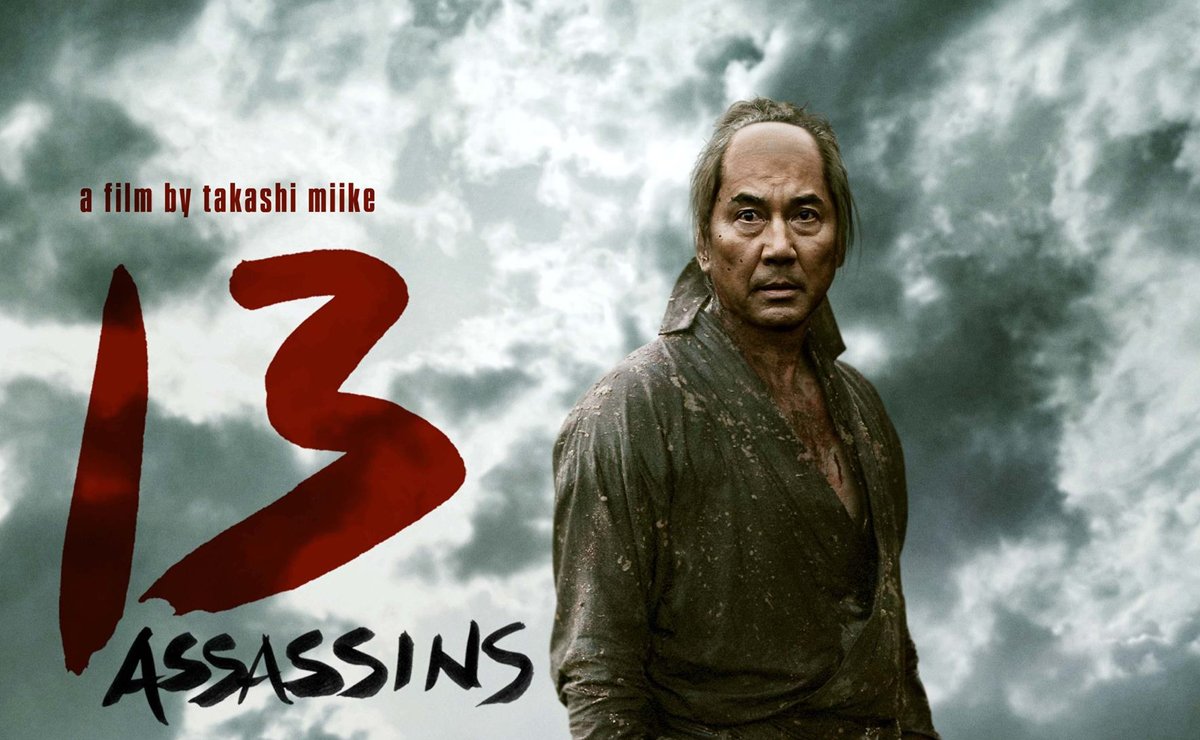

Note: As a companion piece, I suggest reading this fantastic article on how the idea of “bushido” and the “art of the sword” is completely bullshit. This latest post in the series Tough Guys, Gangsters, and Delinquents in Asian Pop Culture looks at what it means to be samurai and/or a man in Miike Takashi’s world of 13 Assassins, and the spoiler level is pure gore.

I don’t know if there has ever been any director other than Miike Takashi who has made me say “Good Lord” so many times during a movie. At this point in Miike’s career, there’s no need to introduce his oeuvre, except to say that while doing some research for this breakdown, I was shocked to find out that he’s ethnically Korean. I feel like that explains a lot about the type of characters that recur in his movies, but at the same time, I’m so surprised that he’s assimilated so much into Japanese society that he’s never asked about being a Zainichi.

Like Johnnie To, Miike has a wealth of films perfect for this series, but I decided on 13 Assassins since it’s easily available to watch and it’s a remake of a well-known chanbara film made in 1963, around the same time as Kurosawa Akira’s Seven Samurai (with which it shares many elements, most importantly the “few versus many” odds) thus providing it the classic themes of its genre.

Chanbara or “sword-fighting” films are a subset of jidaigeki or period dramas. Jidaigeki are usually set during the Tokugawa shogunate, which lasted until 1868, and in chanbara, there’s usually a lone swordsman with incredible sword skills who ends up killing a lot of people. And like all tough guy films, chanbara tend to be centred around the idea of revenge or justice, particularly against corrupt institutions and systems, usually represented by a figure of authority or power.

In 13 Assassins, this figure is Lord Naritsugu, played by Inagaki Goro, which may not mean anything to those of you who are young’uns but GOOD LORD, Inagaki Goro from SMAP!

Kimuya Takura may have been the most famous one–many will remember him from the J-dramas Long Vacation, which put “plays piano” on the list of necessary boyfriend attributes, and Love Generation, which made a crystal apple a de rigueur decorative element in many a young person’s bedroom. But choosing Goro is a casting move on the same level as casting Lee Yeong-ae in Sympathy for Lady Vengeance. Miike explained during a press conference at the Venice Film Festival:

And it’s true. Inagaki is incredible as Lord Naritsugu. Instead of overplaying Lord Naritsugu as a psychotic beast, Inagaki allows the character’s sadism emerge from boredom and curiosity, using his safe, almost bland prettiness as a foil to his horrible cruelty. Lord Naritsugu’s position allows him to have anything and almost anyone he wants (something probably familiar to Inagaki, as well), and the ennui of it all makes him feel dead inside. We don’t even really see him enjoying his cruelty–he’s doing these terrible things because there simply is nothing else worth doing. It’s only through other people’s pain and deaths that he can sort of feel alive, and this theme–that only suffering and death make life worth living–runs through the entire film.

Lord Naritsugu is based on a real person, Matsudaira Naritsugu, who was known to have killed a three-year-old child who annoyed him, but many of the other details like his excessive cruelty were probably taken from other historical figures during the Edo period.

After the opening scene, which shows a samurai committing seppuku in protest of Lord Naritsugu’s cruelty, I was bracing myself to see some Miike-style gore, but he’s actually quite restrained in this film. Aside from a few decapitations, the only truly Miike-esque bit of grotesquerie is one of Lord Naritsugu’s victims, a young peasant woman whose father rebels against Lord Naritsugu’s harsh taxes. Lord Naritsugu tortures, horribly mutilates, and repeatedly rapes her before casting her out to die. We thankfully don’t see any of that happen, but our eyeballs are slapped awake with her naked, limbless body, and the scene where she writes with a brush using her mouth (she can no longer speak because her tongue has been cut off) to describe what has happened to her family are definitely worthy of another “Good Lord” or two.

It’s this poor woman’s suffering that helps convince aging samurai and man of justice and decency Shimada Shinzaemon (Yakusho Koji) to agree to a proposal by Sir Doi Toshitsura (Hira Mikijiro) to discreetly assassinate Lord Naritsugu before he becomes an advisor to the shogun and does even more damage.

What Sir Doi and his peers fear is that Lord Naritsugu’s excesses will cause turmoil in the country, which has been enjoying years of peace–and yet maybe turmoil is what everyone secretly wishes for. Lord Naritsugu definitely wants it since it would relieve his boredom. And many of the samurai in the movie express their own disenchantment with their way of life. The samurai are no longer known as warriors, they’ve become lackeys of the government, perceived as weak and useless compared to their wartime predecessors. Shinzaemon’s own nephew, Shinrokuro (bedroom-eyed sexy creature Yamada Takayuki), for example, considers being a samurai a burden, choosing to spend most of his time at tea houses getting drunk with geishas.

Lord Naritsugu, following the example of villains who always speak the truth, manages to coldly point out the crux of the samurai problem when one of them tries to stop him from murdering a family: the samurai are little more than servants whose code of loyalty has been twisted to blindly obey their master, even ones as awful as Lord Naritsugu. “Dying for one’s master is the way of the samurai. Dying for one’s husband is the way of women.”

Lord Naritsugu equates samurai–despite being paragons of masculinity and skill–with women for a reason. Neither has a choice but to serve, suffer, and die because the system they operate in doesn’t give them a choice. Lord Naritsugu’s samurai bodyguard, Kitou Hanbei (Ichimura Masachika), himself laments, “A samurai leads a helpless life.”

In some ways, the mutilated peasant woman is a symbol of samurai honour: torn apart and abused for the amusement of those in power, then cast aside when they’re no longer useful. It’s also the words that the peasant woman’s written–“Total massacre”–that he unfurls at the village where Shinzaemon and his fellow assassins ambush Lord Naritsugu and his guards.

Like the peasant woman, the only honourable way out of a miserable life is death (in the samurai’s case, preferably a good one). After he meets her, Shinzaemon gets tears in his eyes when he realizes that he now has his chance to avenge not only the peasant woman by killing Lord Naritsugu but also gain an honourable death with a suicide mission.

While one of the other samurai that Shinzaemon recruits for this mission is doing it for practical reasons (he needs money), the others have a similar glorious death wish. As with the other stories in this series, 13 Assassins proposes that mainstream society has no room for the kind of violent masculinity that is required from tough guys, gangsters, and delinquents. Miike himself said: “As men, we want to see some kind of ideal of masculinity, even though modern society might restrict us in our own lives.” I should note here that Miike is fantastic at casting actors who embody this ideal masculinity; this film is full of single malt whiskey voices and utterly manly actors whose age only adds to their coolness.

Sigmund Freud would agree with Miike about the clash between society and masculine aggression. In Civilization and Its Discontents, he wrote that civilization has no room for the kind of self-destructive aggression that he termed the death drive. The samurai way of life, born from the death drive and years of war, can’t be sustained when there is no further need for violence. The samurai mostly recognize this, and even Lord Naritsugu sees its unsustainability, even as he openly plans to cause war to bring it back again.

By the end of the movie’s infamous, breathtaking, thrilling, and multiple “Good Lord”-inducing forty-five minute bloodbath, Shinzaemon and his assassins have managed to completely kill over 200 soldiers and samurai, and only Lord Naritsugu is left alive.

Lord Naritsugu, being that he’s been spoiled and deferred to his whole life, is offended when Shinzaemon calls him a “decorative man” with a “decorative weapon” that’s only for show and useless for anything truly masculine. Lord Naritsugu only enjoys killing and fighting when it’s others who are doing the dying and suffering, when to be a real man, you have to embrace pain and death. As Shinzaemon tells his fellow assassins early on: “He who values his life dies a dog’s death.”

In a lot of ways, Lord Naritsugu is like those guys who fetishize samurai and other honour culture warriors, thinking that they’re men just like them. Except, like Lord Naritsugu, despite making edgy pronouncements about wishing to be beheaded to see what it feels like, they’re the ones who end up shocked to find themselves crawling in the mud, terrified of dying because they haven’t considered the gravity or the pain of it. With that said, Lord Naritsugu at least thanks Shinzaemon for making his last day on earth exciting, which goes to show just how removed from real life he is.

I wonder if the movie is implying that only in times of peace do men like Lord Naritsugu flourish–not necessarily psychopaths, but just decorative men who take a stab (hah) at being real men but are really just embodying it in the shallowest way possible, perhaps through appearance or hobbies. Wartime culls the true men from the decorative men, after all. You could also say that Lord Naritsugu is what happens to men who don’t have healthy or appropriate channels for their masculine aggression. And since many of us in the developed (and even some developing) world are living in a time of peace, way past honour culture problems, we see more men like Lord Naritsugu than true men like Shinzaemon. All you have to do is look at comments sections online.

To go back to Freud, he wrote that the death drive must be repressed in modern society to keep civilization from falling apart. So inevitably, the question is: what happens to real men? The ones who are, in Miike’s words, an “ideal of masculinity”? What place do they have? The stories I’ve been looking at in this series have all tried to answer this, but inevitably, it seems like this type of person really just has no choice but to die a violent death in order to be true to himself.

The other option, as Shinrokuro and the final assassin Koyata (Iseya Yusuke), a former bandit turned hunter who probably comes back as a ghost in the end or is a forest spirit in the first place, end up choosing as the token survivors, is to go back to their lives with women–but not just any women, women who are also outcast from mainstream society in a way. For Shinrokuro, it’s his geisha lover Tsuya, and for Koyata, it’s the adulterous wife of his bandit leader, Upashi.

I would like to emphasize here that they are both played by the same actor, Fukiishi Kazue, which I think is very significant. Tsuya/Upashi is obviously linked to sex and eroticism, and her femininity stands as a direct contrast to masculine aggression. She is the symbol of the life drive, which Freud considered the opposite of the death drive, and the fact that the two survivors (assuming Koyata isn’t a ghost) are her lovers means that they have survived because they’ve embraced the life drive in some form.

The last scene of the movie is of Tsuya welcoming Shinrokuro home, right after we’re told that the Tokugawa shogunate ended after twenty-three years. Japan then entered the Meiji period, during which it moved away from feudalism and modernized, removing the need for samurai entirely and subsuming the death drive. Although the film begins with a samurai committing seppuku, the ultimate act of honour, we end with Tsuya happy that Shinrokuro is alive. Eros prevails.

With that said, Shinrokuro seemed pretty happy to be going home to Tsuya, so perhaps the movie isn’t just about how masculinity needs to end in death, but also about how, after it’s given a chance to fully express itself, it can be integrated into society.