Sha Tsui to uncover what everyone else is up to, Inspector Leigh picks up a junkie from a club and proceeds to have him beaten for information. Unlike Sergeant Mike, Inspector Leigh makes no attempt to overlay a different narrative onto this occasion of police brutality. We discover that it’s because the junkie is actually an undercover police officer who needs the narrative credibility of police harassment.

Despite all of her talk about following rules and procedures, Inspector Leigh also understands the need to impose a clean narrative that pushes away the need for questions. She accidentally drops her gun during a shootout and is forced to cower inside her car while her fellow officers attempt to subdue several criminals. When the dust clears, Sergeant Lo tells her, “Madam, you might as well fire a couple of shots so that it looks good on the report.” Inspector Leigh follows his advice while the other officers look away. None of these actions come from malicious intent; it’s simply more convenient to add details to make the story more believable.

It makes sense that a film set in Hong Kong would be concerned with how narratives get lost or squeezed into a larger, more agreeable one. Hong Kong is a city whose own narratives have been under siege since it was seized from the dying Qing empire by the British. Faced with local riots due to corruption and abusive labor practices in the 1960s, the colonial government made a concerted effort to create a Hong Kong narrative separate from that of mainland China. The multitude of narratives within the city were flattened into the Orientalist images we now associate with Hong Kong—Chinese junks sailing in the harbor and “modern” young women in Westernized cheongsam dresses.

Just as Sergeant Mike and Ponytail’s cousin understood that narrative dominance lies in the number of people willing to believe a story, the colonial administrators knew that they had to reframe Hong Kong’s past to appeal to Western preconceptions. It’s easier to avoid the uncomfortable questions of Hong Kong’s history when you can bundle it up in a neat, colonial narrative.

In only a couple of decades, another dominant narrative of Hong Kong would emerge in the West. The neon-lit streets and trench-coated killers of 1980s Hong Kong cinema influenced foreign films like Blade Runner and Ghost in the Shell and entrenched a noir exoticism that still lingers. However, by the time To made PTU, the city’s vernacular had shrunk into the neon signs with gibberish Chinese and narrow, crowded streets under looming buildings of video games like Battlefield 4 and Call of Duty.

Although PTU is set in Tsim Sha Tsui, the inspiration for these imagined landscapes of Hong Kong, To chooses to focus on empty streets rather than alleyways filled with claustrophobic masses of people. Even the table scene takes place in a location that doesn’t simply serve as a backdrop but exists as a living context that has its own rules of behavior. PTU takes a psychogeographic approach to the city and peels away the surface layer of exoticism. And without the baggage of this visual shorthand, the film allows the complicated and troublesome stories that don’t quite fit in to come forward.

In some ways, even as PTU follows an evening-to-dawn frame, it implicates the artificiality of this form as culpable in creating one streamlined narrative to the detriment of other narratives. The audience expects that by sunrise, all loose ends will be tied up, an Occam’s razor explanation will be provided, and no further questions need to be asked. We want to go home from the cinema with a sense of satisfied resolution—things make sense and they end in a way that doesn’t challenge how we expect the world to work.

To practically spells this out at the beginning of the film: we see Sergeant Mike’s police tactical unit riding in their armored personal carrier on their way to start their overnight patrol. As they listen to the radio, a report comes on that a fellow officer has been shot and killed during a robbery (a crime that incidentally has its own Chekhov’s gun moment later and is tidily resolved).

Officer Wong scoffs at the heroic narrative they’re hearing from the radio; the dead officer was a former partner who had been such a coward that he hadn’t ever pulled out his gun. The other officers chime in with sniggering jokes at the dead officer’s expense until Sergeant Mike snaps at them to be quiet and tells them that everyone in a police uniform is one of their own, diminishing the nuances that Officer Wong’s story offers. Other stories don’t matter as much as the one that keeps them united.

Affirming this, Sergeant Kat (Maggie Shiu) tells the unit: “No matter what happens, the important thing is to go home.”