Presenting one of the most imitated films ever: Sex and Fury! As usual, there are more spoilers here than hanafuda cards, so be warned! To read previous instalments of the Tough Guys, Gangsters, and Delinquents in Asian Pop Culture series, click here.

It won’t surprise anyone that there is a strong link between sexual arousal and fear. As this article in Psychology Today states, “Something about the state of fear or anxiety, in other words, appears to make many of us more likely to experience feelings of sexual attraction towards other people.”

In my breakdown of Battle Royale for this series, I wrote about the “sexy killer schoolgirl” trope, which is a pretty good example of fear and arousal encapsulated in one person. People like the idea of “taming” someone dangerous–as I’ve also touched on in Exiled–and the contrast between the expectation that a schoolgirl would be innocent and the reality that she could kill you is also really attractive to many people.

But it’s really not just schoolgirls. All you have to do is put weapons in the hands of a conventionally attractive, feminine woman and make her wear revealing clothing (or better yet, she doesn’t have to wear anything at all). Sexploitation films capitalize on this contrast: in societies where women are expected to be virtuous, demure, and helpless, a dangerous woman hits all the right fear and arousal buttons.

In Japan, the sexploitation genre saw its peak in the 1960s and 70s with pinku eiga or pink cinema, and Toei became the studio most famous for its “pinky violence” films, which combined a lot of bloodshed along with softcore pornography. It’s possible to see this as a reflection of what was going on in the West, where the rise of the women’s movement saw an increase in sexploitation films, as well. A lot of these films have what I guess we could call strong female characters who seek revenge on the men who’ve wronged them, which is obviously a reflection of what was going on in society, but dressed up in sex and gore to attract audiences.

Released in 1973, Sex & Fury or Story of Delinquent Female Boss: o-Chō Inoshika is probably one of the most famous pinky violence films, thanks mostly to the charisma of its star, Ike Reiko. Ike plays Inoshika Ochō, a tough-guy thief and gambler–clearly the inspiration for Michiko in God of Gamblers—

who wants to avenge her father’s death, rescue the sister of a fellow gambler, and help out Shunosuke (Naruse Masataka), a dude whose hairstyle I had in the 1990s, avenge his own father’s death. Oh, and also save the country from Western imperialists.

We’ll get to this later, but first, I find it fascinating that in tough guy movies, even in this one, with a female protagonist, it’s always murdered fathers who need to be avenged. Doesn’t it seem like women are only avenged if they’re wives or daughters but hardly ever if they’re mothers? With wives and daughters, it’s clearly because they’ve been considered property for a large part of history. When they’re murdered, honour culture dictates that it’s an insult to a man’s pride that his property has been fucked with, so he needs to show that he can take back his honour.

Mothers tend to represent sacrifice and unconditional love, so I suppose their deaths are kind of unremarkable. Fathers, on the other hand, are linked to honour, and their deaths are an attack on a tough guy’s identity and character, so they must be avenged. I also wonder if there’s an Oedipus complex-type situation going on here for sons; the father must die so that the child can become an adult in their own right, but someone else has to do the killing so they can remain the good guys.

Ocho’s father is a police detective investigating high-level government corruption, which leads to him being murdered by three mysterious figures in front of little Ochō. Before he dies, he grabs three cards from a hanafuda gambling deck as a clue to the identities of his killers, and we’re left to infer that this is the reason Ochō becomes a professional gambler.

The death of Ochō’s father kicks off one of the most stylish and coolest opening credits of a film. Toei films are already generally fantastic to look at, and this film may be one of the best-looking ones. It also has a ton of fight scenes that have been copied by films all over the world, as well as fantastic moments like nun bodyguards.

The story then officially starts with a grown-up Ochō, by this time a professional thief and gambler, in 1905, which is around the time Japan emerged victorious from the Russo-Japanese war. It was an exciting moment for many Asian countries–even China–who had their own anti-colonial revolutions and struggles.

The choice to set the film in this time period is pretty significant since the 1960s saw the Anpo protests against the Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security between Japan and the United States, which many understood as an example of US imperialism and aggression. Although the protests had wound down by the time Sex and Fury came out, many of the anti-imperialist feelings were still lingering in Japan. As I’ve mentioned before, stories set in the world of gangsters and tough guys are often ones of resistance to colonizers and the corrupt governments who enable them.

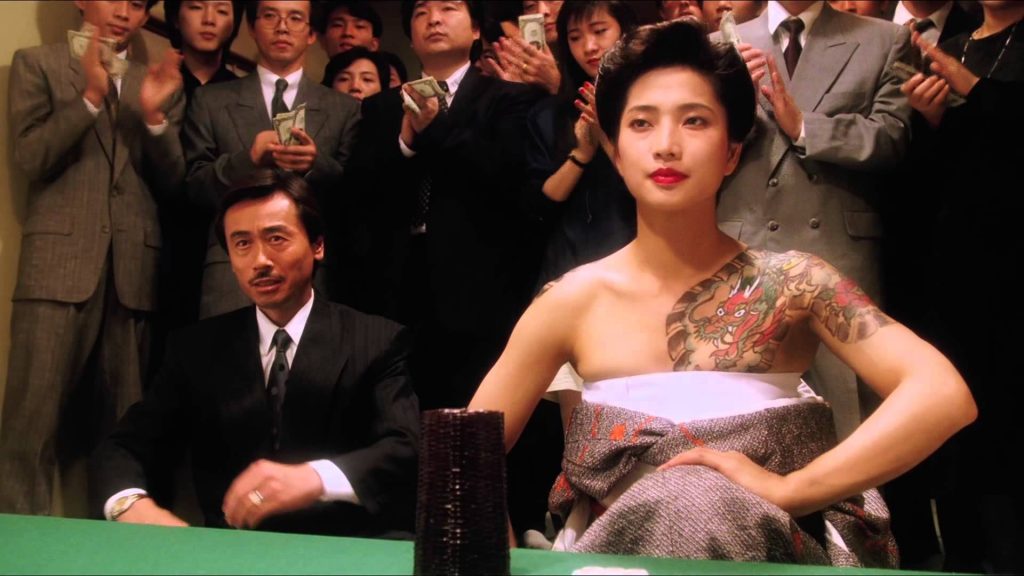

Ochō’s search for her father’s killers leads her to a pair of cruel and corrupt government officials, Kurokawa Yoshikazu (Kawazu Seizaburo) and Iwakura Naozo (Nawa Hiroshi), both former yakuza with tattoos on their backs of two of the hanafuda cards that Ochō’s father had held onto.

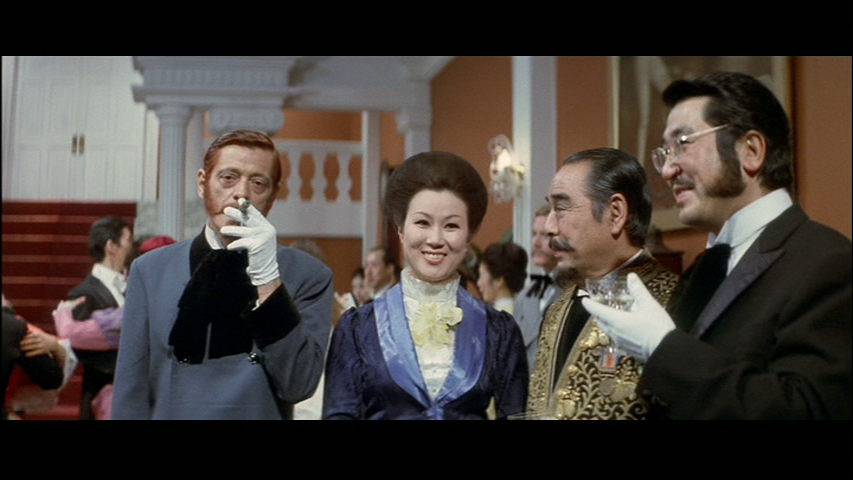

The two criminals have turned into politicians and are hoping to take control of Japan with the help of the British. At least, I think they’re supposed to be British except Guinness (Mark Darling) has an American accent (I’m pretty sure he’s actually an English teacher who got roped into this movie) and Christina (Christina Lindberg) is Swedish. Anyway, they have an ulterior motive for helping Kurokawa and Iwakura: they are planning to destabilize Japan by instigating another Opium War.

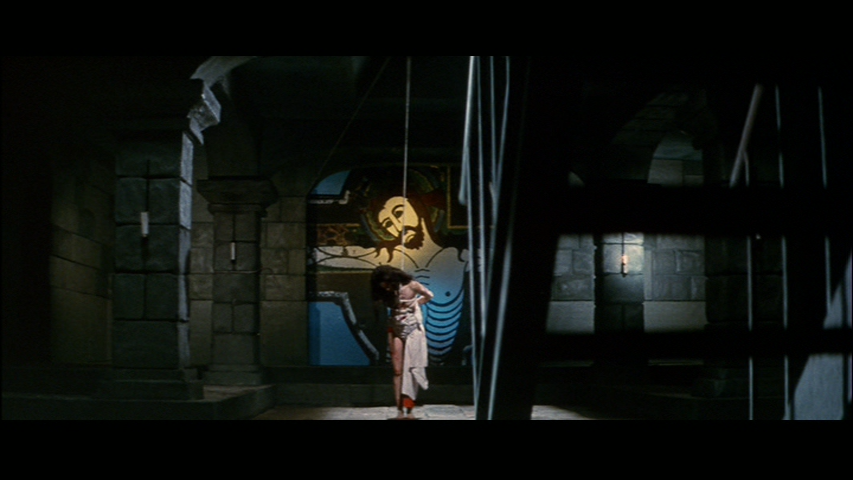

Yeah, it’s a pretty flimsy pretext to include white people in a film for the exotic factor, and especially in the case of Christina, who has the most number of sex and nude scenes in the film. I figure the filmmakers were making the most of the belief that white women are more sexually available than other races. Just look at the Japanese poster, where Lindberg’s picture is much more prominent than Ike’s, the actual star of the film. And also check out the painting in this scene where Guinness is telling Christina to sleep with Kurokawa to seal the deal. It’s a white woman dancing with a faun (who are usually known for their lustful nature).

On top of the Opium War stuff, there’s another twist: Christina is the former lover of Shunosuke, who is after Kurokawa and Iwakura for not only murdering his father but also for being corrupt officials. She was once a dancer (the implication is that she was a stripper) and became a spy whose duties include gambling and prostitution in order to return to Japan to find Shunosuke. Yeah, it doesn’t make much sense.

Just as in other films, the elite class in Japan is portrayed as being complicit with Western imperialists; they live in Western-style houses and wear Western-style clothing and don’t have any patriotic love for Japan, in contrast to the kimono-wearing Ochō and Shunosuke.

Shunosuke is such a patriot that he abandoned a pregnant Christina, and just in case we don’t get it, she tells him that she knows his country is more important than a woman. And yet, of course, she still loves him and wants to have another chance with him. No one ever speaks of what happened to the baby.

Unlike the men, who have power and the nation on their minds, women are mostly doing things out of their own personal interests. Christina immediately betrays Guinness to help Shunosuke, and even Ochō’s saving of Japan is only a byproduct of her revenge quest.

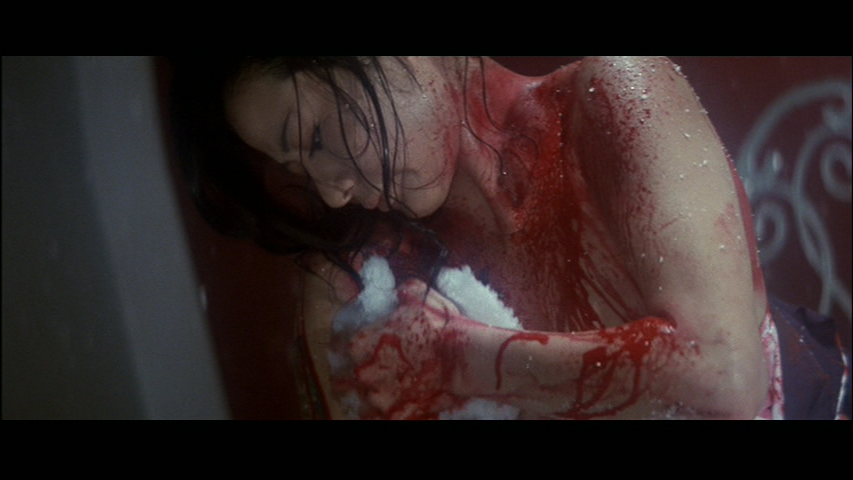

Rape is a big element in many of these films, and oftentimes, it’s the motivating reason for a protagonist’s revenge spree (thank God not this one). I suppose it’s understandable, given how rape is portrayed as the worst thing you could do to a woman, but the titillation that usually accompanies its portrayal in these films makes for a rather discomfiting experience. There’s almost an implication that it’s okay that the women are objectified and abused because they get to kill people after.

Although she’s constantly sexualized, Ike’s natural self-possession and lack of self-consciousness sort of tempers the ickiness of the sexploitation. She doesn’t simper like the other female characters, and she plays Ochō as a straight tough guy. In fact, Ochō is given a lot of typically masculine tough guy attributes, from her expertise in gambling and brawling to her female friends and peers–fellow pickpockets and thieves who live in a happy household that’s females only (with the exception of an emasculated houseboy comic relief sidekick). She even gets the Christ symbolism after she rescues her friends from a disco-lit torture chamber and sacrifices herself for them.

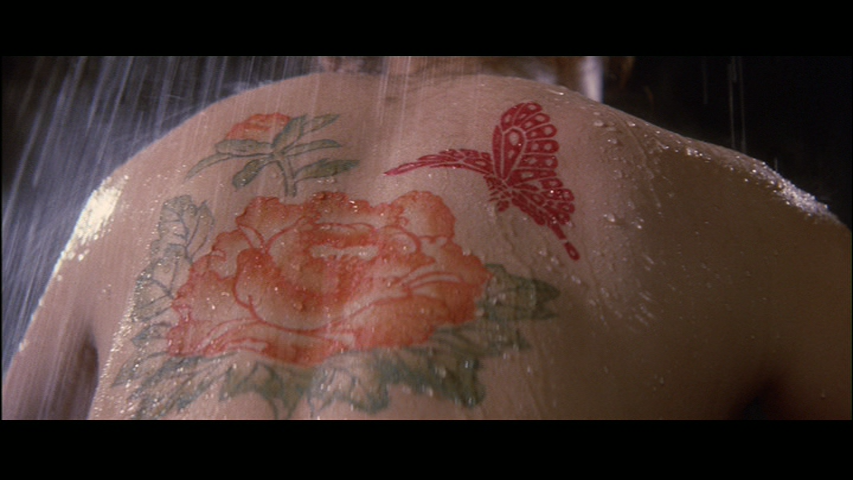

It’s during her torture that Ochō discovers that one of the three murderers is her own mother, who tries to rescue her and ends up dying for her efforts. This death doesn’t cause any grief because that’s what mothers are for, after all, but I did find it intriguing that when Ochō uses a hanafuda razor card to cut loose her ropes, it’s similar to the peony and butterfly design that her mother has tattooed on her back.

In the end, it’s left up to Ochō to deal with the bad guys as both Christina and Shunosuke end up killed after being caught in the dumbest trap ever. After she’s dispatched all of the criminals, Ochō stops to clean the blood off her tattoo with snow. It’s a moment full of rather heavy-handed symbolism but I dig it. There’s the pure snow washing off the filthy blood over Ochō’s tattoo of a white chrysanthemum (a symbol of death and grief). Ochō has finally avenged her father and it’s all over.

In the final scene, the falling snow turns into hanafuda cards fluttering to the ground as Ochō walks away, a callback to how we see her in the beginning. It’s an ending worthy of a wandering swordsman and tough guy who departs the way she has arrived: like a badass.